You are here

African rock art treasures revealed in the Lovo Massif

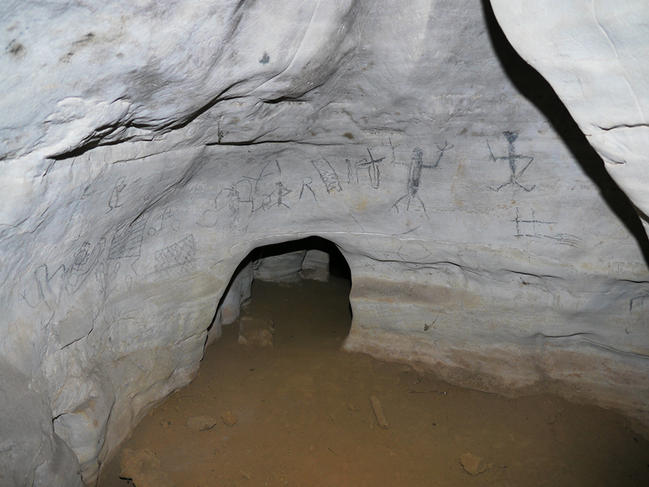

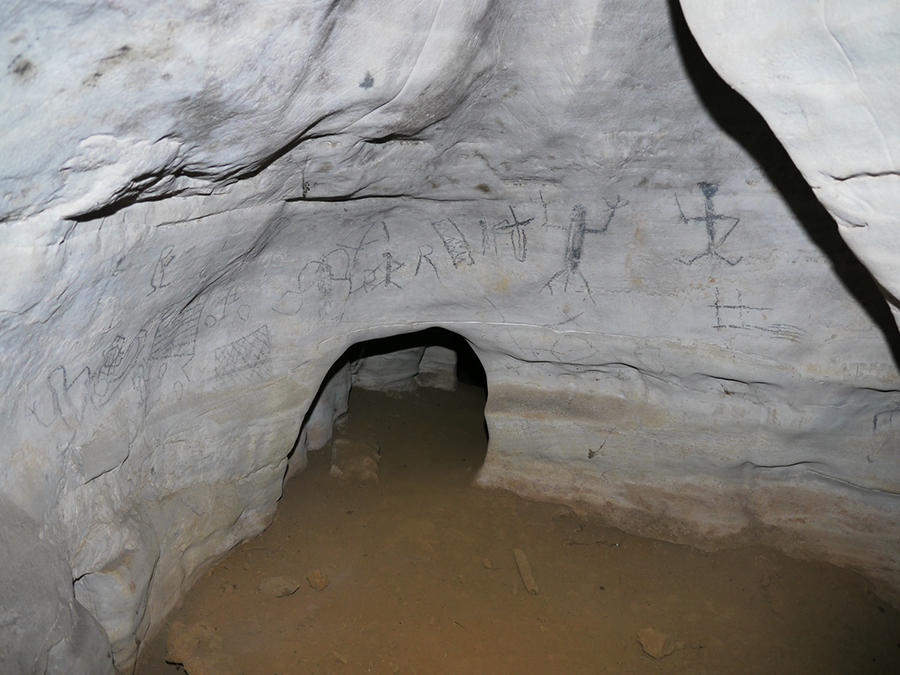

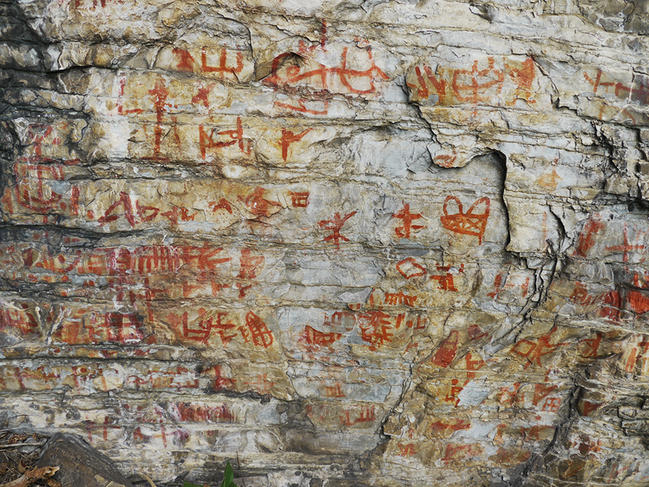

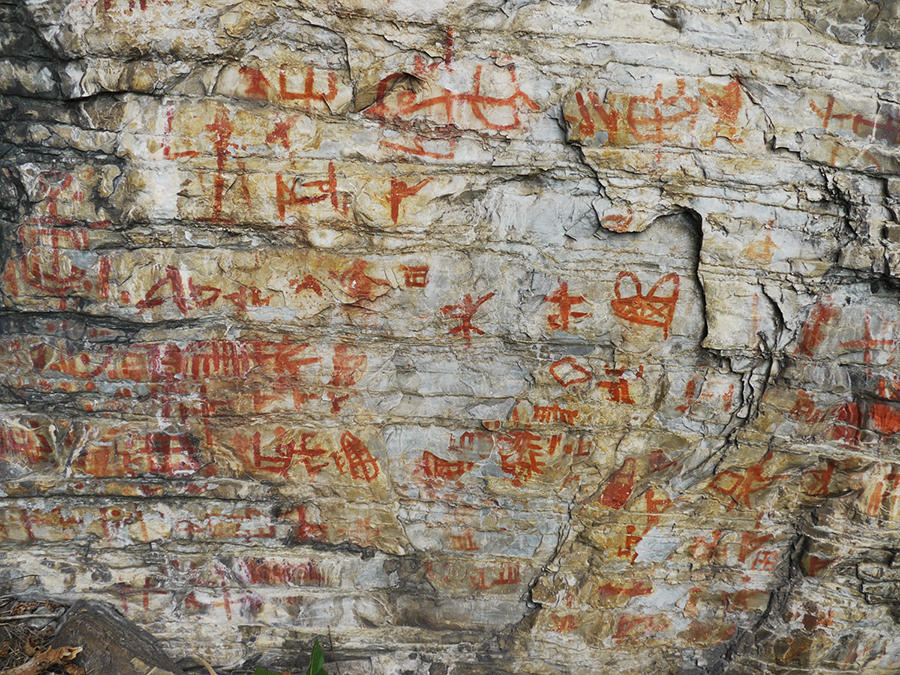

Seen from the air, the landscape is impressive. Vast limestone outcrops, looking for all the world like a ruined city emerging from the lush vegetation, stretch as far as the eye can see. But it is deep down in the clefts between the crags that lie the rock art treasures of the Lovo Massif, in the far west of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): more than a hundred caves and rock faces adorned with geometrical shapes such as crosses, circles and grid patterns, together with lizards and antelopes, figures bearing arrows and guns, and mythical creatures whose origins remain a mystery.

For over ten years now, the archaeologist and historian Geoffroy Heimlich, a researcher affiliated to the African Worlds Institute (IMAF),1 and Clément Mambu Nsangathi, deputy chief curator at the institute of national museums of the Congo, IMNC, have been attempting to shed light on this exceptional rock art site. Initially held back by the difficulties of working in a country at war and by the challenges inherent to the terrain, the French-Congolese Lovo archaeological mission, headed by Heimlich, has now shifted into top gear and is doing everything it can to fill in the gaps in our knowledge of the site.

Datings spanning several centuries

The first point to be elucidated concerns the precise dating of the paintings. With help from the Musées de France research and restoration centre (C2RMF), Heimlich has shown that seven paintings can be directly related to the period between 1480 and 1800, thus providing evidence that they are contemporaneous with the Kongo kingdom. The latter, which extended as far as present-day Angola, reached its peak between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries. Another dating carried out in the same mountain range reveals art from earlier times, between the seventh and ninth centuries.

This data will be supplemented with joint work by two researchers from the LSCE,2 the geophysicist Edwige Pons-Branchu, and Hélène Valladas, known in particular for her research into Palaeolithic rock art. The goal is to analyse samples of the thin film of calcite covering the red paintings, relying on both uranium-thorium and carbon-14 dating methods. The uranium-thorium technique is a recent development first used in archaeology some ten years ago, and is borrowed from climatology, where it helps to date stalagmites and corals. “The older the samples, the easier it is to date them, since the uranium that has decayed into thorium leaves more traces in the rock,” Pons-Branchu explains. This technically complex operation is performed using a plasma source mass spectrometer.

117 sites already identified

A second unknown quantity is the number of these sites, which are scattered over an immense, sparsely-populated region. The seven missions carried out between 2007 and 2019 identified 117 of them, of which over half were discovered by the French-Congolese team. This was only made possible with the help of the local population: paintings and engravings are hidden in river beds, at the foot of cliffs, and in hard-to-reach locations deep inside the rocks. “It can sometimes take up to half a day to clear a way through tall, dense vegetation to get to a cave or a site,” Heimlich says.

The young scientist hopes to draw up an exhaustive inventory of these caves and sites, something that requires significant resources. Following an initial aerial photogrammetry survey in 2019, a second one, hopefully in the autumn of 2021, will complete the picture by covering the entire massif, an area of some 430 km2. Analysis of these images should make it possible to “understand how the rock art sites relate to the other identified archaeological places of interest, such as ancient villages, metalworking areas, and so on”, writes the researcher in a book published last February.3 By interpreting the data, the team should gain access to as yet unidentified sites. The most promising ones will be explored on foot, before archaeological surveys or even extensive excavations are carried out.

Sites partly used for religious ceremonies

A third mystery to be unravelled concerns the purpose of the sites. Heimlich is now convinced that the rock art “was a feature of the rituals of the Kongo kingdom, which had pre-Christian origins”. The fact that the cross is frequently present in the paintings is highly significant in this regard. “At the crossroads of Kongo and Christian religious traditions, (…) this symbol was equally important in both worlds,” writes the researcher, who believes it is “very likely” that at least some of the Lovo Massif’s rock art was related to ritual ceremonies such as the kimpasi.

The latter was held “when the community felt the need to remedy the ills afflicting it”. The main rite consisted in a religious initiation ceremony in which participants were designated to be put to death and then, possessed by the nkita spirits, brought back to life in the sacred chamber.

In this multi-faceted investigation, the archaeologist, whose many skills include combining different disciplines, wants to go further and interview tribal chiefs “in order to understand the links and interactions between the paintings, the myths, and the life of the Kongo people today”.

Although the picture is still incomplete, the data when put together perfects and even expands our knowledge of this part of the world, showing that rock art in central Africa, totally neglected by research in the past forty years, makes an important contribution to the continent’s history.

A heritage in danger

Could petroglyphs be a new source for historians of Africa? This, in any case, is Heimlich’s view, following in the footsteps of one of his mentors, Jean-Loïc Le Quellec, CNRS senior researcher emeritus. In a continent where rock art has been neglected for too long, this kind of work is valuable because it can “provide historians with first-rate information, in the same way as documented material and oral traditions”, Le Quellec believes.

This heritage to be discovered also highlights the need for passing on knowledge. Given that the entire DRC has only one professional archaeologist, this is a huge challenge. In 2016, the first field operation supported by France’s Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs enabled Heimlich to train three young researchers from the IMNC and the University of Kinshasa as part of their post-graduate studies, with the Lovo Massif as their training ground. With help from the French Ministry of Culture, he also designed an accessible and stimulating e-learning module.4 A travelling exhibition, available online,5 of a selection from among the 5 700 photographs of rock art taken in the course of the various missions is due to be inaugurated in September at the National Museum of DRC in Kinshasa.

However, these efforts would be pointless without stringent protection of the sites. Unfortunately, things seem to be moving in the opposite direction, since the region’s rich underground resources have whetted the appetite of the cement industry. And the destruction has already started. “We are extremely worried. The Mbafu cave at the village of Kiangu, for example, was completely destroyed by a company. If we aren’t careful, there is a risk that many others, perhaps all of them, will eventually be lost,” explains Professor Paul Bakua-Lufu Badibanga, the director general of the IMNC, an institution fully committed to the French-Congolese mission.

The DRC is now banking on protection from UNESCO to protect this priceless heritage. The process is underway, with the very active assistance of the French-Congolese mission.

A World Heritage listing would also correct an imbalance. Although at first sight, listed sites appear to be fairly well disseminated throughout Africa, Le Quellec took a closer look at their distribution, which “reveals a surprising contradiction”, he says. It turns out that those related to natural heritage are concentrated in the eastern-central region of the continent, while cultural sites are mainly found in North Africa. Wide-ranging research like that carried out by Heimlich should help to redress the balance.

- 1. CNRS / Université Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne / IRD / EHESS / Aix-Marseille Université. Geoffroy Heimlich is also a visiting researcher at the Local Heritage, Environment and Globalisation Joint Research Unit (PALOC – IRD / MNHN), and at the Rock Art Research Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (South Africa).

- 2. Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement (CNRS / CEA / UVSQ / IPSL).

- 3. Art rupestre et patrimoine mondial en Afrique subsaharienne (“Rock art and world heritage in sub-Saharan Africa” – in French), Geoffroy Heimlich (coord.), Hémisphères / Maisonneuve & Larose Ed., coll. “Patrimoines africains”, February 2021, 322 p.

- 4. https://www.e-patrimoines.org/patrimoine/module-14-arts-rupestres-en-afr...

- 5. https://exposition-lovo.com

Explore more

Author

Brigitte Perucca is a former director of communications of the CNRS.