You are here

Europe’s Rising Stars

For the third consecutive year, 12 French-led European projects (for the 12 stars of the European flag) were recognized by the country’s Ministry of Research and Education. The Stars of Europe competition1 rewards successful European projects initiated in France by a private or public coordinating body and completed during the year of the competition (between July 2014-July 2015 for this edition).

The world's largest research and innovation funding scheme

Initiated in 2013 by the then minister of Higher Education and Research Geneviève Fioraso (2012-2014), this event was meant to bolster France’s involvement in the Europe of research, encouraging more French teams to answer European calls for proposals in light of the country’s financial commitment to the EU’s overall research budget. The second edition of this competition also marked the start of Horizon2020,2 the ongoing Europe-wide 7-year funding project, which simplified application procedures and widened the scope of research (organized under three pillars: industrial leadership, excellent science, and societal challenges). Horizon2020 can fund up to 100% of a project’s cost, has a total budget of €80 billion, which makes it the largest funding scheme of its type in the world.

On track for the future

The 14-strong jury (from the public and private sectors) of the Stars of Europe competition based their selection on scientific excellence and output, job creation and financial repercussions (whether direct or indirect), gender equality and youth training, as well as the interdisciplinary nature of the project and its international and societal implications.

This year, out of 163 eligible projects, there were 71 applications (compared with 60 in 2014). Winning categories were the environment (3 projects), information technology, nanomaterials, infrastructures, health (3 projects), science and society, space, and energy—which earned private automaker Renault a commendation for its research on the advanced manufacturing of Lithium-ion batteries. Of the 12 winners,3 three were led by CNRS researchers: AtMol, ACCESS, and CoSADIE.

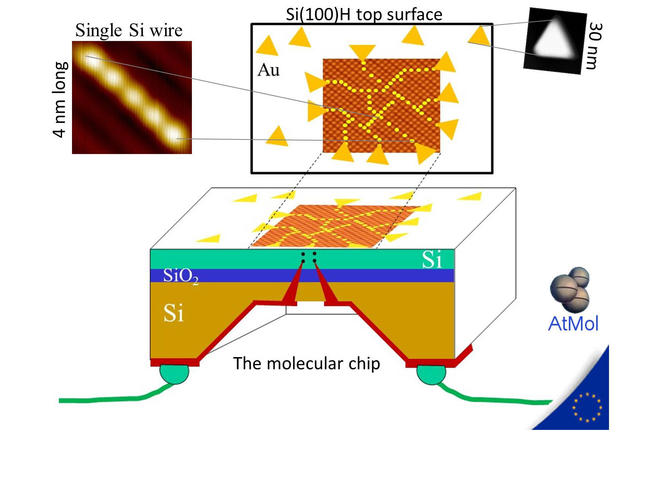

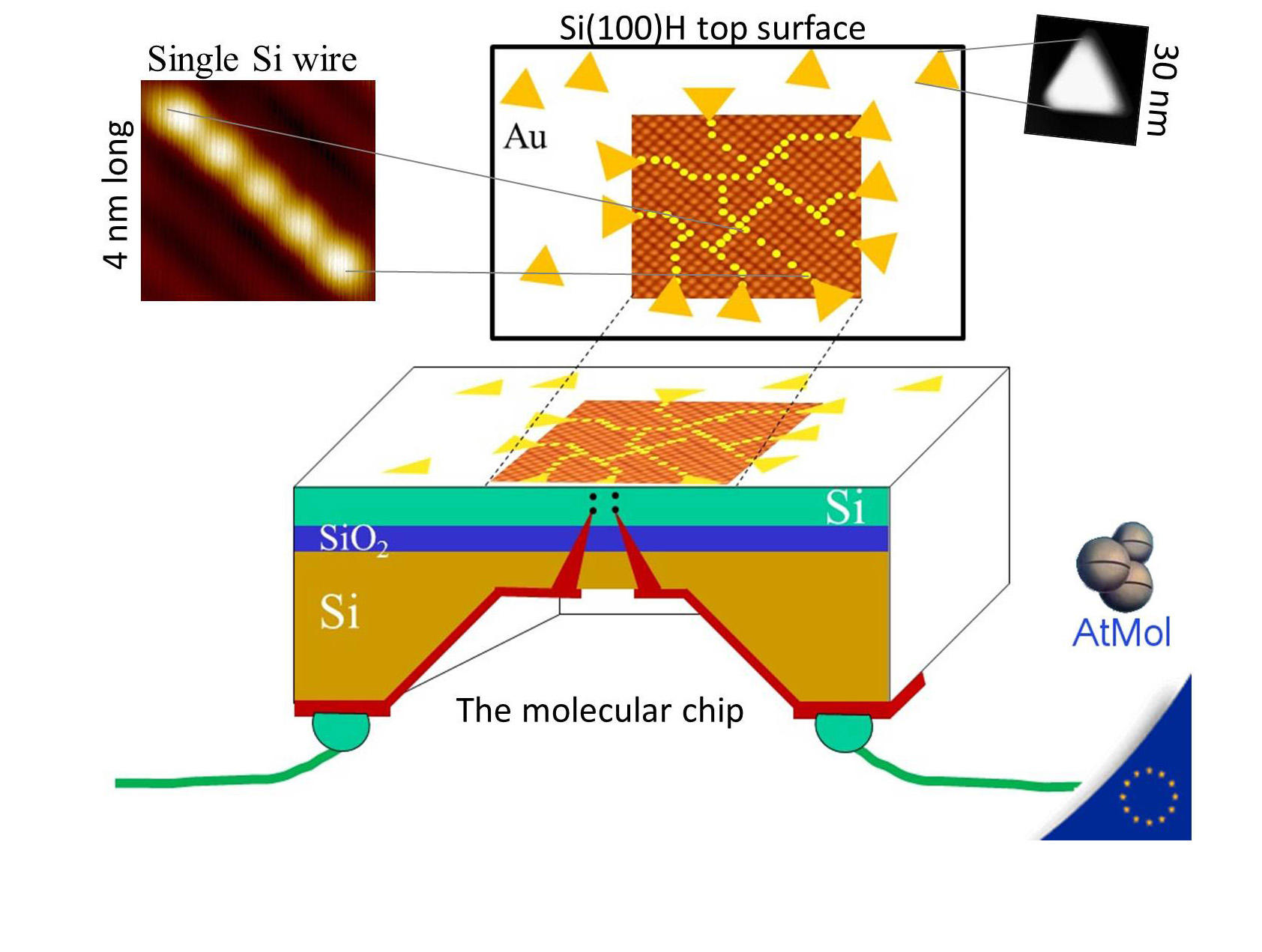

AtMol: building a discipline, one atom at a time

“It really is the culmination of 15 years of European Research,” says Christian Joachim, senior researcher and nanoscience specialist at the CEMES4 in Toulouse. AtMol,5 which was funded between 2011 and 2014 to the tune of €7M, builds up on two past European projects: BUN6 and Pico-Inside.7 “In each case, the objective was to find out scientifically—and in the case of AtMol, technologically—how we could build a processor where the elementary calculation components would be made of a single molecule or a few atoms,” enthuses Joachim. Thousands of these molecular-sized processors could be layered on microchips, which would not only bypass current industrial limits, but also deliver record computational power and low energy consumption. Yet the project was no mean feat: it included 11 international partners, including Singapore’s A*STAR’s Institute of Materials Research and Engineering (IMRE) as the only non-EU participant.

The challenge was to create circuits made up of molecular or atomic wires built one atom at a time. To achieve this, the researchers used on-surface chemistry, single atom manipulations and UHV transfer printing technology. “Our research prompted a manufacturer—ScientaOmicron—to design a new scientific instrument made up of 4 mininiature and very stable scanning tunneling microscopes able to work simultaneously on the same surface with a navigation system based on a scanning electron microscope. It is now sold across the world, which is an amazing result for an application resulting from a scientific process.” Other European projects are now building on these findings and technology to move ahead. “AtMol demonstrated that a single molecule or a few atoms placed one by one on a flat surface could be used to create a minute electronic logic gate. AtMol developed a unique process that goes all the way from producing the wafer in a wafer-fab to the laboratory that can make the atomic circuits.” This project gave rise to more than 104 publications, and led scientific publisher Springer to launch a new series of books to bolster this new discipline. The next projects, PAMS8 and SiAM9—which had already been accepted—will look at scaling and potential industrialization.

ACCESS: The impact of an ice-free Arctic

The Arctic is undergoing some of the most dramatic and visible changes resulting from climate change. Although long-term (covering several decades) and short-term (yearly) forecasts can be made, the complex relationship between sea ice, the ocean and the atmosphere make medium-term predictions difficult. Current models predict that summer sea ice in the Arctic will disappear completely within 20-30 years. How will this impact the region’s marine ecosystems and human activity? This is what the ACCESS10 project set out to understand. Funded between 2011 and 2015 to the tune of €11 million, ACCESS was coordinated by Arctic ocean specialist and CNRS senior researcher Jean-Claude Gascard through the UPMC.11 Some 28 institutions took part in this highly multidisciplinary project, which was split into 5 working groups dedicated to: modeling the Arctic climate; studying how transportation activities (NE and NW passages)would impact the marine ecosystem and local populations; looking at the incidence of climate change on fisheries; examining the risks linked to offshore oil extraction in the Arctic; and focusing on the overall governance of the area.

CoSADIE: Open skies for Europe and the world

Ground and space-based telescopes accumulate Petabytes of data for scientists to analyze, and the rate is increasing. Combining that data and making it freely available to researchers or amateur astronomers across the world in an easily accessible and standardized way is the objective of the Virtual Observatory (VO). CoSADIE,12 which ran from 2012 to 2015, was the latest in a long line of projects aimed at developing a sustainable version of this scheme in Europe—the European Virtual Observatory (Euro-VO). “CoSADIEwas a small project in terms of budget—€475,000 and had one main objective: to coordinate European involvement and ensure Europe’s representation in the international astronomical Virtual Observatory (VO),” explains coordinator and CNRS senior researcher Françoise Genova.13 Over the years in Europe, several programs14 were undertaken to that effect. “Giving access to the open, highly diverse, highly distributed data holdings of astronomy is a challenge, and it has to be sustainable in the medium and long term. CoSADIE performed a detailed study of all the elements necessary to optimize and continue to operate the Euro-VO. We looked at both technical specificities, but also personnel training, and the national initiatives already in place with our partner institutions in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK,” the researcher adds. CoSADIE’s findings and the next phase of the European Virtual Observatory now rest with the H2020 open science project ASTERICS,15 in which the CNRS plays a key role. Benefiting from a €15 million funding, it focuses notably on how to make astronomy-based big data accessible to researchers and the general public. It will include data from large infrastructures like the Square Kilometer Array SKA or the ESO's European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT).

“A fantastic human adventure”

A clear objective and flawless communication are essential for future coordinators who wish to answer European calls for proposals. “You need real collaboration between the partners—each party must have a clearly-defined role to play,” says Genova. For AtMol’s Joachim, who has led three European projects, “if you start a project to get funding, you’ve already lost. The first thing is to focus on the problem, and see how it can be solved. Only then do you make a list of tentative partners, find the specialists you need, and see whether the allocated funding is enough,” he says. “It’s a fantastic human adventure, as it entails meeting the partners, talking to them, motivating them, which can be very important when dealing with projects over the long term.” Needless to say, the Europe of research is well underway.

- 1. Les étoiles de l’europe. http://www.horizon2020.gouv.fr(link is external)

- 2. https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/(link is external)

- 3. Full list of winners available soon.

- 4. Centre d'élaboration des matériaux et d'études structurales.

- 5. Atomic Scale and single Molecule Logic gate Technologies. http://cordis.europa.eu/project/rcn/97085_fr.html(link is external)

- 6. Bottom-up Nanomachines.

- 7. www.picoinside.org(link is external)

- 8. Planar Atomic and Molecular Scale devices.

- 9. Silicon at the Atomic and Molecular scale.

- 10. Arctic Climate Change Economy and Society http://cordis.europa.eu/project/rcn/98430_en.html(link is external)

- 11. Université Pierre et Marie Curie.

- 12. Collaborative and Sustainable Astronomical Data Infrastructure for Europe http://cordis.europa.eu/project/rcn/104381_fr.html(link is external)

- 13. Observatoire astronomique de Strasbourg.

- 14. Astrophysical Virtual Observatory (AVO, 2001-2004), VOTECH(2005-2009), Euro-VO Data Centre Allliance (EuroVO-DCA, 2006-2008), Euro-VO Astronomical Infrastructure for Data Access (EuroVO-AIDA, 2008-2010), Euro-VO International Cooperation Empowerment (EuroVO-ICE, 2010-2012).

- 15. Astronomy ESFRI and Research Infrastructure Cluster. https://www.asterics2020.eu/(link is external) . The project is led by ASTRON (NL).