You are here

Of volcanoes, scientists and politicians

Mayotte, January 2019. Wide-eyed shoppers in the local markets were amazed to find fish of the Macrouridae (grenadier) family, even though these are not part of the island’s traditional diet. With good reason, since they live in deep waters, well beyond the reach of local fishermen. An autopsy carried out by a vet on a specimen found dead 35 kilometres off the coast showed that “the lesions identified were caused by gas supersaturation, like those encountered in decompression sickness… In fact, the fish does not appear to have died from intoxication…but rather because it was fleeing danger…”.

Birth of France’s fourth active volcano

This episode was in fact only the most recent in a series that had begun eight months earlier, more precisely on Tuesday, 15 May, 2018 at 6:48pm local time, when the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in the Comoros struck. With a magnitude of 5.8, it was widely felt throughout the island of Mayotte and in other islands in the archipelago, causing a wave of panic and raising well-founded questions, as well as fuelling every theory imaginable, including that of an oil exploration campaign, a sea monster, and the spasms of a zebu buried alive.

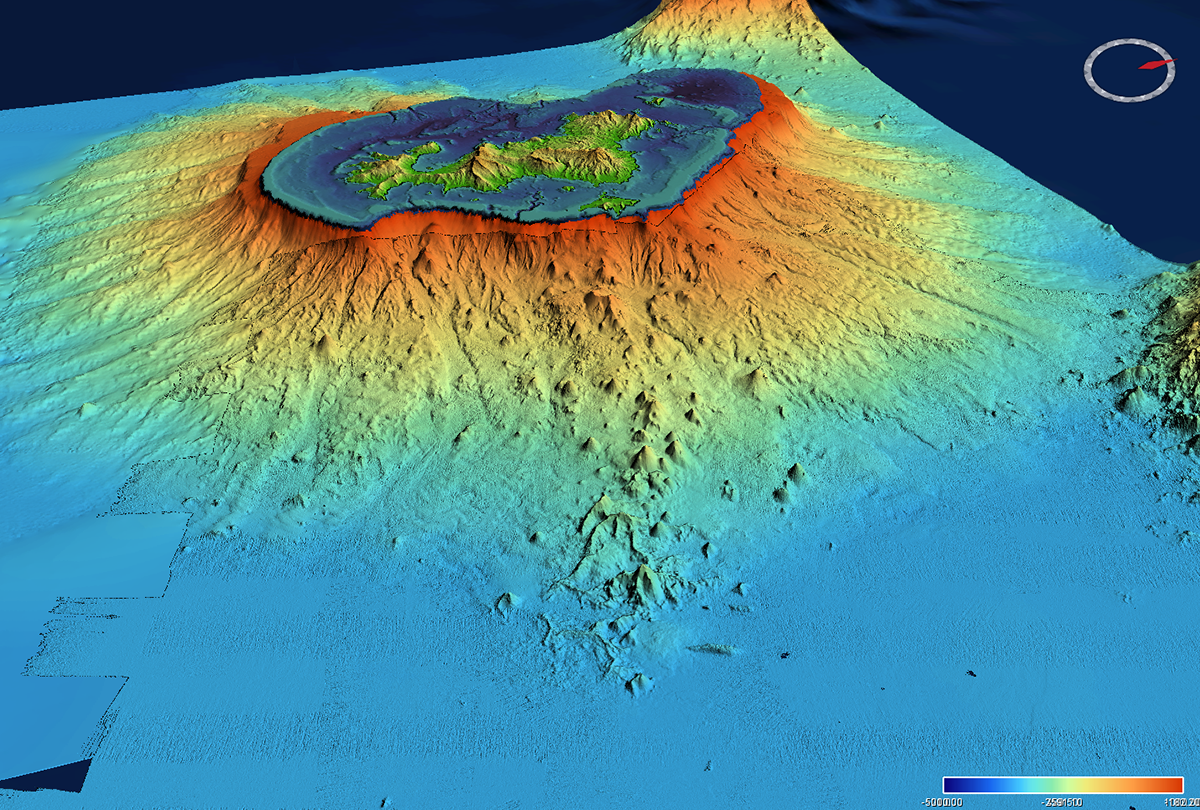

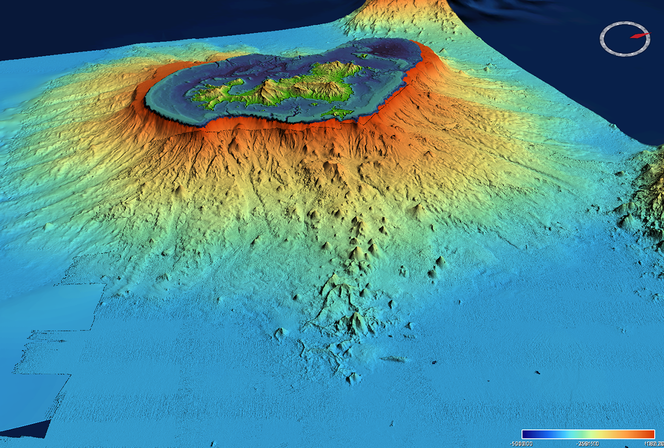

However, the quake also marked the beginning of a dramatic scientific investigation that would last several months. Oceanographic research vessels bristling with electronic equipment and computers set out to comb the sea floor more than 3,500 metres down, searching for the slightest anomaly. New seismological and geodetic stations were set up both on land and at sea to bolster the region’s inadequate network. And in May 2019, the culprit was finally discovered: a new submarine volcano 5 kilometres in diameter and 800 metres in height, located some 50 kilometres east of Mayotte, was forming before our very eyes.

Some quakes were detected beneath the island, where significant degassing was observed. It was suspected that parts of the eastern flank of Mayotte might be destabilised, and there was even fear of a tsunami. Researchers swung into action. Even though it is in theory not their role to monitor volcanoes, investigation and monitoring are intimately linked in such situations. While acting for the general good of society, scientists at the same time collect geophysical, geochemical and geological data that inform research and might one day enable them, for instance, to predict a volcanic eruption. In the meantime, it is essential to act quickly, very quickly, in order to process, analyse and make available masses of data, while securing the funding required to keep on working.

When scientists have to deal with politicians

In this case, acting quickly was easier said than done. In the field of telluric hazards,1 potential players are spread across thirteen research organisations attached to eight different ministerial supervisory bodies, and we therefore set off with a serious handicap! In diplomatic terms, this is referred to as the “dispersion of the telluric hazard chain”. There was no other alternative than to appeal to the French Earth Sciences community. This was done at the end of spring 2019, and as a result, 25 specialists from six universities, the CNRS, the IPGP (Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris), the French National Institute for Ocean Science (IFREMER) and the French Geological Survey (BRGM) volunteered to help monitor France’s fourth active volcano.

The French inter-ministerial delegation for major hazards overseas, the DIRMOM, and the Mayotte local authorities were in charge of informing the general public about our discoveries. Here again, this wasn’t self-evident for the researchers, who are used to communicating their findings freely. However, the social and political context in Mayotte is tense, and there was fear that revealing such news might cause the situation to deteriorate further. Indeed, when he found out about the volcano, the then Prefect exclaimed: “That’s all we need!”. This was followed by a string of meetings involving top-level national and local political figures.

At the request of the Prime Minister’s office, the Mayotte volcano and seismic monitoring network, REVOSIMA, was set up in autumn 2019 with two complementary objectives. Firstly, it was responsible for monitoring changes in seismicity and deformation on the island through the collection of data continuously on land and periodically at sea. These elements provided the public authorities with the key information they needed to manage the situation. For example, scenarios for seismic damage and the impact of potential tsunamis, as well as devices for rapid loss estimates in the event of an earthquake, were developed and made available to local stakeholders. And secondly, the REVOSIMA network enabled scientists to continue their work through the deployment of sensors and processing of marine and terrestrial data, together with the analysis and modelling required to have a better grasp of the phenomena at play. The Covid-19 pandemic has given new relevance to Science as a Vocation and Politics as a Vocation, two texts published in 1919 in which the German sociologist Max Weber defines the work of the scientist and that of the politician. In his foreword to the French edition published in 1959, the French philosopher, sociologist and political scientist Raymond Aron summarised the difference between the two as follows: “The vocation of science is unconditionally the truth. Politicians, on the other hand, cannot always afford to speak it.” Scientists have no time for approximations; they want precision and certainties, whereas it must be admitted that, whether dealing with viruses or volcanoes, political leaders need to act urgently and decide amid uncertainty. For want of a hybrid alternative, let’s be pragmatic and keep in mind the dialogue between the blind man and the lame in the eponymous fable by the eighteenth-century French poet and playwright Jean-Pierre Claris de Florian: “I have my ills, and you have yours. Let us unite them, my brother, for thus they will be less dreadful.”

The points of view, opinions and analyses published in this article are the sole responsibility of the author. In no way do they reflect the position of the CNRS.

- 1. Earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions and landslides.