You are here

Claire Voisin, 2016 CNRS Gold Medal

On September 21, 2016, the mathematician Claire Voisin was awarded the CNRS Gold Medal. She follows 2015 laureate Eric Karsenti and joins the exclusive list of winners of France’s highest scientific distinction.

A renowned specialist in algebraic geometry, Claire Voisin is recognized by her peers, especially for her research on "the topology of projective varieties of compact Kähler manifolds” and Hodge theory, an important branch of this discipline. The latter was reinvigorated in the 1950s, especially by the French school, notably the work of Jean-Pierre Serre and Alexander Grothendieck, and has seen many recent developments.

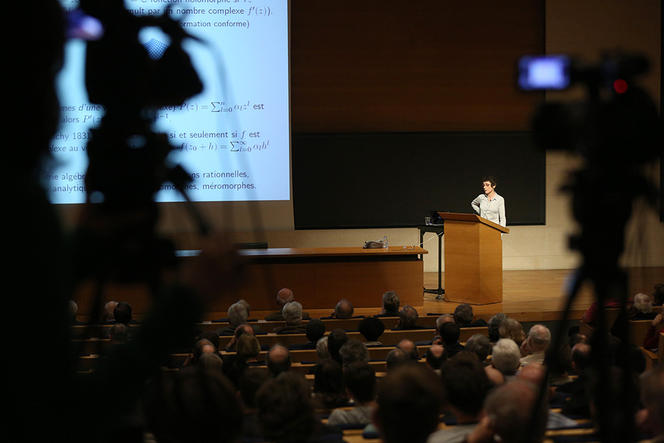

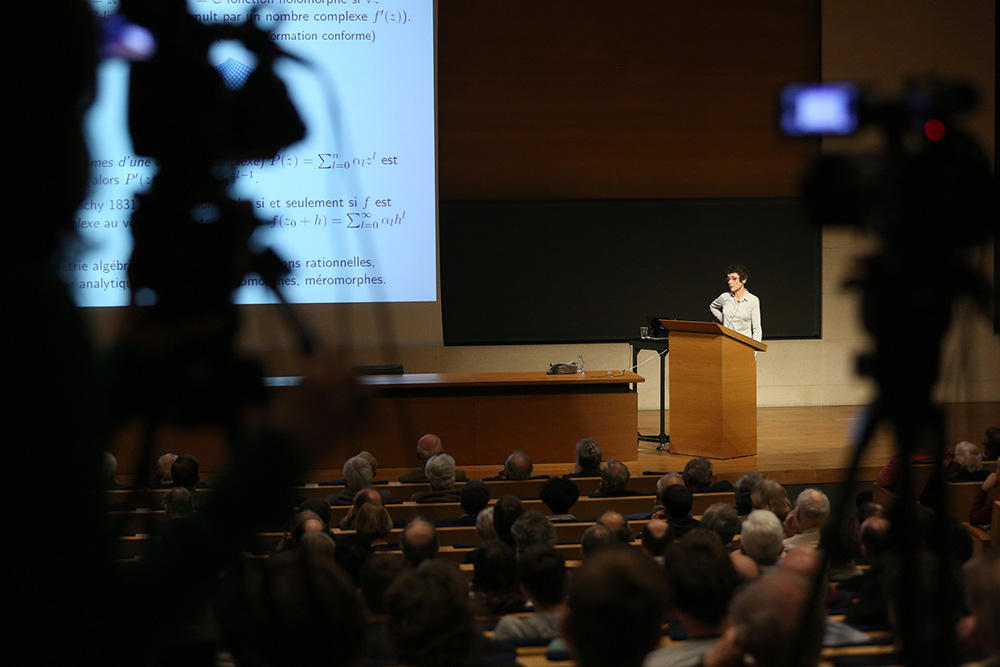

For Claire Voisin, 2016 will also have been marked by her inaugural lecture at the Collège de France on June 2. She was appointed new chair of algebraic geometry after having spent 30 years as a senior researcher at the CNRS, and became the first female mathematician to enter the Collège de France.

Born in 1962, Claire Voisin has received many awards during her career, such as the CNRS Silver Medal in 2006 or the Clay Research award in 2008. Following this accolade, CNRS International Magazine published a profile, which we have republished below. Claire Voisin will officially receive the Gold Medal on December 14, during a ceremony at the Sorbonne in Paris.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

CLAIRE VOISIN, ARTIST OF THE ABSTRACT

By Charline Zeitoun (this profile was published in CNRS International magazine Issue 13—April 2009)

Very quickly, words no longer suffice. Claire Voisin goes to the board, eraser in one hand, chalk in the other, and draws geometrical figures side by side with complicated calculations. Voisin, a senior researcher at the Institut de mathématiques de Jussieu1 in Paris is a specialist in algebraic geometry. More specifically, she works on the study of the “topology of complex algebraic varieties.”

To introduce her field, she sketches a sphere that she cuts up in three-dimensional triangles with curved edges, as if they had been shaped by the rounded surface. The result is that you can cover a sphere with triangles, which are themselves the “faces” of a pyramid, for example. “Topologically speaking,” Voisin explains, “a sphere and the surface of a pyramid are therefore identical—though saying something like that is an absurdity from the point of view of algebraic geometry,” she immediately points out. According to her, “this is also possible with an inner tube that has one or more holes.” If “triangulated,” the result is a skeleton made up of triangles stuck together along their sides. A metric induced by the ambient space then gives rise to a complex structure, hence to a Riemann surface, which turns out to be a purely algebraic object, a projective curve. And in higher dimensions, the problem becomes even more complex. To get from one figure to the other therefore involves a mathematical trick, the precise details of which are very difficult to grasp for a non-specialist, involving such words as homeomorphism, simplex, Riemann surface, transcendental functions, etc. But the general idea is clear: moving between the “topological,” the “algebraic,” and “complex geometry,” the result is a “multiplicity of perspectives of one and the same object” using different mathematical approaches. “What's exciting about my work is this constant moving back and forth several geometries and several types of tools to prove results in one field or another,” Voisin continues.

She resembles the typical mathematician as we often imagine them, with a particular ability for abstract thinking. In fact, though mathematics came easy to Voisin both at school where she was already boning up on final year courses, then at the École normale supérieure and while doing her PhD, she knows that for all intents and purposes, she speaks a language that is foreign to most ordinary people. It's not easy to follow what she says. That's true even for the students studying for their Masters in mathematics, to whom she teaches a few courses a year, attempting to “explain these superb ideas.” Yet they often drop out, discouraged by the complexity of the field. “It's very frustrating not to be able to get across all the things that mean so much to me in my work and research,” says Voisin regretfully. She remembers the six months during which she was an assistant professor, before she got a CNRS position, as being “hellish.” “Joining CNRS saved my life!” she jokes.

Becoming a full time researcher at the age of 24, she could at last devote herself entirely to algebraic geometry, the study of the properties of sets defined by algebraic equation systems, which is at the heart of the most abstract mathematics. “There is creative drive in mathematics, it's all about movement trying to express itself,” Voisin confides. Nothing to do with the “boring, dead, and dry” mathematics taught in secondary school, where the courses go through an endless series of “definitions, properties, and theorems” using a method that is “always under control, as if on tracks,” and which is applied to “simple exercises in logic.”

After her doctoral thesis, she became fascinated by a tool that is well known to topology specialists, Hodge theory, which can also be used to tackle complex algebraic geometry. Published in 2003, her book on the subject has rapidly become a reference. She won a number of prizes and awards, such as the CNRS bronze (1988) and silver (2006) medals, and the Clay Research Award (2008) from the Clay Mathematics Institute,2 for her work on Kodaira's conjecture, another problem in complex algebraic geometry. As an editor of several mathematical journals, she always keeps an eye on the development of her discipline. In her private life, she is also a mother of five, and her eldest daughter started studying mathematics. “But her field is far removed from mine and that of my husband—also a mathematician—so as to avoid any family 'pressure,'” she explains. “In any case,” she adds, “we never talk maths at home!”

Charline Zeitoun, April 2009.