You are here

How the Dreyfus Affair Went Global

A crucial episode in the history of the Third Republic and a prime example of miscarriage of justice, the arrest and conviction of Captain Dreyfus had a tremendous impact in France and around the world. Could you briefly summarise the essential elements of the Dreyfus Affair?

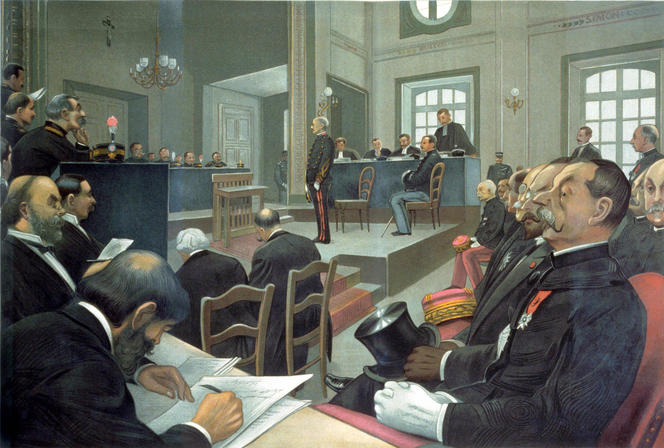

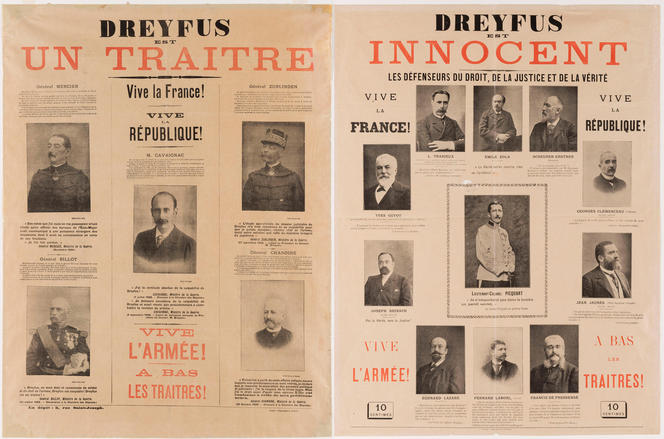

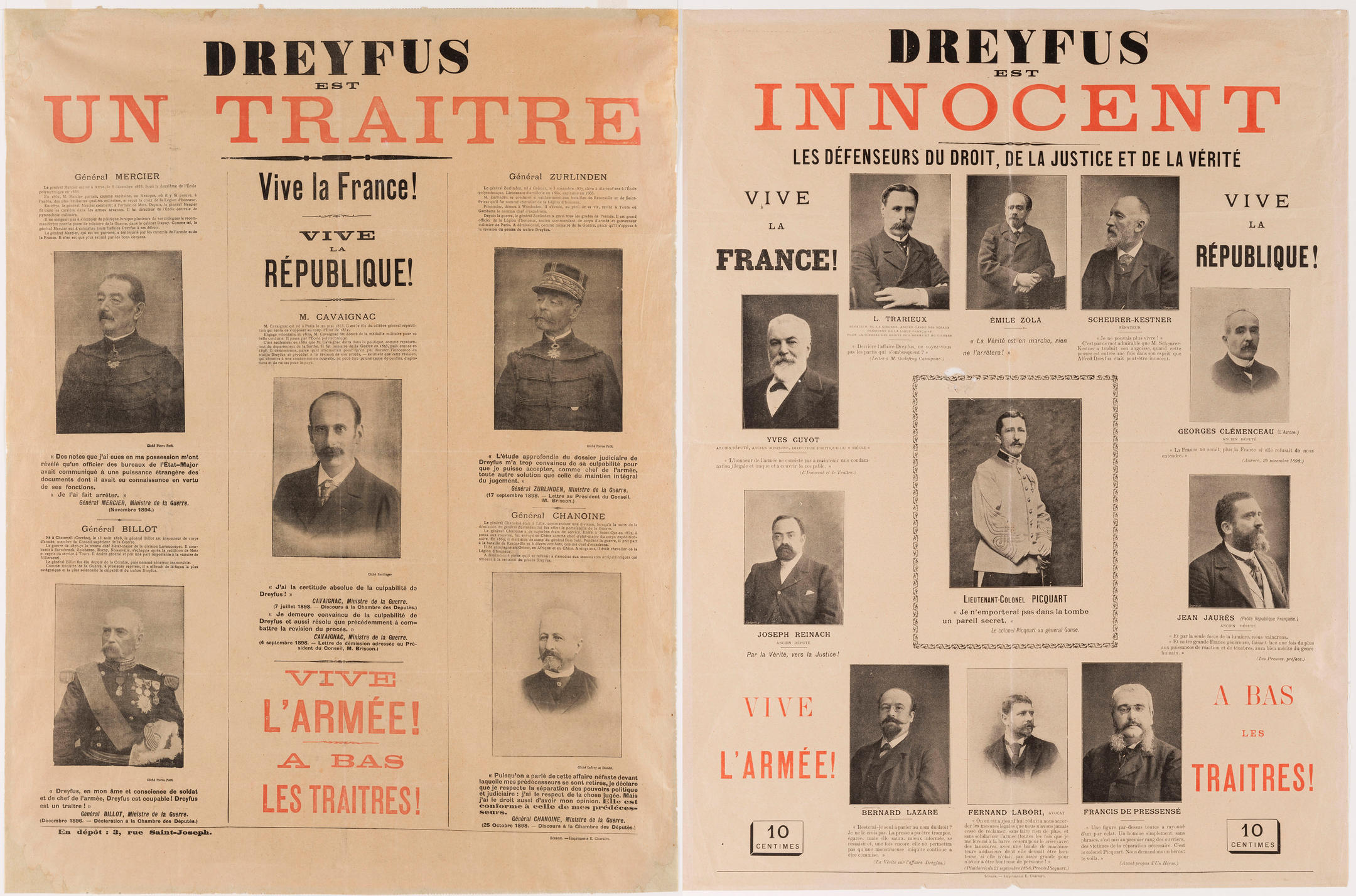

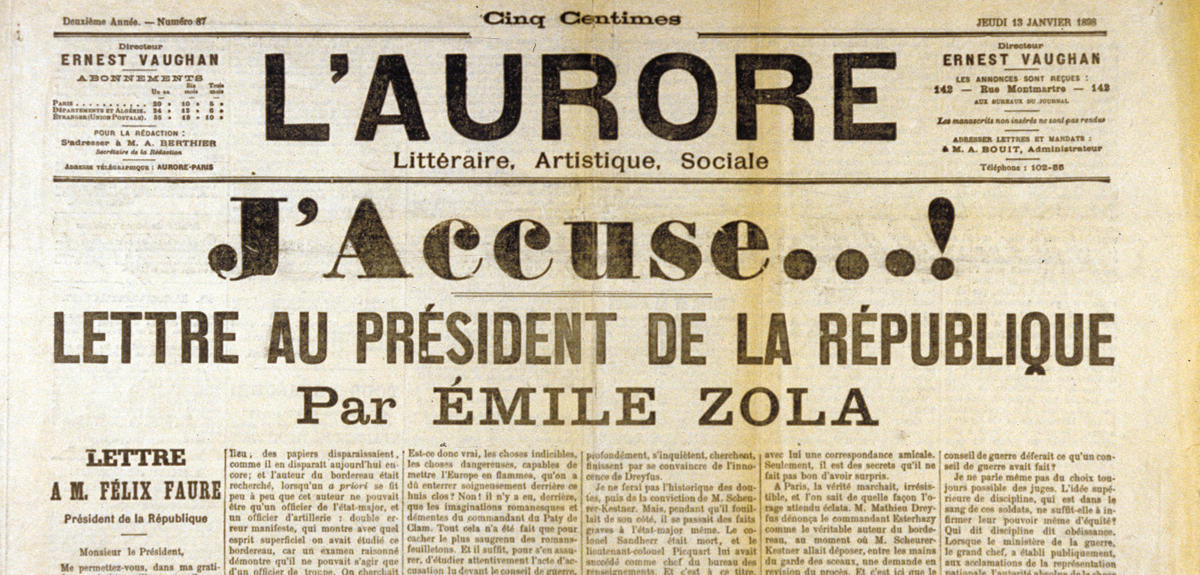

Olivier Lumbroso:1 On 15 October, 1894, Alfred Dreyfus, an army captain of Alsatian Jewish descent, was accused of divulging military secrets to Germany. He was arrested, convicted and sentenced to deportation. Stripped of his rank on January 5, 1895 he was sent to the penal colony on Devil’s Island in French Guiana. Over the months, a political and media campaign waged by the pro-Dreyfus camp finally led to the identification of the real traitor, Major Esterhazy. On 13 January, 1898, Zola, who was by then one of the world’s most translated writers, published the pamphlet “J’Accuse” in the newspaper L’Aurore, with a circulation of 300,000 copies. His essay made the Dreyfus case an international affair. Convicted of libel, Zola fled into exile in England as France was torn apart against a background of hatred. A new trial in Rennes in 1899 ended with another conviction, and the affair finally came to a close on 12 July, 1906: Dreyfus was found innocent by the Cour de Cassation (highest court of appeal) and was reinstated in the army with the rank of Major. Esterhazy, meanwhile, was never convicted.

Was the stigmatisation of the Jewish community, which was already considerable in the 1880s, exacerbated by the Dreyfus Affair?

O.L.: The hostility towards Dreyfus, towards Jews and towards Zola was accompanied by violent anti-Semitic riots in the big cities. In the late 19th century the extreme right’s anti-Semitism had a strong influence on public opinion, notably through the writings of Édouard Drumont, whose ideas expressed in La France Juive (1886) were upheld by the anti-republican newspaper La Libre Parole, which denounced “the fate and curse of the race.” These points of view were shared by many French nationalists, who saw the Jews as foreigners in their land, nomads incapable of integrating, allies of the Freemasons, the killers of Christ, etc… Not to mention Action Française, a political movement launched in 1898: virulently anti-Dreyfus, it was upheld by the monarchist Charles Maurras and backed by the politician and writer Maurice Barrès.

Did the anti-Semitism unleashed by the Dreyfus Affair prompt some Jews to leave France?

O.L.: Well before the founding of the State of Israel in 1948, a few thousand European Jews left to settle in the first agricultural colonies in Palestine. In 1896 the Austrian journalist Théodore Herzl, shocked by the violence surrounding the Dreyfus Affair, which he was covering as a reporter, proposed the creation of a Jewish state. He organised the First Zionist Congress in Basel (Switzerland) the following year.

Zola was not an early defender of Dreyfus when the latter was convicted for the first time in December 1894. Why?

O.L.: Zola’s pro-Dreyfus stance was not a spur-of-the-moment, reckless, impulsive activism, nor was it a publicity stunt to boost his career, as some of his detractors insinuated. What he did was well thought out. In May 1896 he published an article in Le Figaro daily newspaper denouncing anti-Semitism without getting involved in the affair, which he merely observed from afar. He gradually became convinced of Dreyfus’s innocence, in particular through his contacts with the journalist Bernard Lazare and the vice president of the Senate, Auguste Scheurer-Kestner. In fact, joining the battle for the rehabilitation of Captain Dreyfus was not without risks. Zola was convicted of libel following his open letter to President Félix Faure and was forced to leave France for London on 18 July, 1898 – an exile that would last until June 5, 1899. Ultimately, the fictional material brewed up by this socially conscious author, who firmly believed that justice could triumph over obscurantism, reason of state, the established order, etc., bore a striking resemblance to real life and, often, to the Dreyfus Affair itself. Certain characters in La Bête Humaine confront the issue of miscarriage of justice and Le Ventre de Paris touches on the theme of deportation. In a sense, the art of fiction prepared Zola, perhaps subconsciously, to stand up for Dreyfus. His naturalism was his ethical and political training ground.

Did the shockwave of “J’Accuse” spread beyond France?

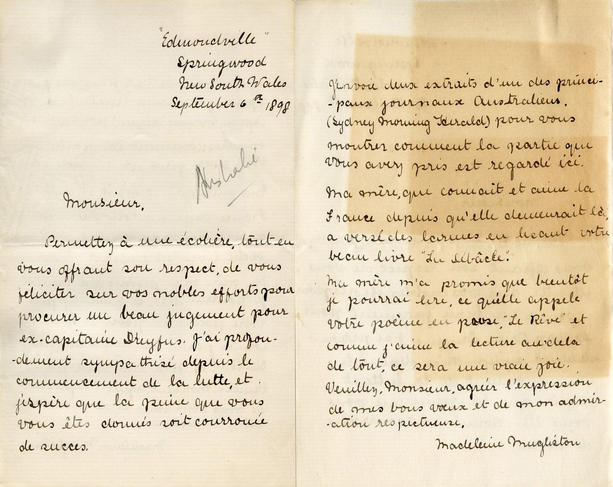

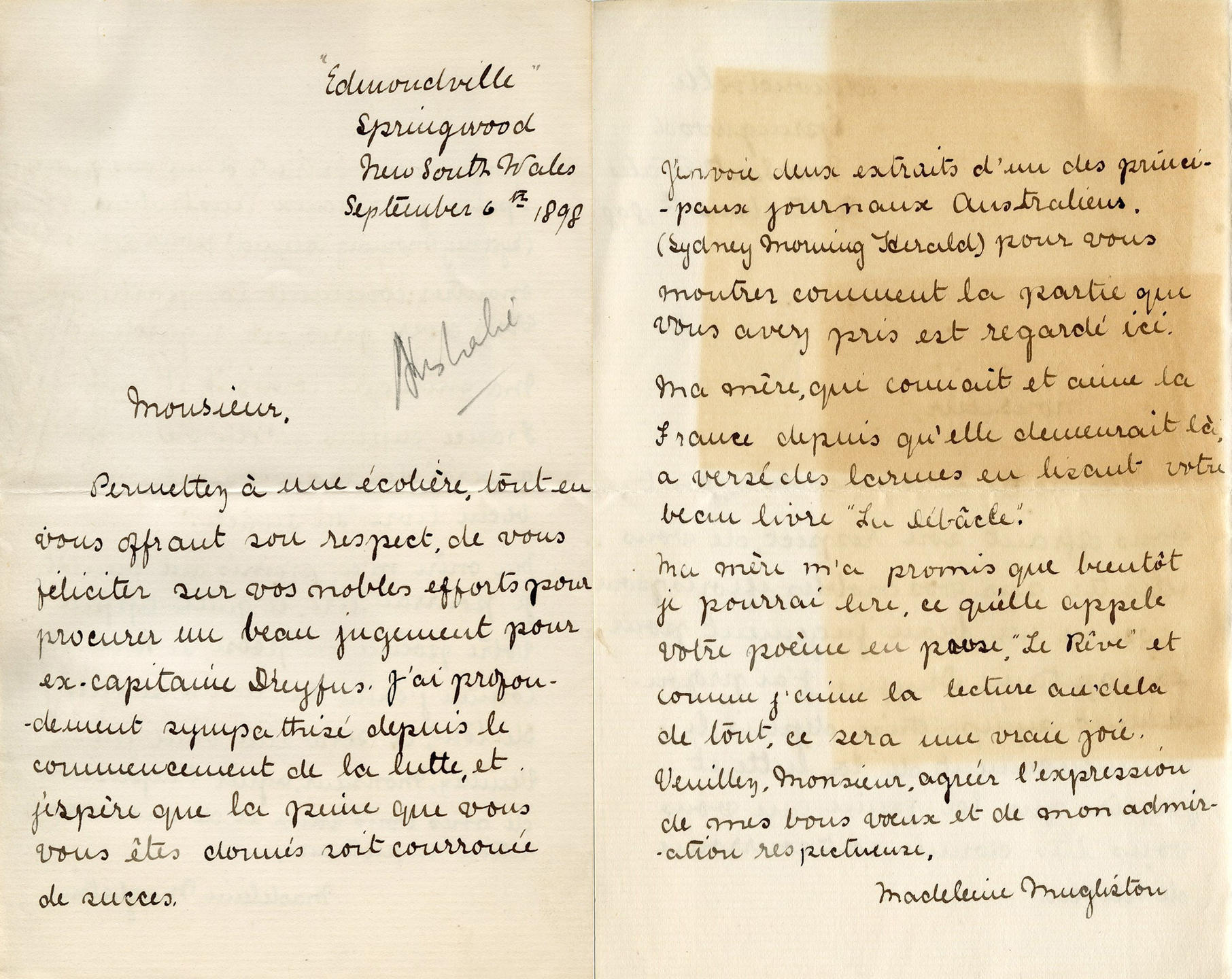

O.L.: It did. Newspapers the world over translated and published the text, sometimes literally, sometimes with commentary, depending on their editorial stance. Yet the foreign press was not exclusively dominated by Dreyfusism. The international media landscape also included an anti-Dreyfus camp, most often linked to radicalised Catholicism. Dreyfus’s second conviction in 1899, with mitigating circumstances, also made worldwide news. But above all, the publication of “J’Accuse” triggered a flood of letters addressed to Zola from across the globe.

In all, how many letters did Zola receive from outside of France between 1898 and his death in 1902?

O.L.: Several thousand. So far 1,750 have been digitised by the Zola team at the ITEM,2 most of them written individually or collectively by anonymous correspondents of both sexes, all ages and all social ranks (doctors, lawyers, workers, farmers, militant socialists…). Some came with enclosures: drawings, long poems in praise of Zola… And 1,200 of them have been made available online via the ITEM’s E-Man platform. However, we are far from having examined the entire body of correspondence, much of which is still stored in the archives of Dr. Brigitte Émile-Zola, the novelist’s great-granddaughter, and thus remains unreleased.

Who were these letters primarily addressed to, the writer of realist novels or the activist intellectual defending truth and justice?

O.L.: Most of the letter writers associated both facets. And many paid tribute, some in quite lyrical terms, to a mythologised Zola, seen as a religious figure (he was compared to Moses and Christ, even though he was an atheist) or as a heroic secular figure like Napoleon.

Most of the letters were written in French. Why was that?

O.L.: For many of their writers, simply because French, even if they didn’t know it well, was the language used by Zola to write his novels and “J’Accuse”. In other words, a language rich in moral and civic values that inspired the strength and courage to cast aside one’s own mother tongue and usual ways of thinking. To write to the Master in French, especially for those who lived under authoritarian regimes, was to use the language of freedom and enlightenment, of Voltaire and his Dictionnaire Philosophique, of the French Revolution… In fact, each letter is written in its own distinctive French — some with strikingly inventive neologisms, like the one from Elsa of Budapest (Hungary), dated 13 January 1898, which refers to Zola’s “intimidité géniale” (“brilliant untimidity”). It would be interesting for ethnolinguists to study the variations in the French used depending on the geographic origin of the letters. More broadly, this body of correspondence is invaluable as a sociological and ethnographic testimony, in that it is rooted in the ideological, political and cultural backgrounds of ‘ordinary’ Zola readers from around the globe. And it makes it possible to chart the spread of the naturalist movement outside of France.

Could we see in all of these voices from many countries a collective global outcry heralding today’s social networks?

O.L.: The idea is anachronistic, but tempting. What we can say is that this planetary outcry was made up of individual consciences, each identifying personally with the suffering of a man, in this case a Jewish man, and finding the courage to pen a letter to a writer of Italian origin. Each letter writer, whether Jewish or not, seemed to be saying, “I mean nearly nothing in this world, and yet I must raise my voice for Dreyfus and Zola.” The letters, whose educational merits could be put to good use in our schools at a time of rising nationalism, made the author of Les Rougon-Macquart realise the transformative power of his novels and activism on a part of world opinion at the close of the 19th century.

More on the conference held May 23-24 in Paris

- 1. Olivier Lumbroso is a professor of French language and literature at the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle - Paris 3 and co-director of the Centre Zola at the Institut des Textes et Manuscrits Modernes (ITEM – CNRS / ENS). He organized this conference with his colleagues Jean-Sébastien Macke and Jean-Michel Pottier.

- 2. CNRS/ENS Paris.

Explore more

Author

Philippe Testard-Vaillant is a journalist. He lives and works in south-eastern France. He has also authored and co-authored several books, including Le Guide du Paris savant (Paris: Belin) and Mon corps, la première merveille du monde (Paris: JC Lattès).