You are here

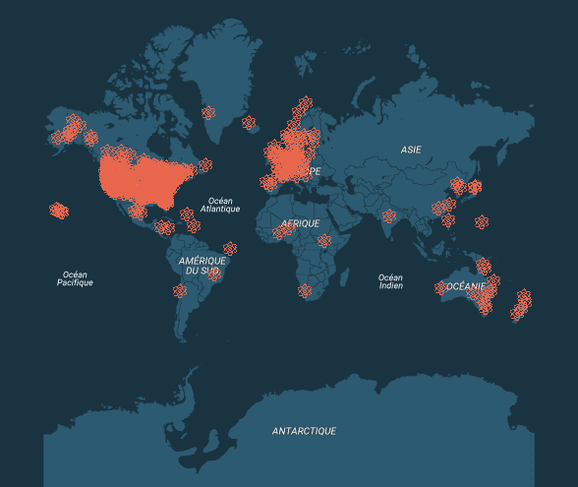

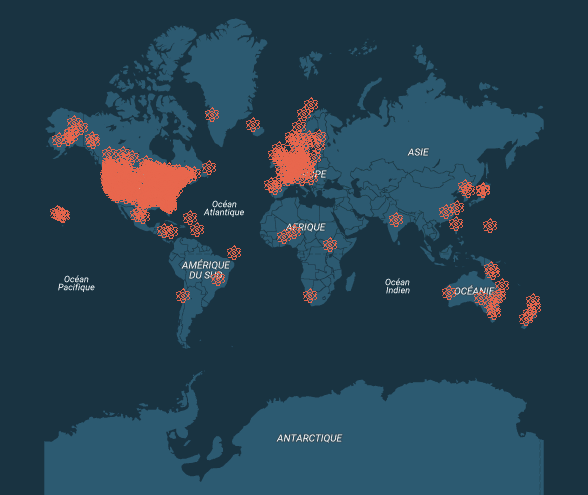

Why the World will be Marching for Science

“There needs to be a Scientists' March on Washington.” This comment was posted on Reddit, an online forum, on January 20, 2017. It was one day before the Women’s March, which would become one of the largest single-day demonstrations in US history. A week later, newly-created Facebook and twitter handles had attracted over one million followers. The March for Science was born. What had started as a knee-jerk reaction to the new US administration's possible changes in science policy, became something much bigger, a grassroots movement to defend and promote the role of science in society. The movement’s broad appeal caught on, and although the main event will take place on the National Mall in Washington DC, many satellite marches in the US and across the world are now scheduled for Earth Day, April 22nd, 2017.

A change of climate

One of the very first members of this online community was Valorie Aquino, a PhD candidate in anthropology from the University of New Mexico (US). Today, she is one of three co-chairs of the March for Science's committee1 and admits that she has been overwhelmed by the response, her schedule now overrun with meetings and press briefings. "What is incredible is that this is an all-volunteer effort spanning the globe," says Aquino, who will be marching In DC. "Most of us had never met before, so we had to coordinate effectively with people of widely-varying backgrounds and across multiple time zones." The first draft of the administration's proposed budget—released in March—that proposed cuts to a number of programs ranging from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which operates Earth-monitoring satellites to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which enforces national standards in terms of environmental protection and human health seems to have only reinforced the marchers' determination. "These cuts would lead to a disastrous freeze of scientific and technological research and innovation in the US. It overlooks the critical role that this research plays in our lives, our communities, and the economy," she says, not hiding her disappointment. Yet what this march is not, is a protest against the administration.

Beyond the partisan divide

The organizers have worked very hard to take political partisanship out of the equation. On their official website, participants will find the movement's core principles, ranging from evidence-based policy to diversity and inclusion in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) education or the importance of research funding. But their stated objectives are much broader: to put a human face on scientists, make their work more accessible to the general public and explain how their findings improve the daily lives of millions. "As an example, the DC event will have 18 teach-in sessions (6 tents of 3 one-hour sessions) at the National Mall, which will not only host engaging and educational activities, but will also invite participants to take part in tangible actions in the following days and months,” says Aquino, adding that the March now has the support of many of the country's scientific institutions, associations and universities.2

One of the first to back the movement was the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), the world's largest general science membership organization and publisher of the Science family of journals. "We recognized very early on that this was a rare opportunity to communicate the broader message of why we need science," enthuses AAAS CEO Rush Holt. "Within days, this march became the talk around the labs, universities and research centers, and groups the world over joined the conversation. For the first time in years, scientists began talking about getting out of their laboratory, and taking to the street," Holt continues. He is aware of the issues at stake. An executive order barring citizens of several countries from entering the US was imposed just weeks before the association's annual international meeting in Boston on February 22nd. "If we want science to thrive, we must defend the conditions where it will thrive. If immigration orders interfere with the ability of scientists to collaborate, that is detrimental to science, which in turn hinder people's quality of life."

Restoring the facts

Although funding is also on the table, Holt praises the organizers for putting less emphasis on it. "We don't want a non-scientific public to think that this march is about scientists looking after their own interests," he says.

For him, there is a much more clear and present danger: "Even more than restrictions on funding, or on travel, a very worrying trend has emerged in recent years: Some members of the public have decided that evidence is optional. That opinions are as good as facts," he continues. "Yet scientists have built their careers on a reverence for evidence and a belief that by passing evidence through a process of verification, we gain knowledge that can improve the human condition. Scientifically-vetted evidence is not the same as opinion. Policies regarding climate change or vaccinations, or any issue involving public health and welfare, should be based on scientifically-vetted evidence. Yet this is not always the case. Policies are increasingly implemented not only in the absence of evidence, but with the deliberate rejection of evidence. And that is very serious," he explains.

A call heard around the world

The deliberate erosion of scientific evidence is not unique to the US, which may explain the overwhelming support this march has received in other countries. “So-called 'alt-facts' are increasingly accepted as a foundation of social discourse worldwide, which, eventually, poses a direct threat to science,” says Tanja Gabriele Baudson,3 a national coordinator of Science March Germany. “Once scientific facts are presented as merely one out of many alternative opinions, they lose their significance, and science loses its purpose," she adds. In Germany, marches are already planned in 20 cities, and several institutions—some of them part of the Alliance of the German Research Organizations—have officially backed it, alongside five Nobel Prize winners.4 “In Germany, our main concerns are not about research funding or environmental policies," explains Georg Scholl, a spokesperson for the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. "The reason why our institution has backed this march is to raise awareness for science in general and fight its denial, like the anti-vaccination movement which continues to try to gain support in the country.” Much like in the US, France, or the UK, discredited theories linking the MMR vaccine to autism have made some Germans skeptical about immunization.

In France, where marches are scheduled in 20 cities,5 it all began with a tribune in the daily newspaper Le Monde,6 signed by a handful of researchers. "We were quite concerned by what was happening in the US, but we also have issues in France," explains co-signer Arnaud Saint-Martin, a CNRS researcher and sociologist at the University of Versailles-Saint-Quentin and a member of the French March's national organizing committee. "We’re not sheltered from possible changes in policies. We also believe that putting too much emphasis on innovation can stifle basic research," he adds. And although it is a grassroots citizen's initiative, all major French science institutions, including the CNRS, CEA, Inserm and others, were quick to back it.7 CNRS President Alain Fuchs believes this is a worthwile initiative. "The mere prospect of hindering scientists’ ability to conduct research and disseminate their results goes against the interests of nations. Yet it seems that this is the situation we will soon be faced with. This is why I fully support the March for Science initiated by our American colleagues to defend the notion that knowledge and scientific progress are the cornerstone of our democratic societies," he emphasises.

Scientists are aware that they need to fight disinformation with the values that give research its strength. "It all rests on independence of research, academic freedom and scientific autonomy. And France, compared with other places, is quite lucky in this regard, but we should not let our guard down," adds Saint-Martin, who, like his US colleagues is intent on extending the march to the general public. “Our main objective is also to bring everyone together. In the organizational committees, we have students, teachers from primary and secondary school, people generally interested in science... we want this to be a citizen’s march," he concludes. A somewhat delicate exercise, considering the march will take place one day before the first round of the French presidential elections.

A global celebration of science

The country that best captures the spirit of the DC march seems to be the UK, which is keen on making this event a great celebration of science. "The situations in the US and in our country are very different. In the UK, there has been a significant allocation of new funds for scientific endeavor and the climate is pro science, yet we are still concerned about scientists' ability to continue working collaboratively across borders in light of Brexit. How is that going to play out and impact researchers' capacity to do their work? Science is a global undertaking that requires collaborative work," says London March co-organizer Marsha Nicholson, who, despite 20 years of experience managing people and events for NGOs, is new to organizing on such a scale. "It started out very organically as a march in solidarity," she explains, hoping that people will join the many marches organized throughout the country, from Bristol to London, as a celebration of science.8

Reaching out

One objective that stands out in all the planned marches from DC to Berlin, is that a link needs to be strengthened, and sometimes restored between science and the general public. "People can feel alienated from science," Holt notes. "Some may think that scientists are just imposing their conclusions and their gut reaction is to reject that. I think the March for Science is an opportunity to address this. To remind people that science is not primarily for scientists, but for the people. The public has the right and the duty to always ask 'what is the evidence?,' whatever the issue. And scientists have an obligation to make the evidence understandable to the public." Back in Germany, Scholl believes that this central issue may prompt the scientific community to reflect upon itself. "One of the problems," he says, is that “it is easier for the public to access 'misinformation' on social media than scientific evidence in publications like Nature. This may invite us to reflect on how we share scientific knowledge in the first place.”

A global reset

Among those who have advocated a different approach is Robert Young. In February, this climate scientist9 argued in a very controversial opinion piece that the Science March risked alienating the very audience they were trying to reach. He believes that a considerable segment of the population would only see it as a strong rejection of the new administration's positions, creating an even greater divide between so-called scientific "elites" and the general public. "The US has never been this divided, and the way the media and Internet work ensures that people with different opinions can avoid talking to one another entirely," Young says. For him, the real solution is more local outreach. The lesson he has learned from the past election is that Donald Trump "was able to connect on a personal level with a large section of the country, rural America for example. The scientific community to some degree needs to do the same. We have to meet people where they live and show them that we're just like them," he adds. Young, whose grandfather worked on an assembly line for General Motors in Michigan and whose wife's family were employed in cotton mills in South Carolina believes the thousands of scientists who have similar stories and upbringing could become great science ambassadors. "But it can't happen overnight and it can't happen on CNN," he admits, acknowledging that there are better ways of reaching these communities. One such example is AM radio shows, where he makes regular appearances to address climate change. "I'll sometimes get insulted because I'm a climate scientist, but I may also get a quiet email from a skeptic asking me a couple of questions about the science," he says. "Most scientists mention polar bears when talking about climate change. But we have to make it more personal. In eastern North Carolina, for example, we need to do a better job of explaining that rising sea levels will make it more difficult to plant tobacco over the coming decade in the very low elevation areas near the sea. The fields don't drain anymore, and that's a tangible impact of climate change. We must get better at telling these stories," he concludes, adding that he will probably join the march in Vienna (Austria), where he will be attending a conference.

- 1. https://www.marchforscience.com/national-committee-1/

- 2. Scientific institutions in the US backing the march: http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/02/will-they-or-won-t-they-what-scie...

- 3. Visiting professor of Methods in Empirical Educational Sciences at Dortmund University.

- 4. German institutions backing the march: http://marchforscience.de/unterstuetzer/

- 5. French cities with organized marches: http://www.marchepourlessciences.fr/sample-page/les-marches-en-france/

- 6. http://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2017/02/15/marchons-le-22-avril-pour...

- 7. http://www2.cnrs.fr/presse/communique/4891.htm

- 8. Marches in the uk :https://sciencemarch.london/satellite-marches/

- 9. Director, Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines, Professor, Coastal Geology at Western Carolina University.