You are here

Indonesia: Investigating a Tsunami

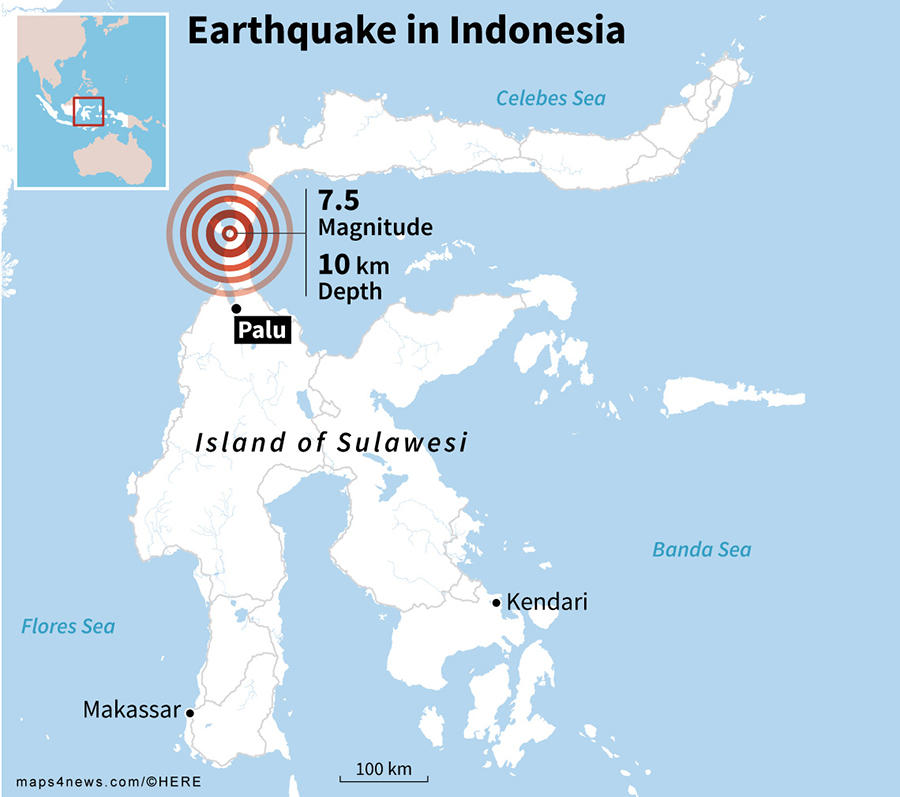

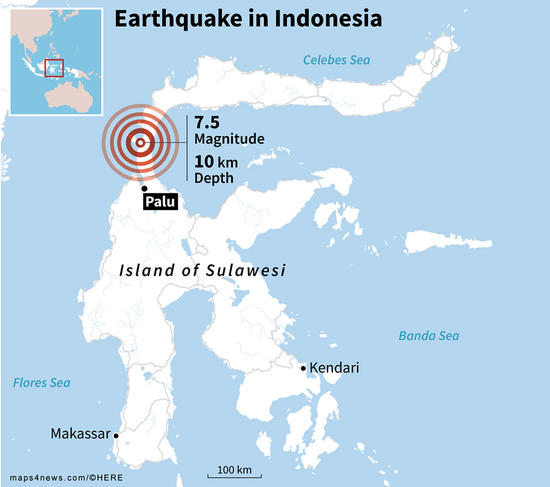

Can you remind us of the circumstances that led you and your colleague Gilles Brocard1 to go to Palu after the tsunami struck this city in Sulawesi last September? We know that affected areas are often difficult to access after such catastrophes...

Jean-Philippe Goiran:2 At the time, we were both at the northwest tip of Sumatra Island, in the Banda Aceh region. We were there taking samples of sedimentary layers, to determine whether this area, which was hit so hard by the 2004 tsunami, had experienced recurring tsunamis in preceding centuries. After the Palu earthquake of September 28, 2018, some of our fellow Indonesian geologist soon suggested that we join the international scientific mission they were preparing.3 We keenly accepted, as it gave us the rare opportunity to study the impact of a tsunami very shortly after it had struck.

What were the primary objectives of this scientific mission?

J.-P. G.: The mission focused on three primary research areas. First, geologists and civil engineers studied earthquake damage on infrastructure, in an effort to understand why certain buildings resisted, while others collapsed like a house of cards. A second group of researchers, including Gilles Brocard and myself, focused on the tsunami, and its impact on areas located near the shoreline. We used boats equipped with sonar to investigate the effect of near shore sea floor morphology on the tsunami run up distance and deposits. Finally, a third group of scientists focused on three extensive landslides that struck the city of 300,000 inhabitants and its suburbs within seconds of the main quake, causing thousands of deaths.

Indonesia regularly experiences such catastrophes. We all remember the tsunami that even more recently struck the Sunda strait, on December 22, 2018. A tsunami triggered by the collapse of a volcanic cone caused hundreds of deaths along the coasts of Java and Sumatra islands... What explains the frequency of such catastrophes in this part of the world?

J.-P. G.: Let’s start by saying that 95% of Indonesia’s volcanoes are located along the Sunda Trench subduction zone, where the edges of multiple tectonic plates meets, causing intense seismic activity. The Indian and Australian plates in particular slide beneath Indonesia at a speed of 4 to 6 cm per year. This phenomenon of subduction generates great friction between the plates, thereby triggering deep earthquakes. When this occurs at sea, it generates a sea wave that grows in amplitude as it approaches coastal areas—this is what’s known as a tsunami. Given that the Indonesian archipelago includes approximately 17,000 islands and islets, the chances of such waves submerging this vast stretch of coastline is particularly high.

What obstacles did you have to contend with during the scientific mission?

J.-P. G.: The first difficulty was accessing the study site, given that Palu airport had been affected by the earthquake. The roads of the city and its electrical, and water networks had been severely damaged by the tsunami, the collapse of many buildings onto roadways, as well as by soil liquefaction. The mission’s offshore survey, whose objective was to identify changes in sea floor topography following the earthquake, also proved more complicated than expected, as the waves generated by the tsunami destroyed all of Palu's port infrastructure and ships. Each morning, we had to drive 40 km up the coast to board a ship in a small port less affected by the tsunami.

What initial information has been provided by the samples you took at the site of the catastrophe?

J.-P. G.: We collected sediments deposited by the tsunami (rubble, marine-originated sediments...) along the entire rim of Palu bay. They shed light on the power of the tsunami, its height, and its progression inland. These deposits enabled us to determine that the wave reached a maximum height of 11 m in certain parts of the bay, where it penetrated 400 m inland. Colleagues from the Earth Observatory of Singapore have retrieved deeper samples one meter in depth, in order to inspect the record left by three earlier tsunamis that struck Palu during the 20th century, which are reported by oral transmission. The power of these past events can be appraised by comparing the characteristics of the coarse sediments that they left on land to those generated by last September’s tsunami.

Despite the difficult circumstances, you were able to establish an accurate underwater chart of the bay of Palu. What was the objective of this undertaking?

J.-P. G.: We wanted to understand why a first wave reached the city less than three minutes after the earthquake. Our bathymetric profiles show that this powerful earthquake, measuring 7.5 in magnitude on the Richter scale, destabilized underwater slopes near Palu, causing landslides that may have generated some of the several successive tsunami waves that hit the coastline. They also confirm that the strength of the tsunami was strongly affected by the shape of the underwater slope over which the wave hurtled: in a trampoline effect, the gentler an underwater slope, the more powerful the tsunami, and conversely, the steeper the slope, the more the dynamics of the tsunami are broken. In Palu we are on a delta, and the slope is not steep. The wave had a field day, so to speak, and gathered force.

Are new scientific investigations already being planned?

J.-P. G.: Yes, of course. As part of an upcoming study, we will take deeper samples as far down as 5 to 10 meters below the ground surface. Studying these deep sedimentary deposits will enable us to retrace the chronology of past tsunamis much farther back in time, likely a few thousands of years. With the help of mathematical models, we can generate a relatively reliable estimate of the number of tsunamis that are likely to be produced in the area over the next century.

- 1. Université de Grenoble-Alpes.

- 2. Jean-Philippe Goiran is a geoarcheologist at the Laboratoire Archéorient (CNRS/Maison de l’Orient et de la Méditerranée Jean Pouilloux/Université Lumière Lyon-2).

- 3. This international mission, overseen by scientists from the Tsunami and Disaster Mitigation Research Center, Palu University, and the Jakarta-based Ristek, brought together twenty scientists from Indonesia, Singapore, Great Britain, France and Australia. The French team's research was financed by the scientific service of the French embassy of Jakarta, PHC Nusantara, LabEx IMU and CNRS.

Explore more

Author

After first studying biology, Grégory Fléchet graduated with a master of science journalism. His areas of interest include ecology, the environment and health. From Saint-Etienne, he moved to Paris in 2007, where he now works as a freelance journalist.