You are here

What are the universal translators of science fiction worth?

Whether it be omniscient robots, pills and microbes to be ingested, and even "miraculous" fish, science fiction is rife with astonishing universal translation systems. The famous Babel fish imagined by the writer Douglas Adams in the Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (1979) can be inserted into one's ear to understand any language heard. Just as the "computer-translator pill" thought up by Stanislas Lem in The Futurological Congress (from the Memoirs of Ijon Tichy) (1976) is effective upon absorption: "The buzzing sounds surrounding me instantly transformed into perfectly intelligible words in my ears." Not to mention the translating microbes from the Australian-American TV series Farscape (1999), which can be injected to understand foreign languages. Sadly, the progress made by nanotechnology, biotechnology, information technology, and cognitive science (NBIC) has not yet allowed such far-fetched solutions to materialise.

When it comes to robots — and therefore to computer science — Robby from the film Forbidden Planet (1956) is impressive: "if you do not speak English, I can help with 188 languages." In Return of the Jedi (1983), C-3PO brags about knowing 6 million forms of communication, hence being able to translate from one to the other. This involves translating between two known languages; while films do not explain how the robots achieve this, the performance seems plausible.

In the book Epigone: History of the Future Century (1659), Abbot Michel de Pure describes a sort of altar beneath a crystal dome equipped with a mouthpiece. Whenever someone talks into the mouthpiece, the main character Epigone can understand what they say. This communication with the unknown — whether extraterrestrials or foreigners — is the primary application of universal translation in Sci-Fi, well before its emergence in the harsh reality of the Cold War.

Epigone is also an example of the most complex scenario, namely translation from a totally strange source language into a familiar tongue with no Rosetta Stone to help, thereby raising questions regarding its plausibility.

This is also the case in Murray Leinster's trailblazing short story First Contact (1945), not to be confused with the film Arrival directed by Denis Villeneuve released in 2016. It depicts extraterrestrials communicating with humans via electromagnetic waves and developing an artificial code that acts as an intermediary, which is referred to as an interlanguage or interlingua, and is not strictly speaking a language.1 Two translations are thus needed for each exchange, for instance from the alien tongue into the artificial code, and from the artificial code into human language.

This code uses symbols to designate objects in the world, as well as diagrams and images to indicate the relations between symbols. This universal translator, which is possibly the first to appear in modern Sci-Fi, is referred to as an encoding-decoding machine. It does not involve a computer language, but an actual intermediary conceived to facilitate communication, exactly like the mechanical idiom "mechaneseFermerFictional artificial language imposed on a human in the book Star Child (Frederik Pohl and Jack Williamson, 1965) to enable communication with an all-powerful machine." detailed in Star Child, halfway between the expressive capacities of humans and machines and created to enable more effective communication between them.

Is this approach of interest for creating real machine translation? Scientists have wondered at one stage whether systems that systematically use an interlanguage provide greater effectiveness and flexibility with respect to the languages to be translated.

Research explored an interlingua conserving the essential principles of languages (dictionary, grammar), while using abstraction to leave aside the distinctive features of each one. The term Interlingual Machine Translation is used, and it appears that science and science fiction are following the same path. This is true broadly speaking, for researchers are not drawing inspiration from mechanese, or from the universal numerical codes of Descartes and Leibniz, but instead have innovated with computer science methods, and later with the massive introduction of statistics.

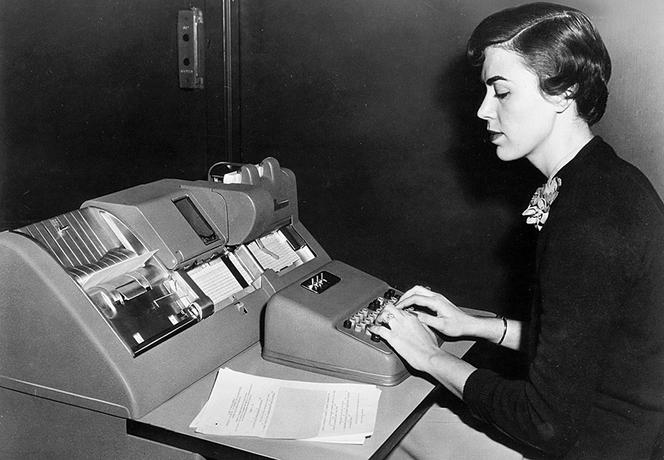

Processing occurs at the level of the sentence, and takes context into consideration; it is also based on huge amounts of examples and is much more effective than "word-for-word translation", whose limitations have long been obvious. This is especially true with respect to the first computer science program — the "brain" — which was developed in 1954 by IBM and Georgetown University in order to translate about sixty sentences from Russian into American English. This method requires no more than a simple bilingual dictionary, but it stumbles each time there is ambiguity, which is to say in practically every sentence.2

In practice, the more data on languages is available (one can speak of big data), the better the translation. By contrast, translating from or into an idiom that is not highly delineated proves difficult. In the end it is a widely-used tongue, English, that often plays the role of interlanguage, in which case the term pivot language is used.

With the advent of deep learningFermerA machine learning technique in artificial intelligence (AI) that uses neural networks (mathematical functions). They can extract/analyse/sort out the abstract characteristics of the data they are presented, without the explicit production of rules. How the system arrives at the result remains a mystery; it is a "black box." The symbolic route, which is the other major approach used in AI, uses perfectly clear logical rules drafted by human programmers ("transparent box"). in artificial intelligence (AI), current research is exploring numerous avenues that seek to minimise human intervention. Nobody is building interlanguages anymore, and the development of multilingual learning methods has led to the circumvention of pivot languages. By contrast, deep learning has raised new questions. It is worth noting that in this approach, which is based on neural networks, the machine learns to analyse a text in its own way (based on vectors and mathematical operations), one that was not dictated in a series of rules drafted by a human programmer.

The machine therefore constructs its own representations. It is tempting to see this as the materialisation of a kind of interlingua, for instance in the hidden layers of Google Translate (Google Neural Machine Translation). This "interlanguage" could even be studied as a work by a machine, and could hence be of interest due to its originality and even its universality. In reality it is no more than an internal representation, as in all deep neural networks.

What is interesting here is that Google Translate was conceived to be multilingual, and not solely dependent on pairs of two languages. This advance can be interpreted as a capacity to transfer knowledge from one pair to another, but not as the — so to speak— supernatural emergence of an interlanguage invented by a machine. In short, if reality is catching up to fiction, it is also pursuing its own paths.

The author is solely responsible for the points of view, opinions and analyses expressed in this article, which do not in any way constitute a statement of position by the CNRS

- 1. In order to be considered a "language", the system of signs must be specific to a group of individuals that use it to communicate among themselves (socio-political dimension), otherwise it is no more than some kind of code.

- 2. There is a famous example invented by machine translation researchers that is close to real examples. A system intended to translate word-for-word is given the following sentence: "The spirit is strong, but the flesh is weak". After a first translation into Russian, the sentence retranslated the other way around by the system would yield: "The vodka is good, but the meat is rotten."