You are here

Hunting for the Origins of Humankind

From April 25 to May 5 2016, geomorphologist Laurent Bruxelles and his colleagues Marc Jarry and Grégory Dandurand set off on a two-week expedition in Namibia. Their aim was to discover and explore caves, which, the scientists believe, may harbor human remains that could shed fresh light on the origins of humankind in Africa.

Monday 25 April: Arrival in South Africa

On a ridge overlooking the Kromdraai excavation site in South Africa, three men watch the sun go down behind the hills of the Bloubank River Valley. Geomorphologists Laurent Bruxelles1 and Grégory Dandurand, together with archeologist Marc Jarry, from the INRAP2 and the TRACES laboratory,3 are conducting the first exploratory mission in the 'Human Origins in Namibia' program.4 An expedition that is to take them to one of the wildest regions of Namibia, the Aha Hills range.

Before setting off for these remote hills, Bruxelles and his companions have come to "get a feel" for the cradle of humanity, near Johannesburg. Bruxelles, a specialist in karst, knows the site well. In 2007, he joined the team led by the South African paleoanthropologist Ronald J. Clarke, who discovered the famous fossil Little Foot. Last year, their collaboration enabled them to push back the age of Australopithecus. It has now been dated back to 3.7 million years ago, 500,000 years before Lucy, the Australopithecus afarensis co-discovered by Yves Coppens in Ethiopia in 1974.

With this find, South Africa was back in the race to elucidate human origins, a quest that Bruxelles intends to join as he sets out to uncover fossils in Namibia.

"The whole of Africa is definitely the cradle of humanity," he says. "What you have to look for are fossil traps, such as the Great Rift Valley in East Africa and caves in southern Africa. This is why we're going to a completely unexplored region of Namibia to look for caves, examine breccia, search for fossils and see if we can find new pieces of the cradle of humanity."

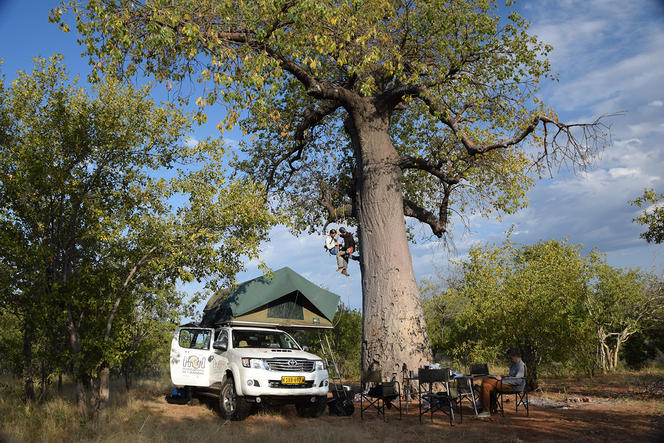

Thursday 28 April: Baobab camp

After taking off from Jo'burg, as South Africa's economic capital is dubbed, the plane taking the team to Namibia is caught up in a violent storm right over Windhoek, the country's capital city. The aircraft makes a rough touchdown on the wet runway but immediately takes off again, engines roaring. On board the plane, passengers start to panic, tightening their seatbelts and calling out to the flight attendants, while some even take out a Bible and start praying. After circling twice, the aircraft finally lands at Windhoek's small airport.

After a night's rest, Bruxelles, Jarry and Dandurand pick up a rented four-wheel drive and pack it with 400 kilos of material, food and water—enough for ten days of complete self-sufficiency out in the remote regions they are about to explore. Their 800-kilometer journey will take them across the country from west to east, including 300 km along straight, dusty trails. After a day and a half's drive, they are finally approaching their first campsite, now only thirty kilometers away. It's pitch dark. The trail peters out in the tall grass. Some hyenas cackle in the distance. The feeling of remoteness is so great that it is hard to believe there's a tiny village just one kilometer away.

In the morning, two men, accompanied by children and a dog, turn up at the baobab camp to collect payment for the night's stay. Better known by the colonial term, "Bushmen," the San people are the descendants of southern Africa's first inhabitants. Coffee and cigarettes are shared as conversation gets under way.

The three scientists then set off to inspect the nearby hill. Bruxelles and Jarry have already visited the site. During their brief survey a year earlier, they discovered feline footprints in a small cavity. Although their second expedition reveals neither cave nor fossils, Jarry, a prehistorian and specialist in Paleolithic population dynamics, is delighted. "There are several stone tool sites containing tools or flakes. They probably date from the Middle Stone Age, between 400,000 and 50,000 years ago. What we have here is a sort of tool factory, since the humans of that time could find the raw material they needed, in this case quartzite."

These remains are not in themselves unusual, but Namibia is a very poorly documented country. "We're in a blank area, a map we're going to fill with dots," smiles Jarry. "That's why our project focusees on human origins in the plural, both ancient and more recent."

Sunday 1 May: Okavango

After three nights in the bush and two days of exploration advancing through acacias, scrub and spider's webs, the team decides to hit the road and head for a new destination, the Drotsky's and Waxhu caves in Botswana, where they hope to get some more observational practice.

In this region, there is only one border crossing, forcing them to make a long detour to the north. The three scientists make the most of it to extend their journey and visit the Okavango, one of the largest inland deltas in the world.

"This delta is the regional base level that acts as a foundation for the geomorphological evolution of the region, including the formation of caves," Bruxelles explains. A well-earned break in a lodge, with a hot shower, a good meal and a comfortable bed help the team recharge their batteries in one of Africa's most dramatic landscapes.

Monday 2 May: Drotsky's Caves

Around fifty kilometers south of the Aha Hills range, a long hill made of black rock rises above the acacia-covered dunes of the Kalahari desert. At its base, two caves called Gcwihaba ("Hyena's Hole") by the Sans are more commonly known as Drotsky's Caves, after the the first European— a local farmer—to have been shown them in 1934. A wealth of stalactites, stalagmites and draperies abound in this dried up labyrinthine network, but there's something even more impressive. As one goes deeper into the cave, the ground becomes covered with an ever-thicker layer of greyish powder. This blanket of excrement and crumbled rock is the centuries-old work of a colony of bats that cover the walls of the galleries.

Here, where it is easy to lose track of time and space, Bruxelles, Jarry and Dandurand are studying concretions and rocks, hoping to find breccia, a natural concrete that can contain bones and stone tools or weapons. Near the exit, behind a stalactite, the red color of a bed of sand and clay gravel cemented by calcite indicates its external origin. On the other side of this breccia plug, back out in the open air, the three researchers search the scrub above the entrance looking for breccia laid bare by erosion.

And then they spot it: outcropping from the curved surface of a rock, a fossilized bone appears. This find lends weight to their hypothesis that bone-bearing breccia can be found in the caves of the Aha Hills.

Tuesday 3 May: Dancing Spot

The following day, the scientists continue their observations in the area's known caves. The two Waxhu sinkholes plunge down to a depth of 70 and 50 meters, respectively. South African speleologists explored them in 2010, without realizing their paleontological significance. To get to the deeper of the two sinkholes, the team has to make its way through two kilometers of extremely dense forest. Leading the way with a 100 meter-long rope over his shoulders, Bruxelles keeps an eye on the ground, looking out for snakes and roots. Behind him, Jarry and Dandurand carry the supplies and material needed to explore the caves.

Jarry suddenly freezes. The entrance to the sinkhole is only fifty meters away, but two big cats have just bolted into the bush. Their general appearance, their coats and the sudden musky smell carried by the wind leave little doubt: two female lions are somewhere close by. After a rapid discussion the group quickly turns back, making a wide detour to avoid any danger. "The lionesses have left, but there may be a lion and and its cubs. If we go down the sinkhole and they come back in the meanwhile, we won't be able to get back to our vehicle at sundown this evening. Science has to stop when there are lions around," Bruxelles concludes.

Disappointed, the three scientists fall back on Waxhu South, the smaller of the two sinkholes, which overlooks the Dancing Spot, a meeting place for the Sans. After two hours of hard work hammering in pitons all the way down the wall, the team abseils down the 52 meters of this vast chamber hollowed out of a hill made of marble. With a length of 40 meters and width of 10 meters, the cavity is so huge that the light from their lamps can hardly penetrate the darkness. At the bottom of the sinkhole, the researchers discover a freshly killed rattlesnake lying on the scree. Venom drips from its fangs, a sign that it may have fallen there when the scientists arrived. Just next to it, an intact bird skeleton attracts Bruxelles' attention. Almost completely buried, the bird has begun the long, delicate process that will, perhaps, convert it into a fossil thousands of years from now.

One final surprise awaits the group as they climb back up. Curled up under a rock, a python is using its forked tongue to sense the odor of the climbers as they pass by. Bruxelles, whose young son owns a specimen, takes a closer look at the snake. "It's not dangerous," he says. "It must have fallen there, and will probably starve for want of prey."

Even though it has no fossil-bearing breccia, the cave is the typical kind of cavity the three scientists are looking for. "We don't know how much material has accumulated at the bottom of the sinkhole, but it could be several tens of meters in depth," Bruxelles points out. "Traps of this type have probably always existed, and, depending on their history, could contain the remains of hominins such as Australopithecus."

Wednesday 4 May: Marula camp

The final stage of the expedition takes place a few kilometers away, on the Namibian side of the border. It takes another day's drive to reach the most remote campsite of the journey, at the end of a thirty-kilometer sandy trail .There is no cellphone coverage. No village nearby. Camping at the foot of a tall marula tree, whose fruit regularly thump onto the ground, the group's feeling of isolation is complete.

Until the following Saturday, the team explores three more densely vegetated hills—a painstaking, unrewarding task, as all they find is a small cavity inhabited by porcupines. Not that this discourages the scientists, who are used to the ups and downs of research. "You can look for caves in vain for four days, and end up discovering a whole series of them on day five," Bruxelles points out. "The paleontologist Michel Brunet explored Chad for fifteen years before he found the Toumai fossil in the Djurab desert. We have forty more hills left to explore systematically. There's no reason why we shouldn't find caves in this part of the range. For every specialist, Namibia is the place to look. The Aha Hills may well harbor one of these highly coveted fossils."

- 1. Laurent Bruxelles is joint director of the Pôle Afrique at the TRACES laboratory.

- 2. Institut National de Recherches Archéologiques Préventives.

- 3. Travaux et Recherches Archéologiques sur les Cultures, les Espaces et les Sociétés (CNRS / Université Toulouse Jean-Jaurès / MCC / EHESS / Inrap).

- 4. Mission funded by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Development.

Explore more

Author

A graduate of the Toulouse School of Journalism, Gael Cerez is a print media and Web journalist.