You are here

“Proust’s political and literary activities are indissociable”

Proust was a great novelist, but he was more than a writer. In what way was he also an engaged intellectual?

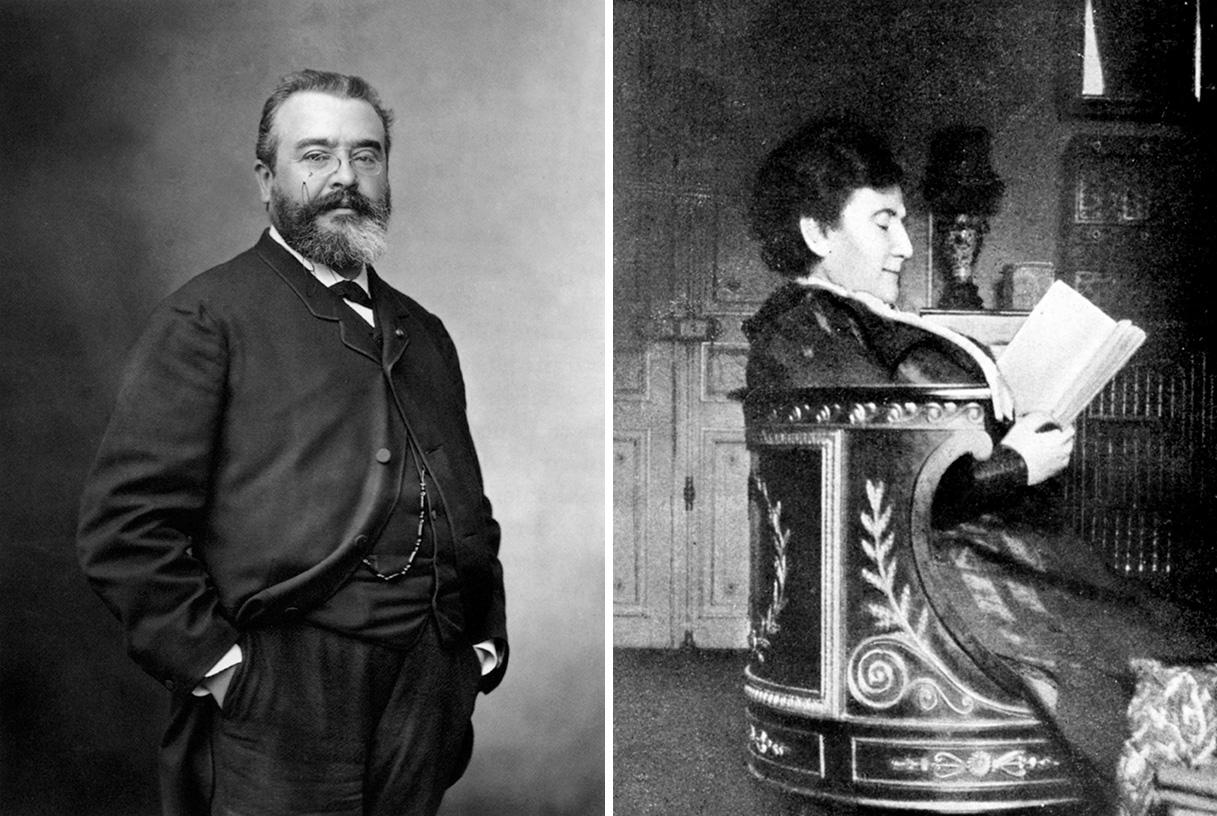

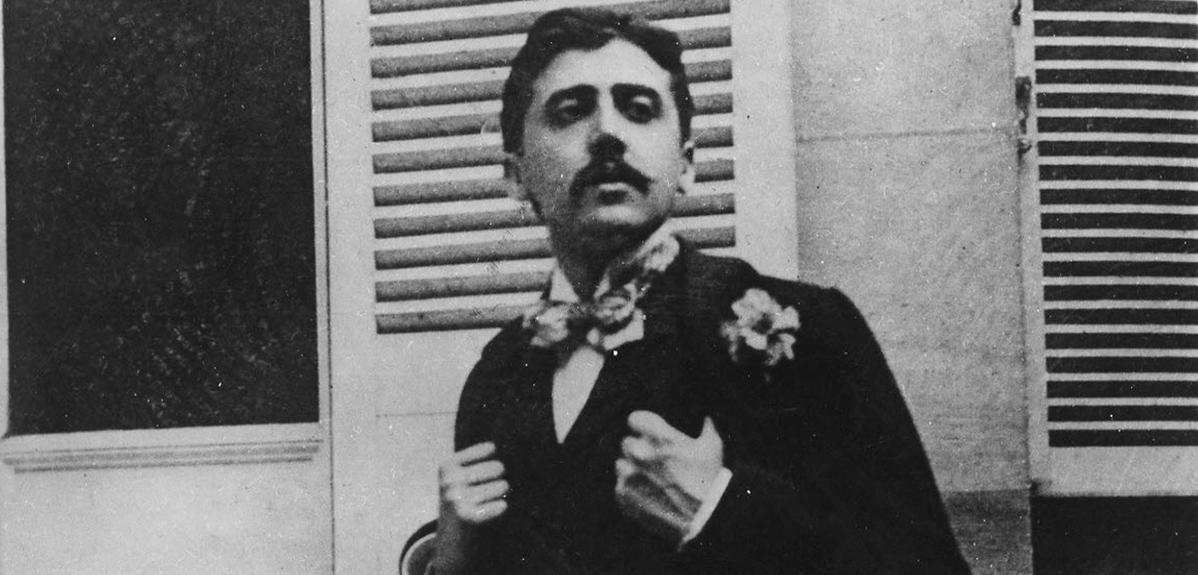

Anne Simon:1 It’s difficult to make a clear distinction between the two, because Proust’s political activity is indissociable from his literary activity, interrupted only on a few rare occasions in his life. At the time of the Dreyfus affair, for example, which began barely a century after the French Revolution had granted citizenship rights to Jews, he was still a young man in his twenties, unknown to the general public. In 1898 he signed and helped disseminate the famous Manifeste des Intellectuels (Intellectuals’ Manifesto) in support of Captain Dreyfus, who was unjustly accused of treason because he was Jewish, and of the French writer Émile Zola, who had just published J’accuse…!, a pamphlet in favour of the high-ranking officer in the former French daily L’Aurore. When Colonel Picquart was in turn imprisoned for having defended the captain’s innocence, Proust sent him a copy of his first book, Pleasures and Days. It must have taken tremendous faith in literature for a young author to offer a collection of short stories with such an ill-fitting title to an imprisoned military officer! It’s both naïve and touching.

This period corresponds to Jean Santeuil, a colossal fiction project that remained in manuscript form, was published only after Proust’s death, and is now being studied by the Proust team2 at the ITEM.3 The young protagonist is of course in many ways an alter ego of the author: he attends the trials, describes the atmosphere and the issues, and praises the arguments of Dreyfus’s defenders. As a testimony, an homage and an expression of his deep “anger”, the aborted novel Jean Santeuil can be seen today as a “black book” on the Dreyfus affair.

An important part of the manuscript of Jean Santeuil is dedicated to the premises of the Armenian genocide…

A. S.: In the book, Proust describes how he was moved by a speech delivered by Jean Jaurès in Parliament in 1896: driven by “an inner voice”, the politician denounced the failure of France and Europe to take action against the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, who had ordered horrific massacres of Armenians. The very idea of a unified Europe is presented as being undermined by cowardice or pragmatism in relation to the ascendancy of major powers over weakened regions, and populations denied the right to a homeland. This was a question that would haunt the entire 20th century, up to the present day. Proust understood that a Europe devoid of “responsibility” and “valiant” leaders was a land of darkness. But he never completed the novel for purely literary reasons: his text seems to be split in two, with one sensationally political facet and the other more fin de siècle and already “Proustian” – a recounting of childhood, emotional stirrings, amazement at the wonders of nature, first forays into society… It was an unsuccessful attempt at interweaving politics and everyday life.

In your opinion, what is the reason for Proust’s sensitivity to discrimination?

A. S.: Proust had personally experienced anti-Semitism. His mother was Jewish, from a family that was highly active in institutions representative of Judaism, like the Israelite Central Consistory of France and the Universal Israelite Alliance. On the other “side”, Proust’s father was from a Catholic family, some of whose members were anti-Semitic. In addition, Proust was homosexual, a “vice” that in those days aroused “opprobrium” and “ostracism”, as he describes in Sodom and Gomorrah. It is difficult today to appreciate the courage that it took for him to keep such a title for a volume of Search (In Search of Lost Time, 1913-1927, seven volumes). Belonging to two minorities, Proust was subjected to a number of discriminations that exacerbated one another and made him attentive to various forms of injustice (he defended the “massacred churches”, living places embodying a memory, when they were threatened by the law on the separation of church and state in 1905). Françoise Gaillard (senior lecturer at Université Paris VII) analyses an “ideologeme”4 that was quite common in Proust’s day – a cliché based on a set of collective beliefs combining, in this case, anti-Semitism and homophobia. Jewish men were considered to be decadent, thus feminine, and thus homosexual – and vice versa! In Search, Proust reclaims this syllogism, examines it from within and studies its social and psychological effects: he mentions “two doomed races”, that of the Jews and that of the “tantes” (“sissies”) or “invertis” (“inverts”), a term that he favoured, unlike André Gide, who strongly objected to the idea of “female-men”. The fact that this controversy even arose between them, in private, shows how much they had to contend with society’s taboos.

How do you explain the anti-Semitic and homophobic stereotypes that can occasionally be found in Search?

A. S.: By the ambivalence due to the appropriation of the imposed stigma, but also humour, as a way of distancing himself from it, and lastly irony, which assimilates a statement in order to satirise it from within. The narrator, Catholic and heterosexual, serves as an avatar to enable this distancing, as well as the encrypted references mentioned by the novelist Nathalie Azoulai (Prix Médicis 2015). These references are related to the importance of Judaism within Catholicism (the tapestries depicting the crowning of Esther at the back of the church in the village of Combray), but also to the strategies for accepting it or not. At the time, many Jews – or “Israelites” – longed for assimilation, while others, traditionalist or Zionist, embraced their singularity.

In his formal social relations, and even friendships, Proust sometimes rubbed shoulders with members of the extreme right. Luc Fraisse (professor of French literature at Université de Strasbourg) recalls that the novelist had been criticised, in the uproar surrounding his winning of the Goncourt Prize in 1919, for having the backing of Action Française5 and Léon Daudet, a talented but anti-Semitic journalist. If Proust had indeed accepted such support (which he attempted to downplay by pointing to the fact that he had been a keen defender of Dreyfus), it was out of concern for the legacy of his work, and the desire to be seen as a French author.

As Marisa Verna (professor of French literature at the UCSC catholic university of Milan) shows in “Style and Politics”,6 Frenchness for Proust meant “tackling the language”, making it “a foreign tongue” suited to saying something new. It is thus best to avoid projecting political dichotomies on the past or making hasty judgments, from today’s perspective, on the unease, compromises and strategies for social integration that an “Israelite” or “invert” could have dealt with in those days. Concerning the bourgeoisie and aristocracy of his time, Proust offers a genuine depiction of their so-called “wit”, their hypocrisy and the humiliations that they inflict. Proust the socialite was above all a magnificent satirist.

Did his vision of sexuality have a political dimension?

A. S.: There is a whole existential dimension of love in Proust’s work. In his hands it becomes a sort of illusion of the self, but his writing also shows, according to Annamaria Contini (professor of aesthetics at the Italian university of Modena and Reggio Emilia), that intimate relations are to be associated with social7 – and, I dare say, venal violence. For example, the narrator of Search supports a young woman, Albertine, who can exert reciprocal power over him solely because her potential attraction to women makes him jealous. In early 20th-century society, with its class divisions, desire also became a factor for social mixing. Homosexuals, in particular, were obliged to socialise beyond their circle. This reminds me of a very funny scene in the beginning of Sodom and Gomorrah: the Baron de Charlus, who is obsessed with his aristocratic genealogy, falls madly in love with a tailor who “loves only old gentlemen”. The narrator compares the baron to a bumblebee trying to pollinate the only species of orchid that suits it! Desire thus engenders social intermingling, against a Darwinian background with a subversive facet that was not lost on Proust.

Would you say that he tried to take an apolitical view of human relations?

A. S.: I don’t think so, because Proust always depicts situations and events in history, and the fragility of collective memory. The First World War induced him to rework and develop his novel: he described the war’s social effects and moved Combray, the childhood village, from Chartres to Reims, locating it in a war zone so that it could end up being destroyed at the end of the novel – an image of times lost and oblivion. This is also why his writing is sometimes very crude, as when he recounts a flogging scene in a house of ill repute: making his protagonist a voyeur or gossip monger is a novelistic strategy that offers the reader a window onto otherwise inaccessible worlds. He also takes us to breakfast with Madame Verdurin, who is upset by the sinking of the Lusitania – and finds solace by dunking her croissant (a luxury during the war) in her white coffee! Proust did not want to write “genre” novels, falling into the category of “patriotic” or “popular” art, for example, because they reduce history to a mere backdrop, overlooking each individual’s evolutions and contradictions. He engaged in politics by showing how his characters embody a complex period and specific backgrounds they cannot be dissociated from.

How does he analyse the economic and social relations of his time?

A. S.: Proust, the son of a prominent professor of medicine and a mother from an influential Jewish family, understood that social circles are less impenetrable than they seem, and that people are ambivalent. Gilberte Swann, who renounces her Jewish name to take that of her stepfather, the Comte de Forcheville, ends up marrying an aristocrat from a long family line, becoming a caricature of snobbery and self-deprecation. The obnoxious Madame Verdurin, who runs a bourgeois salon called the “little clan”, is also a major patron of the arts and ultimately becomes the Princess of Guermantes. The world of domestic servants is sometimes linked to the Ancien Régime and sometimes cast in the light of its modern evolutions: the housekeeper Françoise loses her old dialect, makes herself indispensable and, as Brigitte Mahuzier (professor of French language, civilisation and literature at Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania, USA) points out, wields a certain influence over her employers.8 The working class does not feature much in Proust’s novel, although he does mention, in In Search of Lost Time, that the members of the Jockey Club are “illiterates” less likely to understand his work than the “electrical workers” of the French CGT trade-union!

Does he foresee the advent of a less divisive society?

A. S.: Not specifically, but he was aware that his world was changing. In a delightful passage from In The Shadow of Young Girls in Flower, the narrator is on holiday with his grandmother at the Grand-Hôtel in Balbec, a seaside resort. The other guests include an aristocrat of long lineage, a high-ranking legal official, a minor country squire, etc. All are brought together (trying not to mingle) at dinnertime. The town’s fishermen, labourers and petty bourgeois crowd around the bay window to marvel at this exotic fauna. One of the onlookers is a writer! Proust describes him as a “keen observer of human ichthyology” who takes pleasure in “classifying” the “old monstrosities”, i.e. the aristocrats, by breed, as well as by innate and acquired characteristics”. I love the idea of this social fish stocking, transforming the rich and powerful into “marvellous creatures”: there was a crack in the social “aquarium” of the early 20th century, which was threatening to burst – this was the time of the Russian Revolutions of 1905 and 1917. Not that Proust supported them – far from it – but his world was teetering, and his witnessing that is a key aspect of his work.

For further reading: Proust Politique. De l’Europe du Goncourt 1919 à l’Europe de 2019 (“Political Proust. From the Europe of Goncourt 1919 to the Europe of 2019”), Quaderni Proustiani, 14, 2020, edited by Anne Simon, Davide Vago, Marisa Verna and Ilaria Vidotto.

To find out more, see the Pôle Proust research blog: https://poleproust.hypotheses.org/

- 1. CNRS senior researcher at the CRAL centre for art and languages (CNRS / EHESS), head of the Pôle Proust network and co-editor of the report on the “Proust Politique” symposium held at the UCSC catholic university of Milan, Italy, 9-10 May, 2019. (https://poleproust.hypotheses.org/3411).

- 2. (http://www.item.ens.fr/proust/)

- 3. Institut des Textes et Manuscrits modernes (CNRS / ENS Paris).

- 4. http://quaderniproustiani.padovauniversitypress.it/system/files/papers/Q...

- 5. http://quaderniproustiani.padovauniversitypress.it/system/files/papers/Q...

- 6. http://quaderniproustiani.padovauniversitypress.it/system/files/papers/Q...

- 7. https://quaderniproustiani.padovauniversitypress.it/system/files/papers/...

- 8. http://quaderniproustiani.padovauniversitypress.it/system/files/papers/Q...

Explore more

Author

Fabien Trécourt graduated from the Lille School of Journalism. He currently works in France for both specialized and mainstream media, including Sciences humaines, Le Monde des religions, Ça m’intéresse, Histoire or Management.