You are here

Who Built the Eiffel Tower?

"Gustave Eiffel was the perfect example of a 19th century engineer: inventive and daring,” says Lemoine, who is himself an engineer, architect, and specialist in the history of architecture at the CNRS.1 “Eiffel graduated from the Central School of Arts and Manufactures2 in 1855, a major time of growth, stemming from several concurrent factors: the rapid economic expansion of Europe, at the height of its industrial revolution; the appearance of a new material, rolled iron, which was lighter and cheaper than stone; and decisive progress in mechanics.”

A globe-trotting engineer

In this favorable context, Eiffel became an internationally renowned structural engineer not only through the design of the world-famous Eiffel Tower, but also as a result of the 300 or so structures he built all over the world, including bridges, viaducts, roof structures, churches, and stations. His contributions to scientific research shouldn't be forgotten either.

Eiffel had all the makings of a great engineer. Encouraged by his success in a steel construction company, where he headed in particular the construction site for the Bordeaux railway bridge, he set up his very own company at the age of 32. He surrounded himself with efficient technicians and inventive engineers, and started establishing lasting partnerships with investors. At the time, structural engineering was increasingly in demand. Railways were expanding throughout Europe, and stations, bridges, and public buildings were changing the landscape. “Iron enabled you to build fast: The parts were mass-produced in workshops, and they could be sent back to the factory in case of problems. On site, all you had to do was to assemble them with rivets,” Lemoine explains. It was not unlike a Meccano model construction kit, but on a grand scale, in sharp contrast to traditional building sites, where stones had to be cut and recut on the construction site to fit—a process that could drag on for years. Furthermore, the scientific laws that explained how materials deformed due to the stresses and shapes of structures, discovered by Claude-Louis Navier in 1821, were now commonly being applied.

“The shapes of beams and buildings were designed so as to optimize their resistance, while at the same time making them lighter,” Lemoine explains. Structures made increasing use of openwork. And you could build them bigger and taller without any fear of them collapsing under their own weight, or breaking in high winds. Among the new generation of engineers, Eiffel won many contracts due to technical innovations that could cut costs. “For instance, for the Maria Pia Bridge in Porto (Portugal), he suggested using cables to hold up the two arches that met to form the bridge,” adds Lemoine. As a result, there was no need to put up expensive scaffolding in the river.

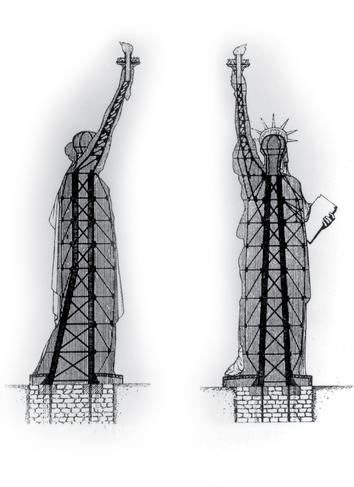

The Garabit viaduct in France, the internal structure of the Statue of Liberty in New York... no sooner had Eiffel finished one job that he moved on to another. And he was soon to embark on his life's greatest achievement. “For the Universal Exhibition of 1889, which marked the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution, France wanted to pull out all the stops,” says Lemoine.

A tower to rise above the others

The idea of a tower was being mooted. It would be taller than any structure ever built, even outstripping the Washington Monument, which was 169 meters tall. Two engineers from the Eiffel company, Émile Nouguier and Maurice Koechlin, designed a 300 meter-high tower. Although Eiffel initially showed little interest, he was won over by the embellishments added by the architect Stephen Sauvestre, and registered a patent.3

The tower won one of the four prizes in the exhibition's architecture competition. Publicity in the press and public meetings helped to make Eiffel's project increasingly credible, and an agreement with the government was finally signed. Funded partly by Eiffel's own money, the project would finally get off the ground. Work began in January 1887 to be completed a mere 26 months later. The tower was to amaze two million visitors during the six months the exhibition was open. “It was supposed to be torn down after 20 years, when the free lease granted by the city of Paris expired.

But Eiffel saved it by demonstrating its scientific importance as a site for a radio antenna, and for carrying out experiments, in particular in aerodynamics,” adds Lemoine. Eiffel retired from business at the age of 61, but continued a career as a researcher until the ripe old age of 88.

This article originally appeared in CNRS International Magazine issue 28

Explore more

Coulisses

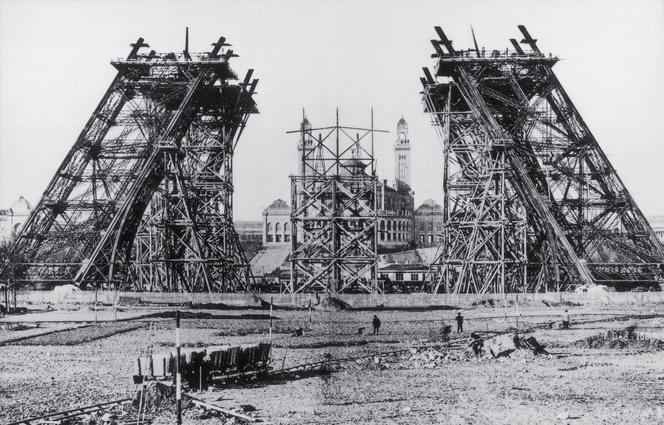

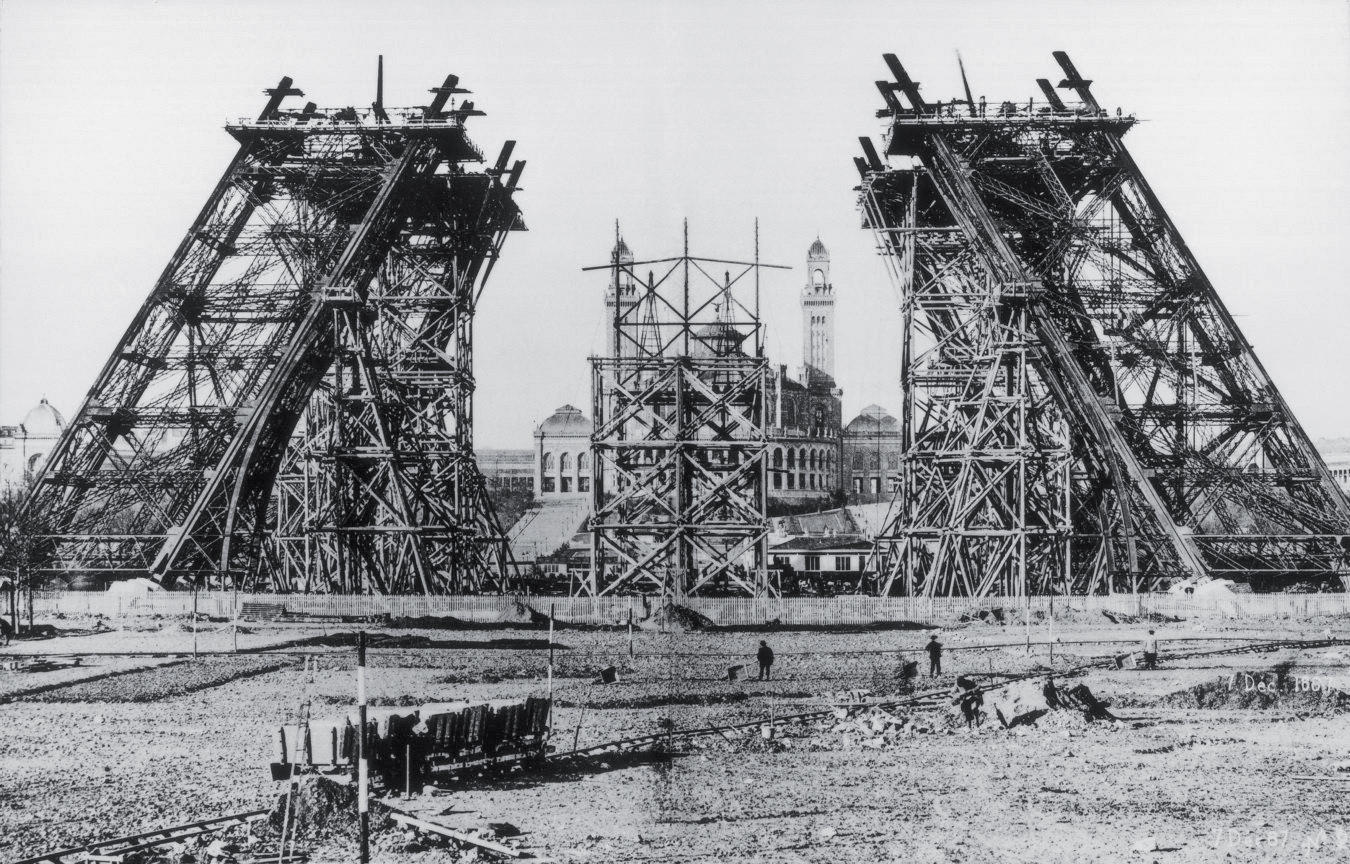

December 1887: Before the first level was completed, making the whole structure stable, the four legs were held up by scaffolding. Eiffel had the idea of placing boxes filled with sand inside them, as was done in Ancient Egypt. Removing a little of the sand slightly lowered an entire leg, and above all, enabled all four legs to be adjusted to the same height. Had they been just a few millimeters off, the rivets would not have fit in the holes of the plates that were then assembled.

Author

Science journalist, author of chilren's literature, and collections director for over 15 years, Charline Zeitoun is currently Sections editor at CNRS Lejournal/News. Her subjects of choice revolve around societal issues, especially when they interesect with other scientific disciplines. She was an editor at Science & Vie Junior and Ciel & Espace, then...