You are here

In the Days of Human Zoos

Paris, 1889. The City of Light was celebrating 100 years of “liberty, equality and fraternity.” In addition to the brand-new Eiffel Tower, the other main attraction that awaited the 28 million visitors to the Universal Exposition that year was a “Negro Village” with 400 African inhabitants, exhibited among the colonial pavilions on the Esplanade des Invalides. For the past decade, such native villages had been a feature of most international fairs, and the practice would continue well into the 20th century.

Hamburg, London, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Barcelona, Osaka… The major cities that prided themselves on their modernity exhibited people whom they considered savages in human zoos. Senegalese, Nubians, Dahomeans, Egyptians, Laplanders, Amerindians, Koreans and other so-called “exotic” peoples were put on display in environments evoking their native lands, often in tacky costumes and in proximity to wild animals. An exhibition in Brussels in 1897 even included a sign reading, “Do not feed the Congolese. They have been fed.” More than a billion people flocked to see this type of exhibition between 1870 and 1940.

How could such a thing happen? “These exhibitions did not suddenly appear in the late 19th century—they were in fact following a long tradition,” explains Gilles Boëtsch, director of the UMIESS1 laboratory and scientific coordinator of the catalogue of an exhibition held in 2011 in Paris entitled “Human Zoos: The Invention of the Savage.”2

Mass entertainment

One sadly famous example is the “Hottentot Venus,” a woman from southern Africa who was exhibited like a freak show in the UK and France in the 1810s. “What is interesting is the scale that the phenomenon had reached by the end of the century,” Boëtsch emphasizes. “It became a form of mass entertainment.” It is also worth noting that the vast majority of the people put on display were paid and worked under contract.

Why were these shows so successful? “First of all, there was a massive migration from rural to urban areas, filling the cities with people avid for entertainment and edification,” Boëtsch notes. "They were fascinated by this type of exoticism, which they had never seen before.” During this transitional era, the human displays also evoked the myth of a lost paradise, where man lived in harmony with the animals. The exhibitions were presented as the remains of a world that would never be seen again. In addition, the bare-breasted women also offered a sort of low-priced, respectable peep show in a puritanical society that otherwise did not tolerate nudity.

Links with colonization

“For many French people, the shows’ appeal was also linked to the loss of their village roots, allowing them—rich and poor alike—to find a new sense of belonging, with the ‘savages’ serving as a foil,” comments Éric Deroo, a visiting researcher at the Laboratoire Anthropologie Bioculturelle.3 “In Europe at the time, national identities, which had previously been rather vague, were being forged. In the name of modernity, all differences had to be wiped out in favor of citizenship,” he says. “The French exhibitions also featured villages representing the Brittany and Savoy regions, which were deemed backward and in need of modernization, just like Africa or any other colony in those days!” adds Boëtsch.

Indeed, the colonies played a central role in the emergence of human zoos, according to the historian Pascal Blanchard, a visiting researcher at the LCP4 and co-director of the ACHAC Research Group. “It was no coincidence that governments decided to include these exhibitions in their major fairs, paid to bring in thousands of men and women and gave them all the necessary authorizations,” insists the researcher, who served as scientific curator5 of the 2011 exhibition. “It was part of a policy that sought to legitimize colonization, which was a booming in the 1860s to 80s.”

In essence, promoting the idea that there are “savages” was a means of winning public support in the race for a colonial empire, whether based on the pseudo-altruistic aim of bringing progress and civilization to the disadvantaged, or simply on barefaced exploitation. True enough, the various groups exhibited in each country coincided with its colonial expansion. When France defeated the king of Dahomey in 1893, members of his regiment of “Amazon” women warriors were displayed in Paris. Similarly, Japan organized an exhibit of Koreans (alleged to be cannibals!) in 1903—before colonizing the country in 1910.

Scientific racism

Science came to play a complex role in this situation. At first, anthropologists were eager to see the exhibitions, especially at the Jardin d’Acclimatation in Paris, which was managed by the naturalist Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire. Their main goal was to take measurements, which they were obsessed with at a time when an increasing number of theories based on the biology of races were coming to the fore. Having “specimens” close at hand seemed remarkably convenient. Sixty years earlier, the “Hottentot Venus” (see above), who represented what Boëtsch calls “a turning point in the history of human exhibitions,” had already reconciled the interests of the worlds of both entertainment and science. Convinced that he had found proof of the congenital inferiority of “races with a depressed and compressed cranium,” the anatomist Georges Cuvier actually dissected the young woman’s body after her death in 1815, and presented jars containing her organs to the Academy of Sciences.

“However, as of the 1880s many scientists raised doubts about the representative nature of the people displayed in enclosures, as well as the whole concept of a pure race,” notes Claude Blanckaert, a researcher at the Centre Alexandre-Koyré.6 “Fewer scholarly delegations came to the exhibitions. The presumed alliance between science and public opinion was disavowed, sparking heated debates in the academic world.”

Even more complex is to determine how much influence these human zoos had on the popularization of racism and its accompanying prejudices. According to Boëtsch and Blanchard, there is a direct link: “The anthropo-zoological exhibitions were the main vector in the transition from scientific racism to widespread colonial racism. For the visitors, the mere sight of these populations behind bars—real or symbolic—was enough to clarify the hierarchy: it was obvious where the power and knowledge supposedly lay.” According to the two researchers, racial theories were still largely unknown to the general public at the time, because few people ever read anthropological papers and the dissemination of scientific knowledge was virtually nonexistent, even though popular literature promulgated the clichés.

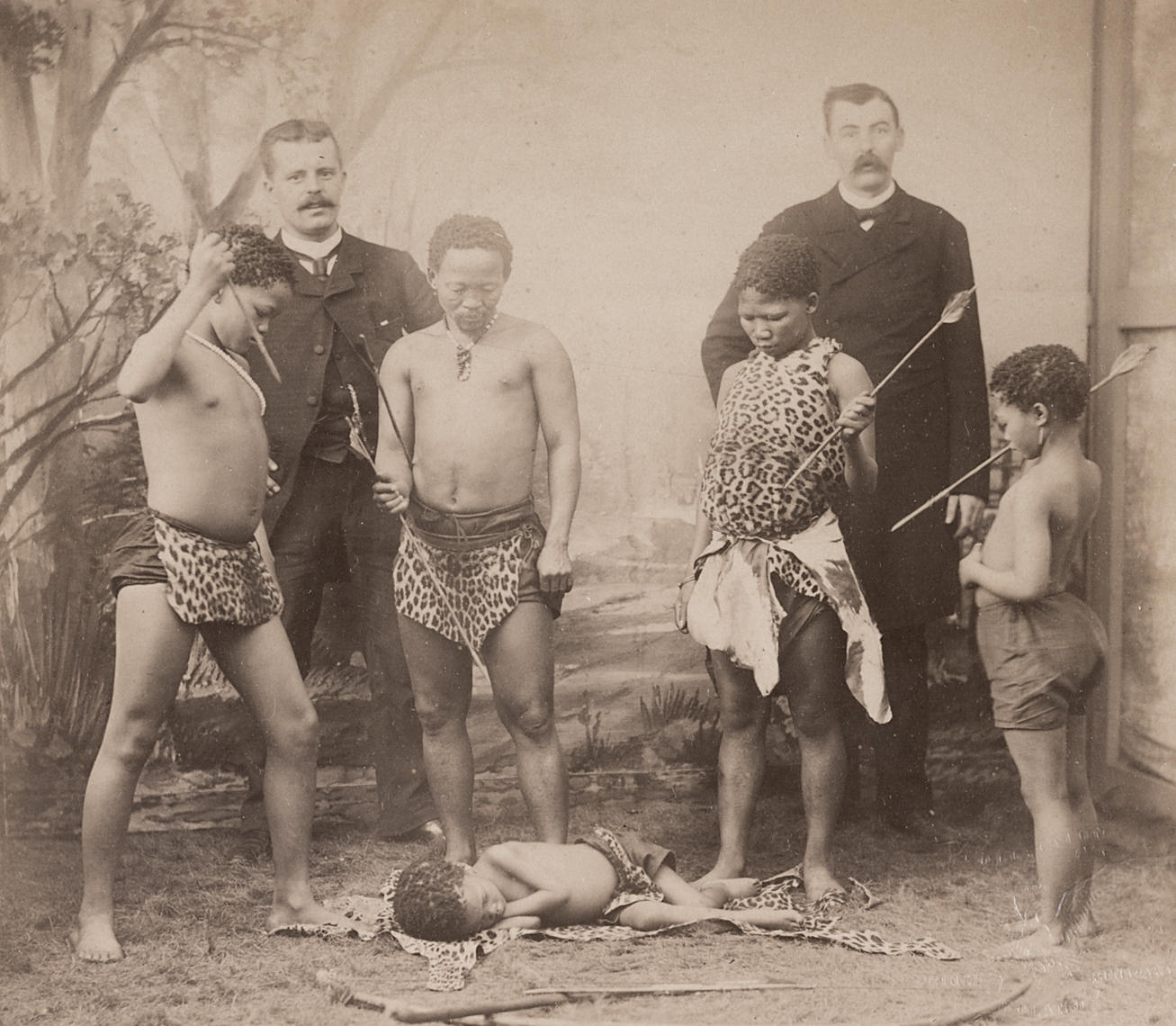

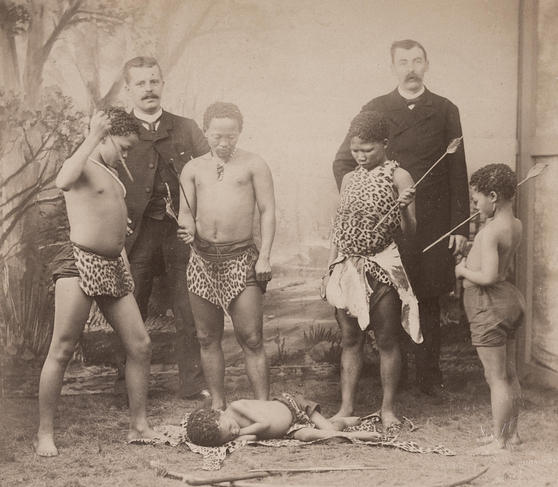

It therefore seems that the exhibitions—as mass entertainment—contributed to the rise of widely held racist views—backed up by photography, a medium that was then growing in leaps and bounds. Many purportedly educational postcards were produced to accompany the exhibitions, often with made-up ethnographic information printed on the back.

The influence of literature

According to Blanckaert, however, “this hypothesis supposes that scientific racism predates common racism. Yet the process could easily be reversed and scientific racism be interpreted as a mere rationalization of common beliefs.” The lack of protest against human zoos seems to support this point of view, presumably indicating that racism was already largely interiorized, whether consciously or not.

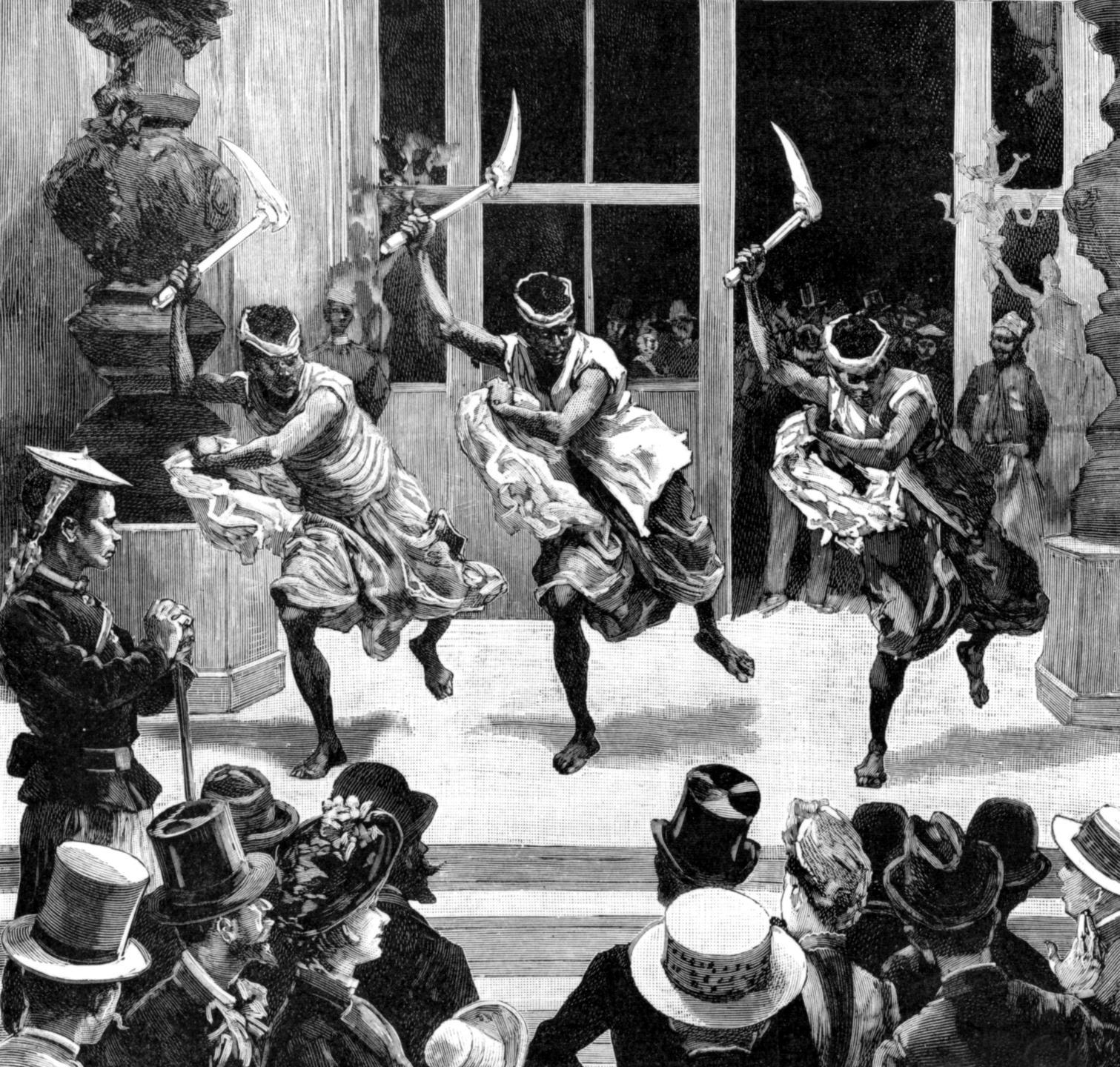

“Towards the end of the 19th century, schoolchildren were already being issued natural history textbooks that started with a chapter on the world’s races, placing Europeans at the top of the hierarchy,” Boëtsch agrees. Blanckaert also underlines the influence of literature: “The writer Léon-François Hoffmann demonstrated quite some time ago that the popular literature of the 18th and 19th centuries clearly anticipated the evolutionist comparatism that underpinned the ethnic exhibitions by placing the negro slave on a developmental par with monkeys or children.” Lastly, there is simply little evidence of what people thought in those days. “There are no archives on the audiences at the fairs, or clues about their mindsets, or what shocked them,” Blanckaert points out. Some exhibitions showed Laplanders eating raw meat on cue, or Africans shaking their spears at set times eight times a day. In the evening, ferocious Zulus danced on stage at the Folies Bergère cabaret! The question is whether the audience knew they were only watching actors in a show, insulting though it may have been?

Multiple factors at play

“It would be presumptuous to propose simplistic explanations for complex occurrences,” Blanckaert warns, while praising a documentation and research work that reveals, for the first time, the real extent of the practice. “More than 70 authors contributed to the exhibition catalogue, highlighting the complexity of a phenomenon that spanned nearly five centuries, with many local specificities and chronological interruptions,” Boëtsch and Blanchard add. “It is important to bear in mind that there is no single model for human zoos, but rather a plethora of intertwining and sometimes opposing factors, which ultimately gave rise to a global phenomenon starting in the 19th century.”

By casting light on this shameful chapter in history, the Paris exhibition, one of the first of its kind in the world, served a clear goal: “to deconstruct representations, seen at the time by more than one billion spectators and inevitably influencing the way we see the world,” Blanchard concludes. As recently as 1994, the French biscuit manufacturer Saint-Michel joined forces with a Safari park near Nantes to create an “Ivory Coast village.” Its name caused a scandal and was soon changed: the attraction was originally named “Bamboula’s Village” after a now-discontinued Saint-Michel brand of chocolate biscuits featuring a caricature of an African boy named Bamboula.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

A long tradition of exhibitions

• Ancient Egypt: an exhibition of dwarfs from Sudan.

• Late 15th century: native Americans, living specimens brought back from the New World, were paraded as curiosities in the royal courts of Europe.

• 1654: Inuit were exhibited to the king of Sweden.

• 1774: James Cook returned to England with Omai, a Tahitian dubbed the “Noble Savage,” who became the subject of a play.

• 1810: Saartjie Baartman, the “Hottentot Venus,” was exhibited in a cage in London. She then became an attraction in Paris, where she died in 1815.

• The 1820s: London saw a string of displays of Amerindians, Lapps and Inuit, alongside freak shows featuring “Lilliputians,” bearded ladies and limbless men. Encounters with the “Other,” the stranger from a strange land, became a genuine form of entertainment for modern societies.

• 1853: A troupe of Zulus embarked on a grand tour of Europe.

• 1874: In Hamburg, Carl Hagenbeck, seeking to emulate the circuses and “ethnic shows” promoted by P. T. Barnum in the US, became the first to combine the two genres by exhibiting a family of six Lapps accompanied by two dozen reindeer.

• 1877: Hagenbeck came to Paris to exhibit a troupe of Nubians at the city zoo, which was suffering from a shortage of attractions since its animals had been eaten during the siege of 1870.

This article was originally published in French in CNRS le Journal #263 (2011).

- 1. Environnement, Santé, Sociétés (CNRS / Université Cheikh Anta Diop (Dakar, Senegal) / Université Gaston Berger (Saint Louis, Senegal) / Université des Sciences, des Techniques et des Technologies in Bamako (Mali) / Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique et Technologique (Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso).

- 2. November 29, 2011 to June 3, 2012 at the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris.

- 3. CNRS / Université de la Méditerranée / EFS.

- 4. Laboratoire Communication et Politique (CNRS / Université Paris Dauphine / PSL Research University Paris).

- 5. With Nanette Jacomijn Snoep, anthropologist in charge of the history collections of the Musée du Quai Branly.

- 6. CNRS / EHESS / MNHN.

Explore more

Author

Science journalist, author of chilren's literature, and collections director for over 15 years, Charline Zeitoun is currently Sections editor at CNRS Lejournal/News. Her subjects of choice revolve around societal issues, especially when they interesect with other scientific disciplines. She was an editor at Science & Vie Junior and Ciel & Espace, then...