You are here

Arabian Rock Art Thrown into New Relief

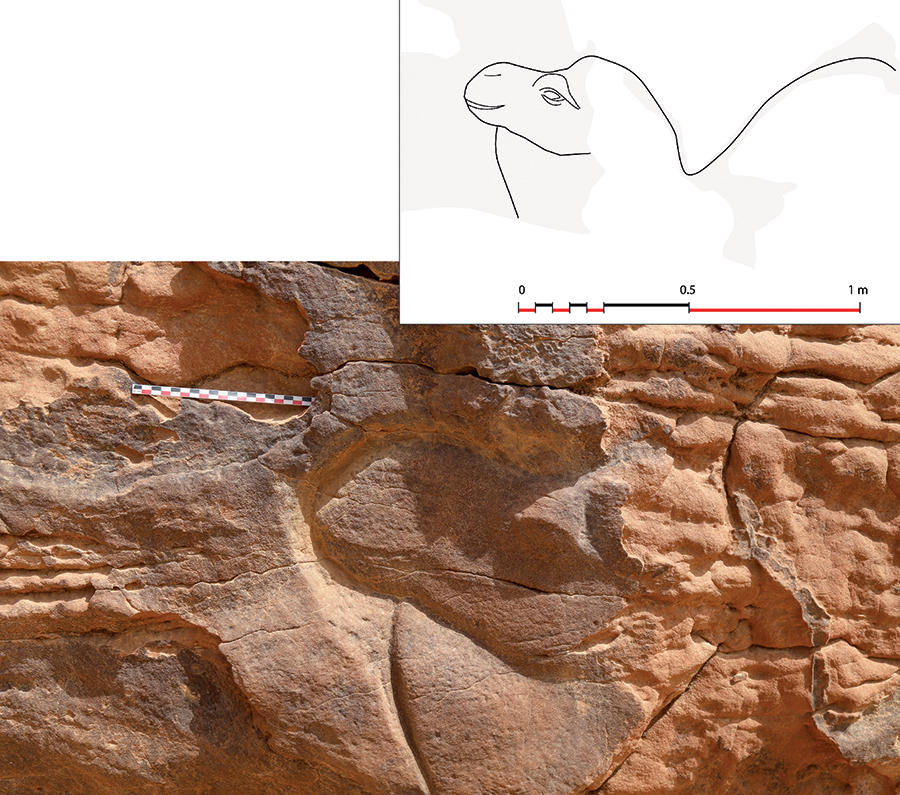

Ancient sculpted bedrock depicting life-sized camelids and equids was recently brought to light in the northern Saudi Arabian province of Al-Jawf. In a region where engraving and—albeit to a lesser extent—painting were far more widespread during antiquity, this rare example of carving could be key to understanding the art of rock relief in Arabia.1

Like many others, this breakthrough owes a lot to chance. Located in an isolated area, enclosed within a private property, the long-forgotten and damaged reliefs would have continued to escape the world's attention, had it not been for the insight of locals and their insistance to show them to a team of French and Saudi2 scientists, who have just published their first results in the journal Antiquity. "These findings, in a sector that remains virtually unexplored, are truly unique," says Guillaume Charloux, of the CNRS Orient & Méditerranée joint research unit,3 who surveyed the site in 2016 and 2017.

Located 8 km north of the city of Sakaka, the three rocky outcrops making up what is now known as "Camel Site" exhibit low and high relief realistic representations of at least eleven dromedaries and two donkeys or mules. Obviously the work of skilled carvers who respected proportions, the twelve naturalistic panels and reliefs depict animals without loads, in active postures and in a natural setting. Diverging from the two-dimensional and schematic official Arab tradition, they could be influenced by the craftsmanship of the then neighboring Nabataean and Parthian populations, as the rocks lie in the vicinity of several Nabataean sites and the carvings bear strong resemblance with the camel caravan featured in the Siq of Petra. They are also reminiscent of Mesopotamian art, especially that of Hatra, an ancient city that now lies in the north of Iraq.

Uncertain dating

Comparison with Parthian and Nabataean models also suggests the sculptures may date back to the first centuries BC/AD, although lack of evidence prevents certainty. However, the patina that covers these works testifies to their antiquity, as does the fact that the blocks bearing them fell from their original position as a result of erosion—a long process over time.

The various themes represented (different species meeting, grazing, a camel caravan) do not indicate a specific date either, although it has been established that dromedaries and donkeys were present in the region from the 5th-4th millennium BC (but domesticated much later), and horses are thought to have been introduced in Arabia in the second half of the first millennium BC.

The absence of tool marks, wiped away by erosion, or of known engraving artefacts such as picks and burins in the surroundings also prevents accurate dating. "Apart from the flint found nearby, we have no diagnostic material, and we are not sure whether these tools were used to carve the sculptures," Charloux says. In addition, the rocks bear no inscriptions, further adding to the enigma.

A site surrounded in mystery

Besides the lack of anthropic clues, other signs of human presence are conspicuously lacking in the desertic landscape around Camel Site. The absence of any water source and the arid climate are not conducive to permanent human occupation, which raises the question of who made the sculptures and why.

Again, the answer is not clear-cut: "the Nabataeans were strongly implanted in the area, and could have had a community nearby. They also traded with Mesopotamia, which suggests the spurs may have been a milestone on an ancient caravan route," Charloux explains. Easy to spot in the barren surroundings, Camel Site could have been the starting point of a desert crossing or the boundary of a political or tribal territory. Or a place of worship, as pointed to by the cup marks resulting from the friction of multiple hands on the rock, possibly to obtain "magical" powder, over the centuries.

While "the site is shrouded in mystery that won't be solved for a long time to come," one thing is certain: the carvers were talented artists—possibly local as suggested by the originality of the themes chosen and techniques employed—who showed surprising mastery and sense of aesthetics. "It took several people to complete these representations and several days for each one," Charloux points out. This is reflected by the variety of styles observed, in particular in the modeling of the animals' heads and legs.

The unconventional nature of Camel Site, whether in "chronological, geographical, technical, thematical and stylistical" terms, makes it quite exceptional, hence the researchers' concern to protect it—an endeavour that has been swiftly undertaken by the Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage—and commitment to draw the international scientific community's attention to it. "We now hope that rock art specialists will take an interest in it," Charloux concludes. And bring Camel Site out of millennia of solitude.

- 1. G. Charloux et al., "The art of rock relief in ancient Arabia: new evidence from the Jawf Province," Antiquity, 2018. 92(361):165-82. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2017.221

- 2. At the Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage.

- 3. CNRS / Sorbonne Paris IV / Panthéon Sorbonne / EPHE / Collège de France.

Explore more

Author

Valerie Herczeg is a CNRS bilingual journalist who also heads the translation department of the CNRS Communications Department.