You are here

Climate: Time for Solutions?

A year ago, the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21) successfully concluded with the Paris Agreement. The historic treaty, which aims to keep the global average temperature increase to below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, came into force on Friday 4 November 2016, a positive sign for the COP22 as it opened in November in Marrakech, Morocco. However, much remains to be done and if the objective is to be met, the delegates still need to come up with concrete solutions.

In addition to the main conference, a host of symposia and events were being organized to enable the scientific community and civil society to share each other's data, tools and demands, providing the perfect opportunity to understand researchers' expectations and concerns with regard to agreements that are often marked by politics and diplomacy. The CNRS delegation to the COP22 was coordinated by Agathe Euzen, an anthropologist, deputy scientific director of the CNRS's Institute of Ecology and Environment (INEE) and researcher at the LATTS,1 who would be taking part in various events connected to the conference. Subjects discussed includde the Great Green Wall against desertification in the Sahel, and assessment of solutions with regard to water policy, in cooperation with the French Water Partnership.

"People are surprised when they find out about the COP22," Euzen admits. "They don't realize that the conference is held once a year. We need to show them how climate change is also linked to biodiversity, urban management, social inequality, and so on. These issues need to be put in a wider context and a long term perspective, and it is essential to explain how societal challenges become scientific challenges."

Action at every level

Although agreements are implemented by national governments, numerous actions take place at the local community level. Tackling climate change does not just boil down to a battle between industry and climate scientists, with governments acting as sole arbiters. Euzen insists on the complementary role of the various actors, whether legal experts, economists, sociologists, geographers or climate specialists. Thierry Dutoit, senior researcher at the Mediterranean Institute of marine and terrestrial Biodiversity and Ecology (IMBE)2 and a scientific advisor at the INEE, shares this view: "INEE researchers are involved in the COP to provide operational expertise in the fight against climate change," he explains. "We prefer ecological engineering solutions, which are smaller-scale and more sustainable, to geo-engineering, which sometimes smacks of science fiction and could have serious secondary effects on the functioning of the biosphere."

These researchers do not focus on the large-scale capture of solar energy or on storing carbon in the oceans. But their approach can consist in promoting good management of wetlands so that carbon can be sequestered in their peat, or in vegetating urban areas. When added up, all these projects, which are applicable even in developing countries, could make all the difference.

Focusing on local initiatives makes even more sense knowing that, despite the signature of the Paris Agreement, some politicians continue to deny the reality of climate change. Donald Trump, for example, vowed to withdraw from the Paris Agreement if he won the US presidential elections.

Sharing knowledge to save the climate

Dutoit is adamant: "The data and understanding provided by scientists are politically neutral. We haven't pledged allegiance to zero-growth ideologies," he says. "Our work is the result of experimental research that has been sufficiently published and scrutinized to be taken seriously. We have two goals: to ensure that our expertise is taken into account, and to respond to public policies with innovative and workable engineering solutions."

On the lookout for evidence and resources to assess the situation, researchers have partly turned to traditional knowledge. In collaboration with UNESCO, Marie Roué, senior researcher emeritus at the Eco-Anthropologie et Ethnobiologie laboratory3 organized a conference entitled "Indigenous knowledge and climate change," which was held in Marrakech on November 2nd-4th as a contribution to the COP22. Indigenous peoples are affected in two ways by climate change: they are especially vulnerable but have also accumulated the knowledge they need to adapt to it.

Roué's work focuses on the Sami people, groups of reindeer herders in Scandinavia. Global warming is threatening the reindeers' grazing land and is also encouraging the arrival of heavy industry. Rising temperatures and melting permafrost are reducing the cost of mining and energy projects in Scandinavia, increasingly undermining the herders' way of life.

"The sciences have become increasingly specialized and distinct from one another over the centuries," Roué laments. "Yet we now promote interdisciplinarity. And traditional knowledge is by nature holistic. The Sami combine the physics of snow and soils, botany and zoology in their observations, which stretch back continuously over a period of several centuries. We aim to show that this local knowledge complements modern science."

Spotlight on the Mediterranean

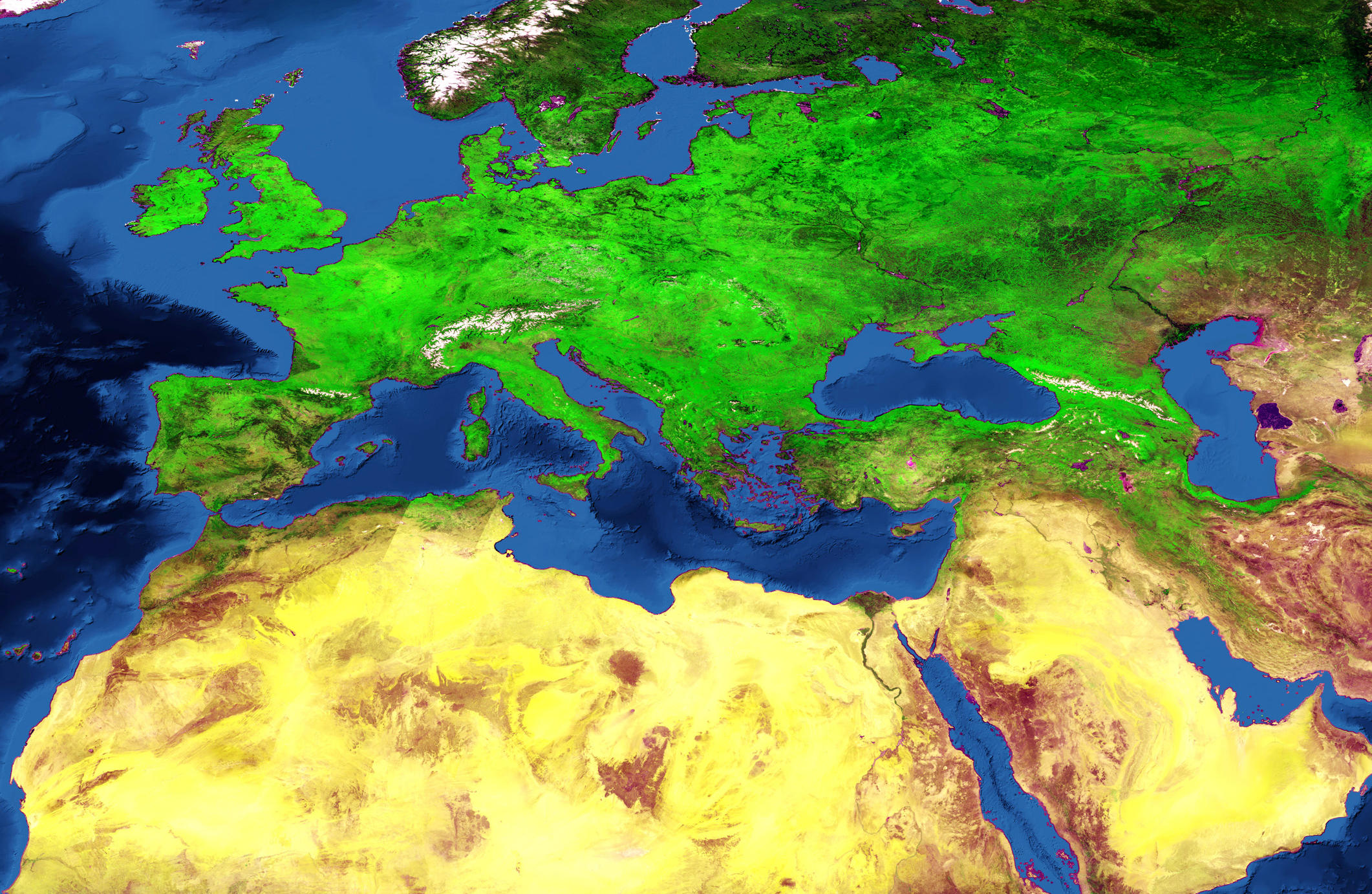

Is there a need for local solutions to global warming? In any case, the fact that the COP22 was held in an African country bordered by the Atlantic and the Mediterranean was not without significance. Joël Guiot is a paleoclimatologist and senior researcher at the CEREGE.4 Together with Wolfgang Cramer of the IMBE, he coordinates a group of experts focusing on the Mediterranean climate called MedECC.5

"The Mediterranean is a hotspot both for climate change and for biodiversity," he says. "It is located at the interface between temperate Europe and tropical Africa. The Mediterranean is a place where water, air, people and goods are exchanged, which makes it vulnerable, particularly as its coasts are densely populated." In a paper recently published in Science, the two researchers tested the various IPCC global warming scenarios in order to estimate their effect on the Mediterranean Basin. They found that only the most optimistic scenario—that of an increase of 1.5°C by 2100—can have an effect on biodiversity comparable to the variations observed over the last 10,000 years. Even the goal set by the COP21—a 2°C rise by 2100—would lead to unprecedented change during the entire Holocene. Their work highlights how much more needs to be done, despite the progress made.

"Global warming is a process with a huge inertia, and it takes several decades for its effects to be felt," Guiot warns. "If we can convince people that tackling climate change will also have short-term repercussions, for example on pollution, then we may be better able to get them to act."

The involvement of researchers in the COPs has already been extremely beneficial. Last year, Françoise Gaill, CNRS senior researcher emeritus, scientific advisor at the INEE and scientific committee coordinator of the Ocean and Climate Platform, spoke out in defence of the oceans, which finally got a mention in the preamble to the Paris Agreement. "We got them to agree to draw up a special report on the oceans and cryosphere," she rejoyces. "The situation has improved in the past year, and France has at last significantly scaled up its marine protected areas. However, it is important to continue these efforts. We need infrastructures that can benefit every country, as well as exchanges of PhD students and young researchers."

Gaill points out that projections for sea level rise between now and 2100 imply that island states will literally be wiped off the globe. Although some regions of the ocean are naturally lacking in oxygen, they are growing in size and becoming more numerous. Although the impact of climate change can be seen every day, the results of current efforts remain insufficient, showing that further commitment is needed.

"The signature last October in Kigali (Rwanda) of a binding international agreement on phasing out hydrofluorocarbonsFermerFluorinated gases used in refrigeration and air conditioning systems. In equivalent amounts, their greenhouse effet is approximately 15,000 times greater than CO2. by 2050 shows that political leaders are ready to take their responsibilities," Euzen underlines. "We have also observed that measures to protect the ozone layer have had genuinely beneficial results."

Commitment by national governments is bearing fruit, while citizens' initiatives are on the rise. Researchers stand ready to provide information to both these worlds, and help them build closer ties.

- 1. Laboratoire Techniques Territoires et Sociétés (CNRS / Ecole des Ponts Paris Tech / Université Paris-Est-Marne-la-Vallée).

- 2. CNRS / Aix-Marseille Université/ Université d’Avignon/ IRD.

- 3. CNRS/ MNHN/ Université Paris Diderot.

- 4. Centre de Recherche et d’Enseignement de Géosciences de l’Environnement (CNRS / Aix-Marseille université / IRD / Collège de France).

- 5. Mediterranean Experts on Climate and environmental Change.

Explore more

Author

A graduate from the School of Journalism in Lille, Martin Koppe has worked for a number of publications including Dossiers d’archéologie, Science et Vie Junior and La Recherche, as well the website Maxisciences.com. He also holds degrees in art history, archaeometry, and epistemology.