You are here

The Big-brother Effect on Language Development

If you think that younger children in big families probably learn to talk faster than their older siblings, think again. When several children vie for the parents’ attention, conversation in fact often rhymes with competition—to the detriment of younger ones who, as existing studies show, will develop language skills more slowly the more older siblings they have. Yet it’s not all older siblings who pose a threat to language acquisition, a new study now importantly highlights. Using data from over 1000 French-born children to gauge the impact of older-sibling gender and age gap on children’s language development, the study singles out big brothers—and not big sisters—as the culprits in this department.1 A study that says as much about culture as it does about family interactions.

Scientists believe that early language acquisition is fostered by speech directed to children by adults, placing some at an advantage over others. “Different cultures vary in the way parents address their young children,” notes CNRS researcher Franck Ramus from the LSCP.2“In Western-country families with high socio-economic status, parents talk massively to their children. Less so when economic status is lower.”

And when it comes to big families, the trouble is that parental attention—like any other limited resource such as food or money—must be divided between children. This phenomenon captured the attention of LSCP psycholinguists when one colleague presented research on language development in a Bolivian forager-horticulturalist community in which women give birth to an average of 9 children each. “We started to discuss the effects that siblings and family composition might have on language development in all kinds of societies,” recalls Naomi Havron of the LSCP. “And we decided to begin by looking at our own society.”

The Paris-based team found statistical data close to home by turning to EDEN, an ongoing French project linking two university-hospital maternity wards (CHRU de Nancy and CHU de Poitiers) and INSERM. LSCP researcher and assistant professor of psychiatry Hugo Peyre explains that EDEN regularly follows up a group of mothers and their children born between 2003 and 2006, with the aim of “examining early determinants of the health of individuals in France, namely the environmental factors that influence child development including cognitive development.” The resulting dataset “reflects the sociodemographic characteristics of France’s general population even if socioeconomic levels here tend to be higher than average.”

From language-skills tests taken by over 1000 EDEN participants at 2, 3 and 5-6 years of age, the LSCP team developed models correlating children’s test scores with their older sibling’s gender and the age difference between them—“characteristics we thought might affect the kind of input the child gets,” Havron indicates. To avoid the blurring of effects from multiple older siblings, only children with one older sibling were considered, along with those with no older siblings.

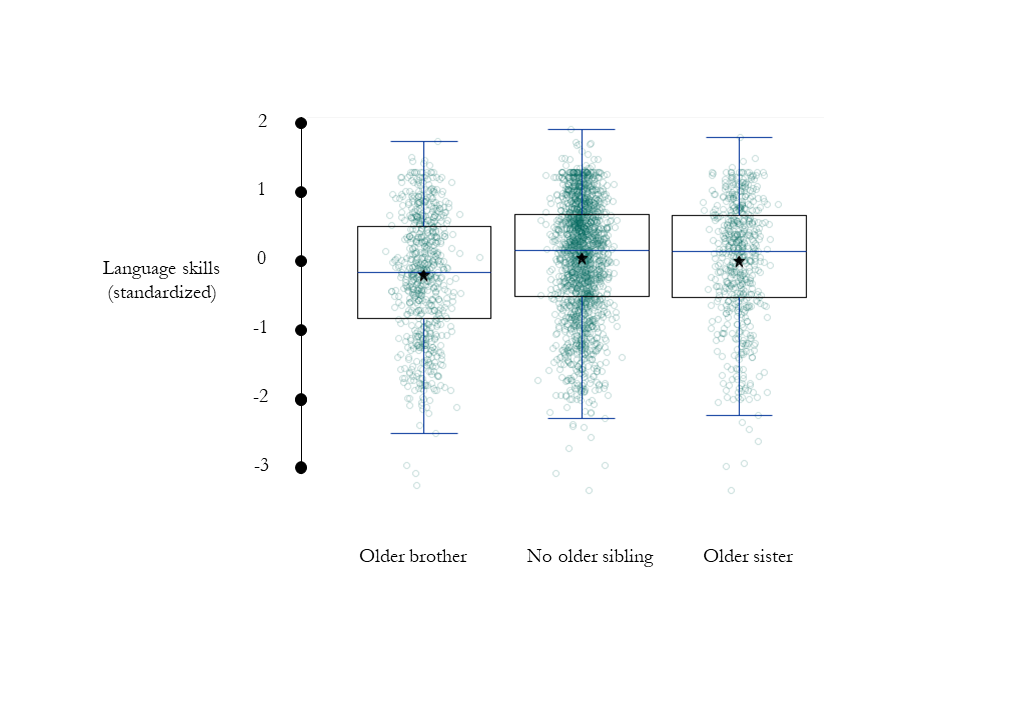

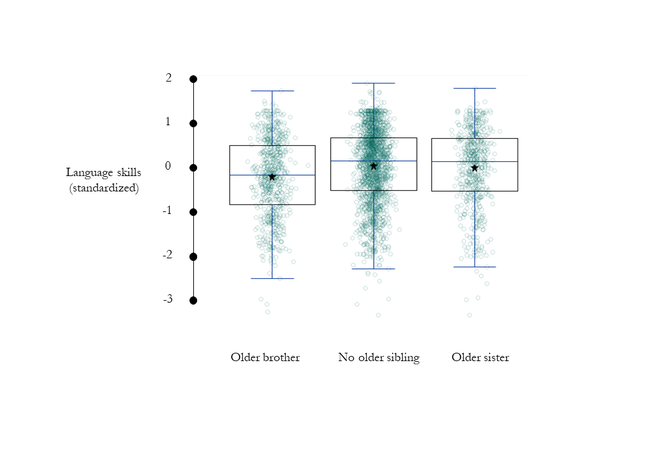

The models yielded a mix of confirmations and fresh revelations. First up, no surprises when children with an older sibling showed lesser language skills than those without one. Next, confirmation came for another hunch the team had started out with—that children with a big sister would outperform those with a big brother. So much so, it turned out, that children with older sisters scored roughly on a par with those with no older sibling. The upshot is significant: as having an older sister does no harm to a child’s language skills, it’s now clear that we are dealing specifically with an older-brother effect.

An effect that doesn’t seem to fade over time. Ramus reports that the effect “is as large at 5-6 years as at 2 years old. We have no data beyond, but it’s perfectly possible that those with an older brother never catch up and permanently keep this negative effect on their language ability.”

If big brothers hinder their younger siblings’ language skills, do big sisters on the other hand boost them, one might ask? At the study’s outset, the scientists counted on older sisters giving positive input on the grounds, firstly, that big sisters tend to act more as nurturers than big brothers, and secondly, that young girls are more linguistically advanced than boys of the same age. However, this same reasoning also led the researchers to expect far better scores in big-sister scenarios where wide age gaps exist, given that much older sisters with far stronger linguistic ability can be relied on even more heavily to care for and talk to young ones. This, however, was not the case: the models showed that kids with much older big sisters have no particular edge. Which leads the researchers to speculate that the way boys behave is also part of the equation. Ramus suggests: “Boys may demand more attention and resources from their parents, leaving less for the new baby. Also, older brothers may be more inclined to compete with younger siblings, and less inclined to talk to them than older sisters.” Hypotheses that the team hopes to “tease apart in future studies to explain the negative older-brother effect”.

Another issue calling for further scrutiny is the comparative effect of small and wide age gaps between siblings. Initially, the researchers anticipated a wide age gap to be more beneficial than a small one on the basis that two closely spaced children may compete more for parental attention. But in fact, no major divergences were recorded for differing age gaps. Havron expects that “intercultural comparisons could shed more light on this.”

For language development is largely shaped by culture, namely cultural expectations of gender roles, specifies Havron. “Imagine a society with very strict gender roles where older sisters are expected to act like little mothers while older brothers ignore their young sibling… In this society, we’d expect to see a larger difference between a child with an older sister and the one with an older brother.”

And not only can culture determine a society’s gender roles, it can also sway age-gap effects. “Imagine a 13-year-old sister with a younger sibling aged 2,” Havron continues. “In France, the older sister may be busy with school work and activities, and rarely be at home to interact with the toddler. But in a different culture she might have fewer activities and be expected to help at home more.”

Given the key influence of culture on family roles and hence family interaction, the LSCP team now aims to widen their investigations via a series of cross-cultural comparisons. Havron concludes: “We’re planning several projects to look at input from siblings and children’s language achievement in very different societies and cultures—for example by analysing actual home recordings to directly examine sibling input. Stay tuned!”

Explore more

Author

As well as contributing to the CNRSNews, Fui Lee Luk is a freelance translator for various publishing houses and websites. She has a PhD in French literature (Paris III / University of Sydney).