You are here

Sacrificing land to oil

Although petroleum and its derivative products have enabled the development of our current way of life, the activity of refineries and petrochemical plants is harmful to ecosystems and landscapes and has long-term effects on human health. In a book that they edited, Vivre et Lutter dans un Monde Toxique , Gwenola Le Naour and Renaud Bécot reveal the damage caused by what they call the “petrolisation” of our planet. To illustrate their point, they compiled a number of studies conducted in France and other countries. Their analysis turns out to be more relevant than ever, given that the hydrocarbon society is still going strong: oil consumption reached an all-time record in 2023, averaging more than 100 million barrels per day.

Your book is based on what you call the ‘petrolisation’ of the planet. What exactly does this term encompass?

Gwenola Le Naour1: In the 1960s, petroleum came to be considered a wonderful energy source, enabling the manufacture of products like plastics, synthetic fabrics, paints, cosmetics and pesticides, revolutionising our lifestyles and greatly increasing agricultural yields. The term ‘petrolisation’ refers to the transformation of our energy systems, with hydrocarbons becoming the norm all over the globe, literally transforming the physical and mental landscape.

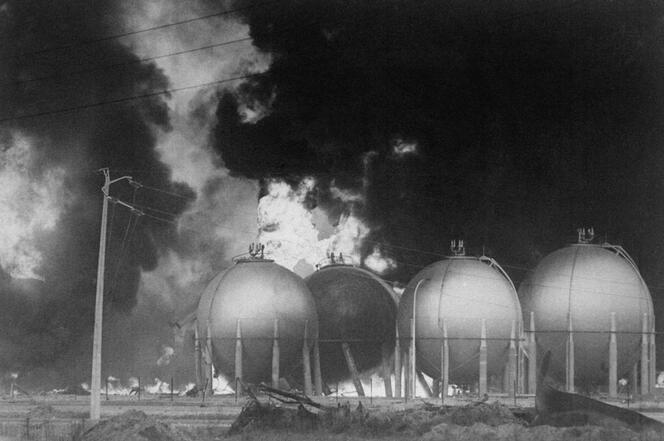

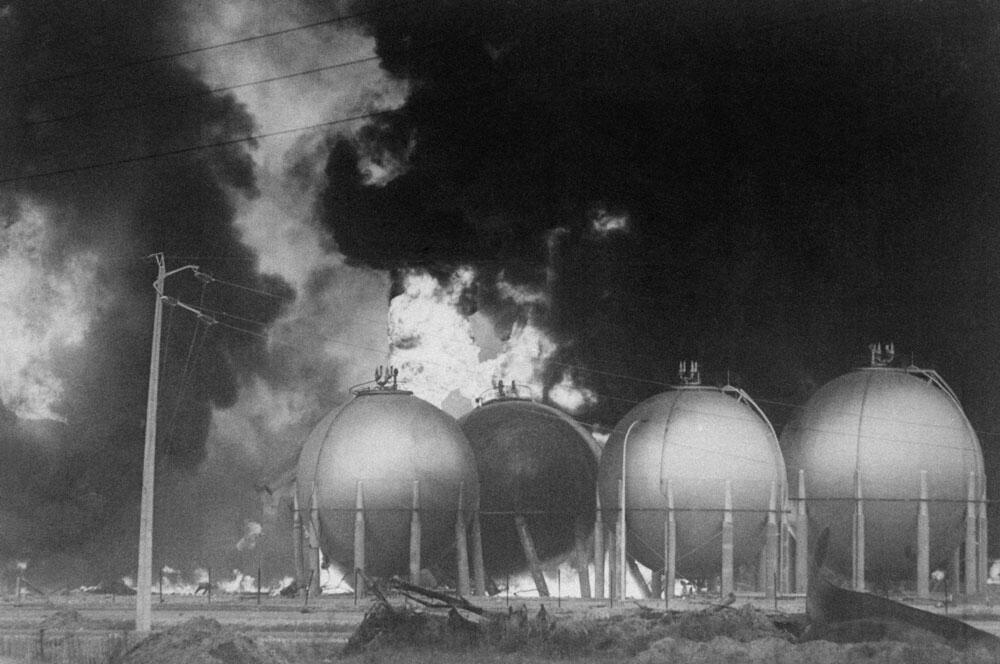

The advent of petroleum and its derivatives is most often presented as a success story, a high point in history. People tend to ignore the dark side of petrolisation, the sacrificed areas like Fos-sur-Mer (southeastern France), which since 1965 has been home to a sprawling refinery that accounts for 10% of France’s current oil refining capacity. Another example is Taranto in southern Italy, where a refinery, a petrochemical plant, a commercial port, an industrial landfill and Europe’s largest steel mill all operate side by side.

How could entire regions be abandoned to oil?

Renaud Bécot2: Petroleum and hydrocarbon production is an industry unlike any other. Oil companies have widely been supported by national governments. As with nuclear power, the history of the petroleum industry is closely linked to that of countries’ energy strategies and the way they conceive their energy independence. The French state has actively supported these installations as drivers of economic growth and wealth. However, the establishment of these industries was not without resistance, despite all the accompanying rhetoric about ‘progress’.

So there were protests to the building of these complexes?

G. LN.: From the start, local populations, as well as some elected officials, understood the impact that these gigantic installations would have on their environment. The protests failed in Fos-sur-Mer and south of Lyon, where the construction of the Feyzin refinery and a whole petrochemical complex (France’s famous ‘chemical corridor’) obliterated farmland and the ox-bows of the Rhône… But some of these actions succeeded: another plan for a refinery, to be built in the Beaujolais region (also in southeastern France), had to be abandoned. On the other hand, it is more difficult to resist once these complexes are erected, because the installation of this type of infrastructure is virtually irreversible. In the event of closure, the cost of decontamination is colossal, and results are not guaranteed.

The locals living near these facilities ultimately learn to live with it… Partly because they have no choice, but also because the industries have made an effort to operate as ‘good neighbours’, starting in the 1960s and 1970s and up to the present day. They mitigate their presence by financing cultural and sports infrastructures, for example. Not to mention the eternal dilemma between the negative impact of these industries and the jobs they create. In the book, we describe these deals made on the scale of the petrochemical zone as ‘territorialised Fordist compromises’.

What does the term ‘compromise’ mean here?

R. B.: In exchange for the seizure of land by the industry and the array of negative effects that comes with it, local communities receive return benefits that amount to a partial redistribution of the industry’s profits. This redistribution can be on a regular basis (like the business tax contributed to municipalities until 2010) or a one-time payment, following an accident for example. After a spectacular gas leak in 1989 that impacted residents living near the Lubrizol plant in Normandy, the company paid 100,000 francs to the city government of Petit-Quevilly to plant 80 trees in the town…

Yet this type of compromise has also been highly favourable to the industries, either qualifying them for long-term tax breaks – as in Sicily near Syracuse, home to one of the largest chemical and petrochemical sites, with a workforce of more than 7,000 employees – or even exempting them from tax, as in Louisiana on the banks of the Mississippi. From the 1950s through the 1980s, no fewer than 5,000 corporations in the US (mostly petrochemical, metallurgical, oil and gas companies) applied for such tax exemptions, including some of the country’s most profitable groups, like DuPont, Shell Oil and Exxon.

These practices, which developed primarily during the expansion phases of the petrochemical sector, make it more difficult to relocate these pollution-generating industries. The regions in question continue to believe that they benefit from the situation, even though this is less and less true.

Regarding the petroleum industry, not unlike nuclear power, it is often said that accidents are rare and should not be used to vilify an entire industry. Is this really the case?

G. LN.: We remember accidents like explosions – such as the one at the Feyzin refinery in 1966, which killed 18 people, or that of a stockpile of ammonium nitrate at the AZF fertiliser plant in Toulouse (southwestern France) in 2001, which caused 31 deaths – because they are few and far between. But if we look at the entire hydrocarbon chain, incidents and accidents, sometimes serious or even fatal for the employees, are actually frequent, even though they are rarely reported beyond the local media (leaks, explosions, fires, etc.). Not to mention the list of problems caused by the daily operations of these industries, such as air and water pollution, and their impact on health.

To describe the harmful effects of petrochemical industries, particularly on health, you use the term ‘slow violence’. Why this choice of expression?

G. LN.: This phrase, coined by the American author Rob Nixon, denotes gradual violence spread out over time, a characteristic of the fossil fuel economy. This violence is also inegalitarian because it mainly affects already vulnerable populations: I’m thinking in particular of the African-American populations of Louisiana whose previous generations were slaves on the plantations…

Beyond this particularly striking example, it is common for these industries to operate near working-class or poverty-stricken areas. People like to say that we all breathe the same polluted air, but it’s not actually true – some of us breathe more polluted air than others. And those who live in zones devoted to hydrocarbons have a much lower quality of life than those who are spared the proximity of these industries.

Since when has the harmful nature of these industries been documented?

G. LN.: For a long time, the only available toxicity measurements were carried out by the manufacturers themselves, based on the thresholds set by regulations. However, as those who practise it readily admit, toxicology is a very imperfect science. Regulatory toxicology does not take ‘cocktail effects’ into account, nor the consequences of repeated exposure to low doses over the long term. In addition, setting thresholds is a double-edged sword: toxicological analyses can be cited in an effort to protect people and the environment, or to justify the continuation of production processes that expose humans, animals and nature to hazardous substances. The thresholds can be presented alternately as toxicity thresholds or tolerance thresholds… In this sense, toxicology results in imperceptibility.

R. B.: Nonetheless, alternative studies have started to emerge, using original methodologies. In Canada, a participatory survey was conducted in the 2010s on the land of the First Nations in Ontario and Saskatchewan, thanks to an unprecedented partnership between a research team and a collective of investigative reporters. Through the widespread distribution of inexpensive, easy-to-use measurement kits, it showed that the populations were exposed to hydrogen sulphide, a toxic gas that penetrates through the respiratory tract. This participatory approach made it possible to obtain changes in regulations and improved pollution monitoring – a genuine victory that has changed people’s lives, even though the industry has not been relocated.

What about the health effects of all these pollutants? Are they documented?

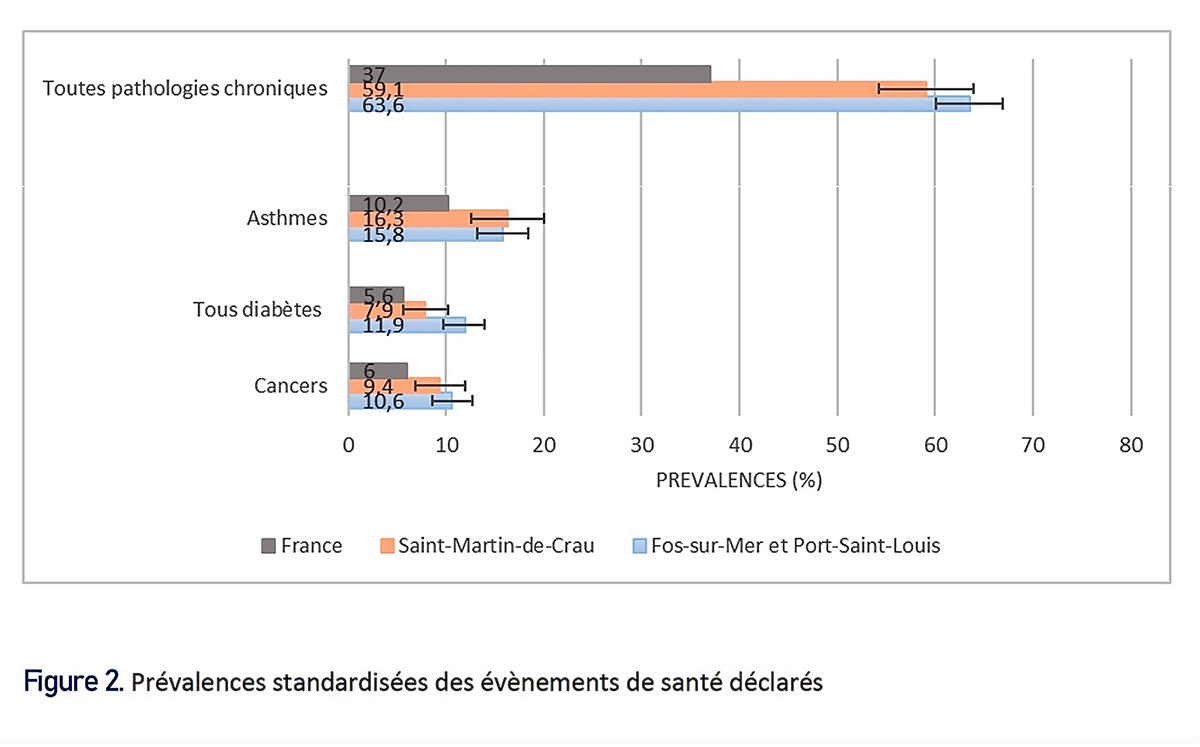

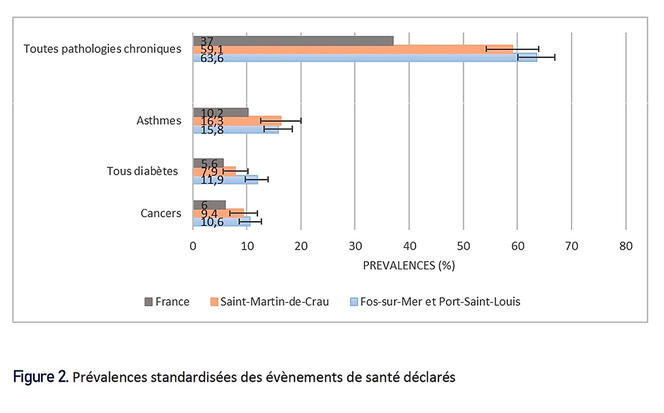

G. LN.: In France, the only investigations carried out so far have been on the Lacq natural gas field in the Pyrenees, which was in operation from 1957 to 2013. The first academic study, conducted in 2002, concluded that there was an increased risk of cancer in the area. Two other surveys were launched more recently: a mortality analysis in 2021, which revealed a higher prevalence of cancer deaths, and a morbidity review that is still in progress. In Fos-sur-Mer, the ‘Fos Epseal’ study, conducted between 2015 and 20223, was based on health problems reported by residents. Its findings show that nearly two-thirds of the population suffers from at least one chronic disease – asthma, diabetes – as well as a year-round nose-throat irritation that had not previously been identified.

R. B.: One point emphasised by communities that report health issues linked to the petrochemical industry – chronic ENT diseases, diabetes, cancers, especially paediatric cancers, etc. – is the difficulty of formally establishing a correlation between these conditions and a given toxic exposure.

In any case, such a link could not be proved by conventional epidemiology, which works on large scales with large numbers and is ill-suited for deployment in smaller geographic areas. This is why the activist groups and the scientists who work with them need to be inventive, sometimes calling upon the human and social sciences, with sociologists gathering testimonies and exposure trajectories, historians documenting the history of the production sites, etc.

Proving a correlation also means developing technologies and tools to measure how and when people are exposed. Lastly, it requires long-term cooperation among activist groups, the populations and researchers from multiple disciplines. The aim is to define new protocols for better documenting the negative effects on health and the environment, with the active participation of the women and men who experience exposure in the flesh. ♦

For further reading

Vivre et Lutter dans un Monde Toxique. Violence environnementale et santé à l'âge du pétrole (“Living and Struggling in a Toxic World. Environmental violence and health in the Petroleum Age”. In French), Renaud Bécot and Gwenola Le Naour (eds.), Seuil, “Anthropocène” collection, September 2023, 480 p.

- 1. HDR senior lecturer in political science at Sciences Po Lyon and researcher at Triangle: Action, Discours, Pensée Politique et Économique (CNRS / ENS Lyon / Sciences Po Lyon / Université Lumière Lyon 2).

- 2. Senior lecturer in contemporary history at Sciences Po Grenoble, member of the PACTE social sciences laboratory (CNRS / Université Grenoble-Alpes).

- 3. Participatory study in environmental health, focusing locally on the industrial complex of Fos-sur-Mer and Port-Saint-Louis-du-Rhône.

Explore more

Author

Brigitte Perucca is a former director of communications of the CNRS.