You are here

Being gay or lesbian under Nazi rule

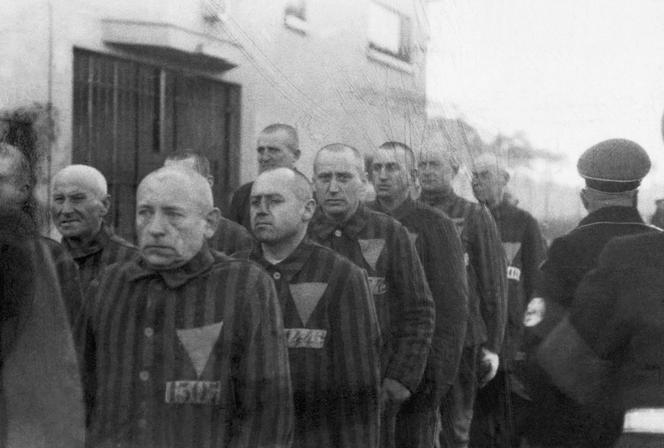

It is now an accepted fact: between 1933 and 1945, the brutality of the Nazis, who sought to “purify” the “Aryan race,” took a heavy toll on homosexual men, seen as carrying a “contagious vice.” Accused of violating Paragraph 175 of the German Criminal Code—according to which “a man who commits a sexual act with another man is to be punished by imprisonment”1— 50,000 to 100,000 men, mostly Germans, were incarcerated under the Third Reich, and several thousand more were interned in psychiatric institutions. By the end of the war, between 5,000 and 10,000 men suspected of engaging in homosexual practices had been deported to concentration camps, where two-thirds of them died. “Forced to wear a pink triangle, these detainees were particularly ill-treated. They were assigned to the harshest work details, like the ‘quarry’ at Buchenwald or the ‘brickyard’ at Sachsenhausen. In some camps they were also used as guinea pigs for ‘doctors’ who tried to ‘cure’ or 'neuter' them by emasculation,” recounts the sociologist Régis Schlagdenhauffen, a researcher at SIRICE2 and a member of the EHNE laboratory of excellence.3

A period of harsh repression

While this chapter of history has now been well documented by researchers in Germany, what about the lives of gays and lesbians in the other European countries during that period? To shed light on the subject, a symposium organized by Schlagdenhauffen on March 27 at the CNRS brought together historians and sociologists.4 “First of all, we must bear in mind that Germany was not the only country where male homosexuality was severely punished at the time,” emphasizes Fabrice Virgili, a SIRICE historian and member of the EHNE. “Repression, which took various forms, was also organized in the countries and regions annexed by Germany—Austria, Bohemia and Moravia, and Alsace-Lorraine—based on either pre-existing legislation or that of the Reich.” In the Lorraine region, and especially in Alsace, even though Paragraph 175 was not enacted until 1942, French homosexual men became targets of persecution.

According to Frédéric Stroh, a historian at the University of Strasbourg and Centre Marc Bloch,5 several hundred of them were expelled to the non-annexed regions of France as of 1940, while others were imprisoned, including at least 77 in the Schirmeck “reeducation camp” in Alsace, and a few in concentration camps (Struthof, Alsace). In Austria, section 129 I/b of the Penal Code, adopted in 1852 (and in force until 1971!), banned “unnatural fornication between persons of the same sex.” Here again, repression intensified after the Anschluss: in addition to the abuses perpetrated by the Gestapo and the exceptional tribunals set up by the Nazis, Viennese judges put several hundred men behind bars.

What about the repression of lesbian relationships? “Until now, research on Nazi Germany mostly focused on the deportation of homosexual men, which was essential from a memorial point of view,” Virgili points out. It is true that “only” a few dozen women were deported for lesbianism. Because in the eyes of the Nazis, their homosexuality did not prevent them from producing Aryan babies, it was never penalized by German law.6 Yet after a period of extraordinary freedom in the Berlin of the 1920s, lesbians in Germany were forced to adopt a “normal” lifestyle or remain in the shadows. Meanwhile, in the areas governed by the Austrian Penal Code, one of very few in Europe to prohibit lesbian acts (section 129 I/b), several hundred women were persecuted. “Between 1938 and 1945, 79 of them were prosecuted in Vienna for unnatural fornication,” reports Johann Kirchknopf, a historian at the University of Vienna's Institut für Wirtschafts und Sozialgeschichte. According to researcher Jan Seidl of the Prague-based Queer Memory Center, they were also targeted in Czechoslovakia, especially in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.

Going underground

While on the front the closeness to their comrades in arms could induce soldiers to forge intimate relationships, behind the battle lines, in non-occupied or “neutral” countries, gays and lesbians often kept their love lives secret. According to the Madrid-based sociologist Raquel Osborne, many Spanish lesbians developed dissimulation strategies, under a regime that expected women to “serve the family and the patriarchy.” As she explains, “these women led a double life: on the one hand, a ‘proper’ existence following the heteronormative model imposed by the Franco dictatorship, and on the other hand the life that they wanted to lead, concealed below the surface.” By marrying homosexual male friends or heterosexual protectors, or simply by pretending to be celibate, these women (and men) were able to enjoy moments of freedom while outwardly conforming to conservative social dictates exacerbated by the war.

The lifestyles of European homosexuals, both men and women, during this period of history have yet to be studied in depth. “Yet commemorating the victims of LGBT phobia remains an issue,” Schlagdenhauffen adds. “Considered ‘deviants,’ they were excluded from memorial ceremonies for many years. Today there are monuments in their honor in many cities around the world, from New York to Berlin and Tel Aviv—but not in France.” The sociologist raises a telling question: “Isn’t this counter to the ideals of our Republic?”

- 1. Enacted in 1871, it was revised on June 28, 1935 (quoted version).

- 2. Sorbonne-Identités, relations internationales et civilisations de l’Europe (CNRS / Université Paris-I Panthéon-Sorbonne / Université Paris-Sorbonne)

- 3. Writing a New History of Europe (CNRS / Investissements d'Avenir / Université Paris-I Panthéon-Sorbonne / Sorbonne Universités / Université Paris-Sorbonne / ANR / Université de Nantes / Centre de recherches en histoire internationale et atlantique).

- 4. The symposium “Being Homosexual in Europe during the Second World War” was hosted by the Labex EHNE with the backing of the Council of Europe.

- 5. CNRS / MAEE / Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung / MESR / Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

- 6. See the work of German historian Claudia Schoppmann.

Explore more

Author

"Stéphanie Arc is a scientific journalist who regularly contributes to CNRSLejournal. She also holds a degree in philosophy and is a published author and specialist of gender issues and sexuality. She has recently pulished Identités lesbiennes. En finir avec les idées reçues (Paris : éditions du Cavalier bleu, 2015). Today, her research focuses on lesbian history, culture and...