You are here

Making humans more creative

This interview was initially published in issue 14 of the journal Carnets de science

Your personal page states that your research is aimed at developing creative artificial intelligence. What does this involve?

Marie-Paule Cani1: It involves making humans more creative thanks to intelligent models. I would like users to be able to materialise what they have in mind with the help of systems that perform repetitive and tedious tasks. This is by no means artificial intelligence (AI) that creates in your stead. I have been fighting against this from the beginning. When people think of creative AI, they think about Dall-E or ChatGPT, which can produce something based on a sentence.

Using these applications means cutting and pasting what already exists rather than taking the trouble to reflect on what we truly want. This is not at all the direction of my research. My goal is to conceive intelligent systems that help the user, a little like an assistant hands a surgeon the right instrument at the right time.

Creative tasks are some of the most interesting on Earth, so why entrust them to a machine? We should instead delegate tedious chores, those that we do not like doing.

How do you help designers focus on creative tasks?

M.-P. C.: By giving them tools to work with, all while remaining within the surge of creation. Instead of opening a menu and then a submenu to edit a particular parameter, I want users to create through gestures. Here is an example I often give: let’s say we’re making a table with plates, cutlery, and glasses. Now, I want to be able to lengthen that table with a single gesture. The intelligent system must recognise that there are repetitive details, such as the dishes and cutlery, which must be duplicated rather than stretched. I can then take over to modify and refine the details, without having to change the rest. The idea is to interpret the creative gestures of users so that they do not have to contend with the complexity of computer models.

The developers of video games and animated films use the tools you design. How do you identify their needs?

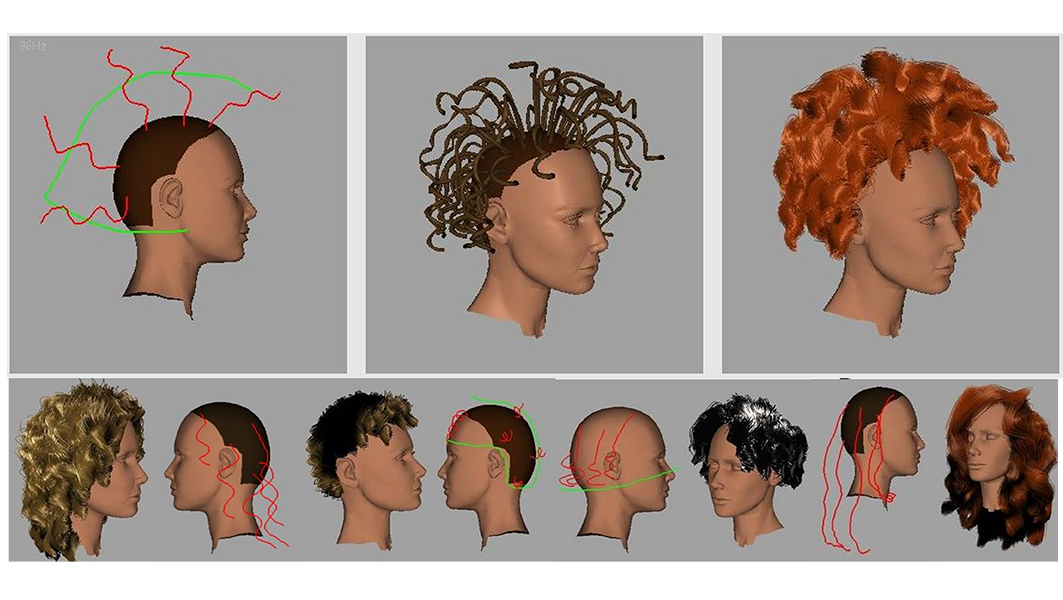

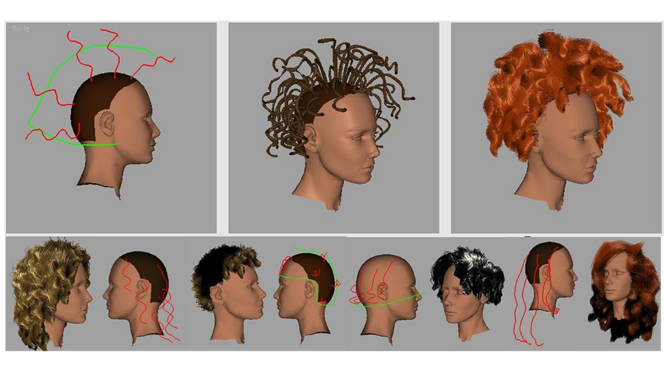

M.-P. C.: It’s by watching artists work, by asking them what they spend the most time on, what bothers them, that we find methods for simplifying their task. For example, during my sabbatical in New Zealand in 2007, I was invited to Weta Digital2, the special effects studio founded by the film director Peter Jackson. They told me that for the film King Kong, which they had just finished, a computer graphics designer had to attach the gorilla’s virtual tufts of hair by hand, and then comb them so the fur would look natural and a little tangled. It was a very repetitive task that took him days to perform. It would be simpler for the user to create a small example of ruffled fur and, in a single stroke, extend it across the entire surface of the virtual model.

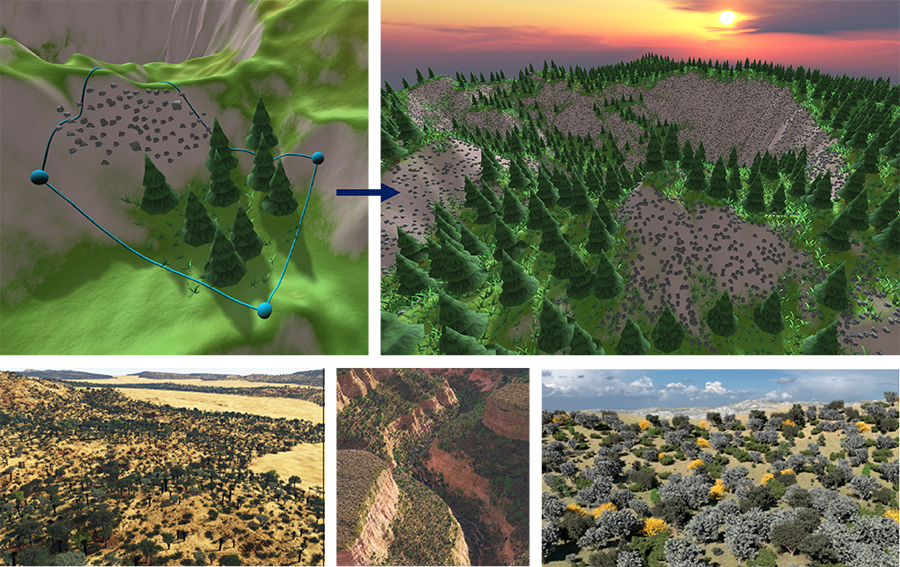

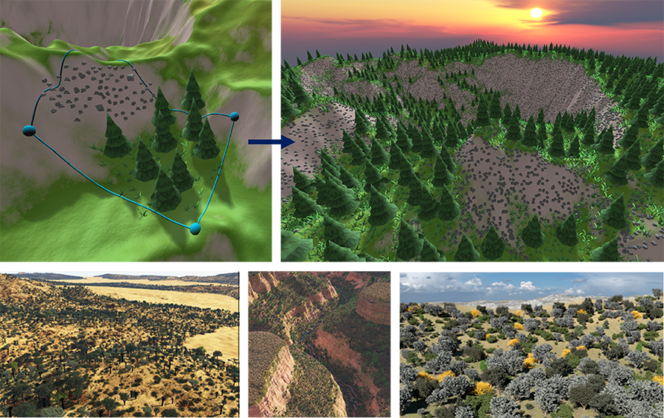

In the lab we developed this type of intelligent cut-and-paste system. Our Worldbrush tool can take a sample of a virtual landscape and replicate it, not identically, but with the same statistical characteristics. In fact, a former student from my team who worked at Weta told us that our modelling system based on sketches of hair had been used for the first Avatar film.

What other graphic elements can you help the creators of special effects with?

M.-P. C.: At Weta, they also told us that their artists could not design mountains very well. They wanted them to look genuine, with outlines that could be drawn easily, in the background behind the actors. This led to one of our research papers in which we developed a method for taking an existing landscape and deforming it from the camera’s point of view in a realistic manner. This allowed us to obtain the desired shot.

Have you ever wanted to participate more directly in the creation of a film?

M.-P. C.: I do not have the time! Those who take part in these creations spend a year of their lives doing a specific thing. I generally have five to ten projects ongoing with various students and scientific collaborators in France and abroad. We simultaneously explore different avenues. I have this freedom because I am not part of a company or start-up. When you animate a character walking in snow, a twirling dress, or a lava flow, you have to add physical knowledge to the models.

How do you go about doing that?

M.-P. C.: To create a virtual world with realistic laws, you have to base yourself on physical knowledge. In computer graphics, we have been using our experience of the real world to design models and simulations for the past thirty years. What is original about my approach is to see how this more generic expertise can be used in the phases of creation. For example, take a biologist who wants a system to produce animated sketches that function at all scales, from the entire organism down to a single cell. There are rules of repetition, and simple principles for movement and deformations, such as the conservation of volume or surface area. They enable us to move towards a generic tool of this kind.

You also develop instruments with researchers in various disciplines. How does this collaboration work?

M.-P. C.: First of all, I try to gather their top-level knowledge of a phenomenon in order to reproduce it in a virtual world. In addition, researchers serve as inspirers and testers for systems of creation, one of which can for example allow them to illustrate a situation by drawing a sketch that directly transforms into an animated 3D scene. For instance, we worked with a professor of anatomy. The idea was to use a 2D sketch of an organ to generate a 3D model that we can rotate, zoom into to add details, or on the contrary zoom out of to show where the organ in question is located in the human body.

What brought you to a field of research so closely connected to art? Did you have an artistic calling?

M.-P. C.: Ever since childhood, I have liked to draw, sculpt and produce. I created little worlds with small figures made of modelling clay, with skeletons made out of wire. I found all that again in my research, with the added advantage of watching them come to life before my eyes! But I did not have a real artistic calling, more of a creative one. And computer science has become the tool for it. I often advise young people to think of what they have always liked to do, and make it their occupation.

Tell us about your background.

M.-P. C.: Since I was a good student, and I had an older sister who was very keen on literature, my mother encouraged me to pursue scientific studies. I ended up in a preparatory class, and was fortunate enough to be accepted at the École Normale Supérieure higher education institution. I obtained the agrégation teaching diploma in mathematics, and then decided to study a discipline that was barely emerging in 1986-1987, namely computer graphics. The first thing I wanted to do was to produce natural scenes and objects within these worlds that you could create. At the time, video games had a prison-like feel: you entered a castle, a room that was generally empty, and then moved on to the next one, also empty. What’s more, we did not know how to make natural scenes to walk outside.

All of this sounds quite fun. Is that something that is important for you?

M.-P. C.: Yes, indeed. Little by little, I put elements into the algorithms that will enable me to create the virtual world I imagine. It is interesting because in shaping this universe, I am simultaneously creating the media that allows me to express myself. It is like being a painter, but in addition to a painting, I am also creating the best canvas, paint, and brushes.

That’s how it was during the Renaissance, when painters conducted experiments to improve their pigments.

M.-P. C.: Precisely! In fact, what I do is also co-creation, as in a painter’s workshop. When you work in a team, you share methods and think together, create together.

How do you see your field evolving? What are the risks and challenges?

M.-P. C.: Many people are discovering these virtual animated worlds that we have been working on for thirty years through the metaverse. However, if the latter becomes a kind of limited commercial zone in which nothing is free, and is detrimental to the planet due to 5G3 and blockchain, I don’t see the point. Why divert energy from the real world to put that in place? I fight for virtual worlds that have a meaning. For example, allowing prehistorians to travel through time and immerse themselves in the results of their theories. If our research can give sense to the metaverse, that’s fine by me. Another risk is that humanity loses some of its creative abilities.

More and more people, and researchers in particular, use deep learning to solve a host of problems. So we are losing knowledge-based models in exchange for models based on millions of examples. And this means we are no longer capable of explaining the results. In the future, I hope we will have intelligent systems that combine existing expertise with a little learning, so as to produce something that is truly effective. Something that helps humans concentrate only on the most interesting tasks. ♦

- 1. Researcher at the LIX (CNRS / École Polytechnique) and professor at École Polytechnique. She was awarded the 2012 CNRS Silver Medal, and is a member of the French Academy of Sciences.

- 2. Weta Digital (today WetaFX) helped create special effects for the films Avatar (2009), Mulan (2020), the Lord of the Rings film series, and the televised series Game of Thrones (2011-2019).

- 3. In 2020, France’s High Council on Climate deemed that the fifth-generation network standard (5G) would have a negative impact on greenhouse gas emissions, especially due to the production of new terminals (smartphones, tablets, etc.) and network equipment.