You are here

Oblivion, the second death of extinct species

Pollution, global warming and deforestation are just some of the factors that lead to the extinction of certain species. In a newly-published study,1 you explain how these physical occurrences are compounded by the cultural phenomenon of “social extinction”. What does that involve?

Franck Courchamp:2 Social and physical extinction take place in parallel. A species can both vanish from the surface of the Earth and be forgotten – two types of disappearance with different consequences. Social extinction plays a determining role in conservation. As a matter of comparison, if we lose sight of historical facts, we will be collectively incapable of building our future correctly by learning from our mistakes. In the same way, if we forget the species that have gone extinct, we will be less inclined to protect those that survive, since we will not be conscious enough of the threats facing our natural heritage. This concept, which is fundamental in conservation biology, is only vaguely touched on in the scientific literature. It is Ivan Jaric, a researcher at the Biology Centre of the Czech Academy of Sciences, who identified and clearly defined it.

With which species has this phenomenon been observed?

F. C.: The Japanese wolf, the okami, is an interesting example: an animal that is disappearing from human memory after having been wiped out from nature a little more than a century ago. While people in Japan know about it through a video game character, they think of it as a myth, despite the presence of a few remaining museum specimens. Another illustration is the Spix's macaw, a large blue parrot that made a glorious comeback in the animated film Rio. The local populations in its former natural habitat had no idea that it had lived in their midst before going extinct, and thought it was a bird found in the city of Rio! In addition to the species that are gone and consigned to oblivion, there are also those that are endangered and already forgotten, simply because they have never had a societal existence!

Are the members of more charismatic species less likely to be forgotten?

F. C.: Belonging to such a species, being important for society or close to humans, are among the factors that can slow an animal’s eradication from the collective memory. But that’s not enough. Being a wolf, charismatic though it may be, has not protected the okami from being forgotten. Similarly, the vast majority of people do not know that the giraffe, another popular animal, is critically endangered. The paradox of the extinction of rare and nonetheless high-value species must also be borne in mind:3 although their value should protect them, it actually puts them at risk.

Why is it important to remember these species?

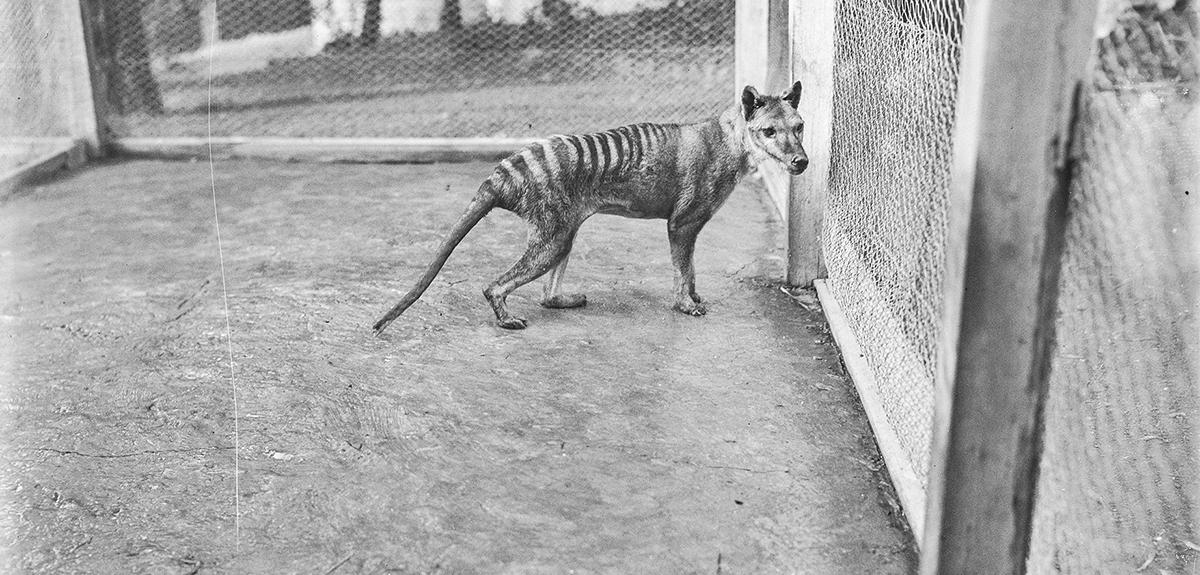

F. C.: Without the memory of past extinctions, we run the risk of not preserving biodiversity. As I mentioned before, oblivion distorts the perception of peril. The danger is that when certain species are no longer remembered, we subconsciously start to underestimate, or even doubt, the threat to ecosystem diversity, thus giving the sceptics greater credibility and importance. It is essential that we are aware of the fragility of biodiversity, the hazards that jeopardise it and the urgency of protecting it. Consequently, the memory of extinct species must remain vivid in our minds and cultures. If the people of Australia knew that the Tasmanian devil lived on the Australian mainland before going extinct there, they would no doubt be more supportive of the programmes to protect the animal in Tasmania, where its survival is now uncertain. Along with these practical considerations, I would make another point, more philosophical and no doubt even more fundamental: it is a shame to lose part of our global heritage, and this includes those species, their presence in our history and the culture surrounding them.

Such memory is often based on a concrete experience of nature, on oral transmission rather than abstract book knowledge, even though we live in an increasingly urbanised world, far removed from nature. What do you think should be done to prevent this collective memory loss?

F. C.: Nature is a source of wonder and fascination – that alone, in my view, should be sufficient motivation to learn about and protect the planet’s natural heritage. But to be fully aware of it, our societies need to reconnect with the environment. The epidemic and lockdowns we are going through show how necessary this is. How many species populate our planet? Eight million? Fifteen million? More? We don’t know the answer yet. The first leverage point in the fight against oblivion is, of course, finding out how much we don’t know. We have identified about two million species, in other words a tiny fraction of all those in existence, and many are going extinct before we even have time to describe and classify them, or understand how they are interrelated. Still, the “utilitarian value” of nature (Editor’s note: as opposed to its intrinsic value) should not be overlooked. The disappearance of certain species, botanical in particular, actually results in the loss of certain forms of knowledge, especially medicinal. We eat less than 3% of all the plants that could be farmed, thus depriving ourselves of tremendous resources. The economic cost of the threat to biodiversity is alarming… This is why we shouldn’t neglect sources of mediation, such as museums, documentaries, the Internet, etc., to help preserve living species in both their natural habitats and in our collective memory.

- 1. “Social extinction of species,” Jarić, I., Roll, U., Bonaiuto, M., Brook, B.W., Courchamp, F., Firth, J.A., Gaston, K.J., Heger, T., Jeschke, J.M., Ladle, R.J., Meinard, Y., Roberts, D.L., Sherren, K., Soga, M., Soriano-Redondo, A., Veríssimo, D. and Correia, R.A. (2022). Trends in Ecology & Evolution (15 February 2022).

- 2. Franck Courchamp is a CNRS research professor at the ESE laboratory (CNRS / Université Paris Saclay / AgroParisTech).

- 3. F. Courchamp, E. Angulo*, P. Rivalan*, R. Hall*, L. Signoret, L. Bull & Y. Meinard. 2006. “Value of rarity and species extinction: the anthropogenic Allee effect.” PLoS Biology. 4(12): e415. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040415.

Author

Brigitte Perucca is a former director of communications of the CNRS.