You are here

Writers know no frontiers

Under what circumstances was PEN founded nearly 100 years ago?

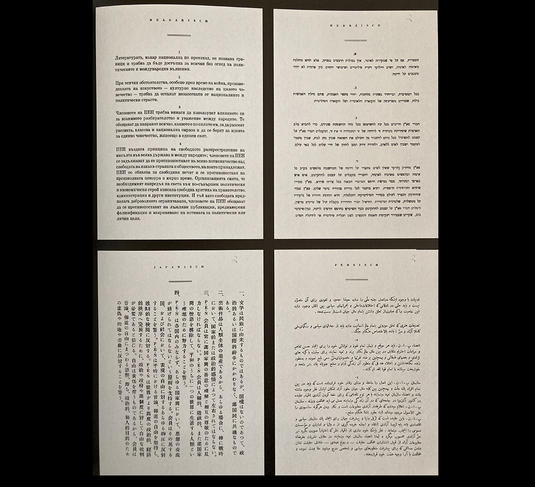

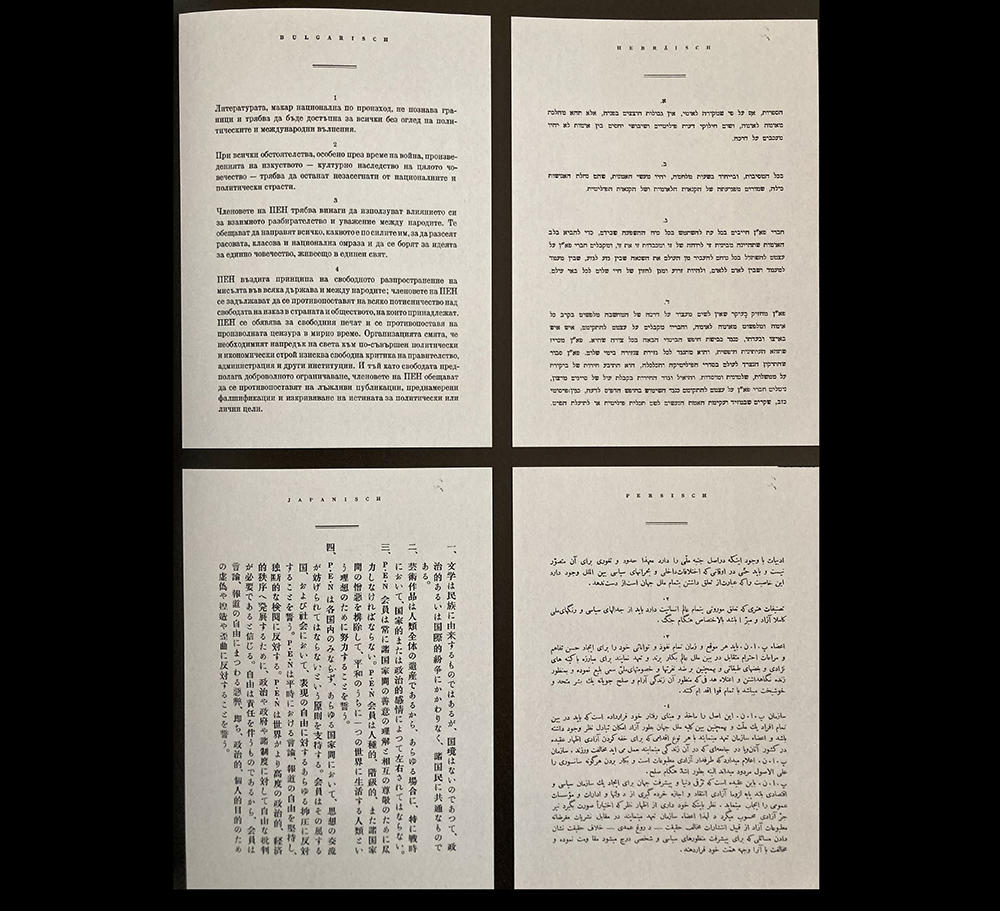

Laetitia Zecchini:1 PEN, whose three letters originally stood for ‘Poets, Essayists, Novelists’, but which now also includes translators, publishers, journalists, bloggers, etc. – in other words, women and men who are contributing to the promotion of literature, in the broadest sense of the term – was founded in London in 1921 upon the initiative of the British feminist writer Catharine Amy Dawson Scott. It was first launched as a ‘club’ through which writers could meet, before becoming an ideal of community and friendship born of the trauma of World War I and the pacifist movement of the interwar period. The idealism of the PEN founders, whose goal was to promote peace and reconciliation among peoples by facilitating the free circulation of written works, along with mutual understanding among writers worldwide, is reflected in the founding principles of the charter adopted in 1927. Article I stipulates that ‘Literature, national though it be in origin, knows no frontiers and must remain common currency among nations in spite of political or international upheavals.’ This article would remain unchanged until 2003, when the expression ‘national though it be in origin’ was deleted and ‘among nations’ replaced by ‘among people’.

Were PEN Clubs soon blossoming outside of Europe?

L.Z.: Yes – PEN quickly sought to expand its membership rolls outside of Europe, uniting writers beyond the borders of their own countries in a community conceived to be truly global. The first non-European PEN was founded in Mexico City in 1923, followed in the 1920s and 30s by other centres in Johannesburg, Buenos Aires, Peking Beijing, Bagdad, Bombay Mumbai, Tokyo… Every year PEN holds its annual congress in a different city around the world, illustrating the organisation’s internationalist, federating ideals.

In the 1930s, how did PEN react to the rise of the extreme right in Germany, Italy and Spain?

L.Z.: First of all, I should emphasise that the organisation has always been ready to adapt and redefine its mission, and has always seen debates and contentions, sometimes quite heated, on the nature and limits of literature, freedom of expression, politics and activism. Originally, PEN took an apolitical stance as a matter of principle. Later, the rise of fascism and Nazism forced it to adopt a clearer position and distance itself from the apolitical idealism of its early years. The centennial book includes a deeply moving document: a speech given by the German Jewish communist writer Ernst Toller at the PEN congress in Dubrovnik (Croatia, formerly Yugoslavia) in 1933. Speaking on behalf of all the writers in exile, all those who no longer had a voice, he denounced the book burnings in Germany, the persecution of authors, naming them one by one, and more generally the fanatic nationalism and ‘brutal racial hatred’ that had taken hold within the German PEN centre, from which Toller had been expelled. In fact, the Nazification of PEN Germany led to the centre’s exclusion from the organisation a few months later. PEN’s principles were no longer compatible with a totalitarian government. The organisation’s role was to protect writers who were victims of tyranny, not those who inflicted it. This was a position from which it would never waver, and that became further entrenched during the Cold War. This is the core of PEN’s mission: to defend and support those oppressed by terror and censorship, a category that has included Jewish writers in Nazi Germany, Boris Pasternak in Soviet Russia, Wole Soyinka in Nigeria, Ángel Cuadra in Cuba, Mahvash Sabet in Iran, Asli Erdogan in Turkey, and so many others, famous or less famous.

How does PEN help writers who have had to flee their countries?

L.Z.: First of all through its ‘Writers in Exile’ centres. The first one, founded in 1934 and based in London, brought together German writers who had fled Nazism. Over the years many other such centres have provided aid to authors from Vietnam, China, Iran, Cuba, North Korea, Xinjiang (Uyghurs), Eritrea, etc. These centres operate as mutual assistance networks, uniting displaced writers and coordinating the material and editorial support they receive, which includes the translation and promotion of their work. The exile centres also serve as forums and platforms for writers to denounce repression in their home countries. In 2006 the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN) was founded to offer shelter for exiled writers. Today it includes more than 70 cities around the world.

PEN has demanded the release of many imprisoned writers. Who was the first?

L.Z.: The Haitian poet Jacques Roumain, imprisoned in the mid-1930s for his opposition to the American occupation of his country. Every year since 1960, PEN has published a Case List of violations committed against writers. Similarly, at certain PEN meetings an empty chair is placed at the front of the stage for an author deprived of freedom to preside symbolically over the session. This ritual is a means of resisting the efforts of repressive governments to silence certain writers and blot out their memory. As explained by Marian Botsford Fraser, former chairwoman of the PEN Writers in Prison Committee, PEN is first of all an organisation made up of writers who ‘work for other writers. The worst thing that could happen to us is that we become faceless statistics, forgotten prisoners’. Solidarity is a cornerstone of the association. Starting in the 1960s, PEN centres the world over have made imprisoned authors in other countries honorary members, pledging to support them until their release.

It is also remarkable that many writers defended by PEN, once they are released or allowed back in their country, become actively involved in the organisation, using their reputation and high profile to benefit lesser-known contemporaries. I could mention Indian-born Salman Rushdie, who became president of PEN America after he came out of hiding, or Svetlana Alexievich, who became president of PEN Belarus.

Why does PEN attach so much importance to protecting linguistic diversity?

L.Z.: From the very beginning, PEN has sought to promote better understanding between peoples and cultures. This cannot be accomplished without respecting and even encouraging differences, including linguistic differences. Furthermore, while freedom of expression and literature are inseparable, so is the former from linguistic freedom, the right to write, to publish and to be recognised in one’s own language. And this right goes hand-in-hand with the promotion of translation. ‘Minority’ languages are not so much minor as they are trivialised or marginalised, in particular due to limited access to translation. PEN stipulates that all literature and all languages are of equal value. The organisation played a crucial role, with the support of UNESCO, in the drafting in 1996 of the Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights,2 which helped establish the concept of ‘linguistic community’.

In 2021, is PEN still effective in giving writers the ability to write, publish and read freely?

L.Z.: Today PEN coordinates the activities of more than 145 centres across the globe and includes about 20,000 members. But it is not always easy to demonstrate an organisation’s effectiveness. For example, what induces a government to release a writer? There are many different factors and people involved, without any doubt. And we must bear in mind that much of PEN’s activism takes place behind the scenes. Its successive presidents and secretaries emphasise the power of the organisation – which can mobilise all the living laureates of the Nobel prize in literature and the presidents of PEN centres worldwide, plus its networks with other NGOs and the United Nations (with which PEN holds consultative status) – as well as its fragility. PEN has of course had its share of terrible setbacks, like the execution of the Nigerian writer Ken Saro-Wiwa in 1995, and the long captivity and subsequent death of the Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo. But to answer your question more directly, concerning the organisation’s missions and the many authors for whom PEN has tirelessly campaigned, I would say yes, definitely. Without PEN, freedom of expression would be more fragile and many writers around the world would be even more isolated and vulnerable.

Would you say that the book you have co-written proves that literature is nearly always a central element in the mechanisms of power?

L.Z.: Absolutely. The book shows the extent to which literature is at the centre of the world’s upheavals and the issues of power and surveillance. It has never been an isolated realm, ‘superfluous’, ‘innocuous’ or considered as such. This is something that all authoritarian regimes have understood. The threats that have constantly been directed at writers the world over show the extent to which literature always has a political dimension, is political in itself. In a sense, repression and censorship retroactively confirm the power of words, the power of literature.

To find out more about PEN: https://pen-international.org/fr

For further reading PEN International. An Illustrated History, C. Torner, J. Martens, G. Avalle, J. Clement, P. McDonald, R. Potter and L. Zecchini, Thames & Hudson, 2021. Pen International. Une Histoire Illustrée, Actes Sud (coll. Beaux-Arts), 2021. The book was recently awarded the Kiran and Pramod Kappor Prize for Best Book of the Year at the Frankfurt Book Fair.

Viewing An introductory video about the book, in English with French and Spanish subtitles: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pdm_jKLNgu4

Explore more

Author

Philippe Testard-Vaillant is a journalist. He lives and works in south-eastern France. He has also authored and co-authored several books, including Le Guide du Paris savant (Paris: Belin) and Mon corps, la première merveille du monde (Paris: JC Lattès).