You are here

Addiction is not hardwired in the brain

The medical concept of addiction originated in the United States in the 18th century. How was it described back then?

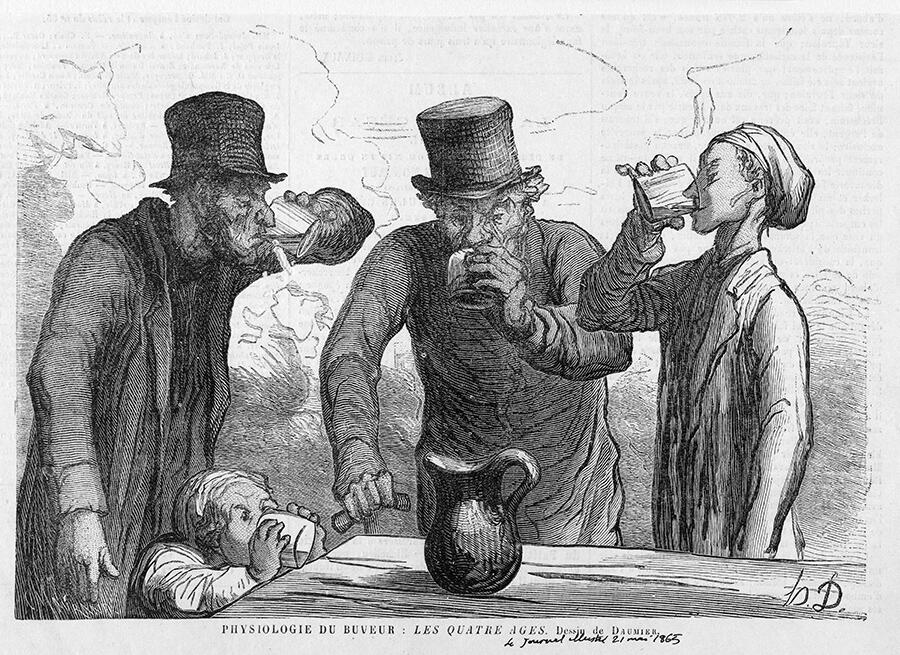

Serge Ahmed1: At the time, the consumption of spirits with high alcohol content (gin, whisky, etc.) was rising and becoming widespread, causing a veritable epidemic of chronic, immoderate use, with all of its attendant problems for the family and society. Observing this evolution, the American physician Benjamin Rush formulated the idea that excessive drinking was in fact a disease, alcoholism, and not a moral issue, as was commonly assumed in those days. He realised how difficult it is for alcoholics to initiate and voluntarily sustain abstinence, especially when it’s accompanied by intense physical and mental symptoms: tremors, sweating, palpitations, anxiety attacks. In fact, in some cases abrupt withdrawal can even lead to death. This idea evolved over time, giving rise in the late 19th century to the concept of addiction-dependence, which held considerable sway until the end of the 1980s. According to this concept, alcohol addiction is an artificially acquired pathological need that can only be relieved by consuming more alcohol.

So addiction was essentially defined in negative terms, as a need, a dependence…

S. A.: Yes, exactly. It was thought that addiction is first and foremost a pathological need, in the sense that it is acquired through the chronic consumption of alcohol, an exogenous substance with little biological utility. When this need is not fulfilled, it results in a craving similar to hunger and thirst. As a result, the person can no longer function normally. This is also referred to as dependency (alcohol dependence).

From this perspective, the continued use of the substance is not motivated by a vice, an insatiable quest for pleasure, but rather by the fear of feeling the need, by a desire to avoid the suffering caused by withdrawal syndrome. In this light, it is easier to understand why consumption can continue to the detriment of nearly everything else: family, job, etc. In the 19th century, this concept was extended to other substances, especially opiates (opium, morphine, codeine) and later opioids (heroin, fentanyl), whose chronic use can also lead to very severe dependence and craving.

How did today’s medical definition of addiction develop?

S. A.: The early 1980s saw a massive increase in the use of cocaine, amphetamines, tobacco, cannabis… Substances that, when the user stops taking them, do not induce a withdrawal syndrome as severe and agonising as with alcohol or opiates. It was also during that period that we began to understand how drugs act on the brain, especially on the recently-discovered reward circuit, whose stimulation can serve as motivation by itself, in the absence of any physiological need. It was also observed that most of the drugs with addictive potential in humans are also consumed by other animals, sometimes avidly, without causing dependence. Researchers then began to wonder whether reliance is really central to the medical definition of addiction.

This line of thought eventually led, in the late 1980s, to the idea that addiction is above all a behavioural dysfunction or disorder, characterised by excessive consumption associated with a craving and a diminished capacity for control. Withdrawal and dependence would soon be relegated to the background, with loss of control, craving and compulsion becoming the key elements in the definition of addiction. This conceptual reconfiguration also led to a considerable broadening of the scope of application of the concept, from drugs to non-substance behaviour like pathological gambling. From there, one of the major challenges for neuroscience research was to define the mechanisms and cerebral dysfunctions responsible for this loss of control and regulation capacity. Today, despite significant progress in the field, we are still looking for the answers.

When did non-substance addictions start to be recognised?

S. A.: Incidentally, we recently rediscovered an almost forgotten manuscript dating from the 16th century that describes pathological gambling in very modern-sounding terms! The author, a Flemish doctor named Pascasius Justus Turq, was himself a compulsive gambler and therefore quite familiar with the problems caused by betting games, which were already very popular at the time. But his work had no direct impact on the subsequent evolution of the concept of addiction. It wasn't until the late 2010s that the World Health Organization officially recognised gambling and video games as non-substance addictions.

Pascasius may well be rejoycing in his grave! Research is continuing in this field, and in the medium or longer term this recognition can be expected to extend to other non-substance addictions, for example to social networks, porn sites, hyperpalatable foods (high in added sugar), etc.

Given this expansion of the scope of addiction, should the definition of what constitutes a ‘drug’ be revised?

S. A.: No, I don't think so. These evolutions mostly change the classification of objects and activities with addictogenic potential, in other words that are likely to lead to addiction in some people. For example, for every 100 users of cocaine, the percentage that become hooked is estimated at 15%. The figure is about 30% for tobacco and 10% for alcohol and cannabis. The estimates are less well established for pathological gambling, but it should be around 5%, which is similar to hyperpalatable foods. Previously, all drugs were thought to be addictive to varying degrees due to their direct action on the brain’s reward circuitry. Today we know that any behaviour that can quickly activate this circuit, even indirectly, can induce dependence.

Since the invention of cigarettes, slot machines, online gambling, ultra-processed foods and porn websites, manufacturers have continued to show ever-greater ingenuity, using the most innovative technologies to create and develop new addictogenic products, objects and activities. Some historians and sociologists even go so far as to say that since the late 20th century our societies have entered the era of addiction.

If substance and non-substance addiction obey the same basic principles, will their treatments be the same?

S. A.: In broad strokes, the behavioural and psychological treatments for the different types of dependence will be quite similar in that they target the underlying mechanisms and processes common to all addictions. To cite just one example, some approaches rely on deconditioning the stimuli that trigger the desire to consume, learning how to resist them or mitigating their importance. These interventions can be applied to all addictions. The same is true for approaches based on self-help and support groups.

On the other hand, drug therapies can be more specific to a given addiction, because each substance has its own pharmacology. For example, the use of disulfiram targets alcohol reliance, and methadone, heroin addiction. However, recent research indicates that certain psychedelic compounds, like psilocybin or ketamine, despite their highly-targeted pharmacologies, could have beneficial effects in the treatment of many compulsions (alcohol, tobacco, cocaine). The reason for this broad spectrum of action has yet to be determined.

And yet, the medical concept of addiction does not seem to be unanimously accepted by scientists. Why is this?

S. A.: What is being questioned, or even challenged by some, is mainly the hypothesis that addiction is a chronic brain disease. Indeed, this conjecture is often dogmatically presented as an established fact, in particular by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) in the United States, which wields a dominant influence in the field, including in France. But despite numerous scientific breakthroughs, it’s still not possible to determine whether or not an individual suffers from an addiction simply by examining their brain.

Furthermore, many addicts manage to recover, to overcome their dependence, with no medical or professional help, which is not really compatible with the idea that these people suffer from a chronic, recurrent brain disease. This is referred to as ‘spontaneous’ remission, since the factors at work are not yet fully understood, even though recovery is suspected to be largely dependent on individual decisions and a more or less favourable environmental context. Unfortunately, these remission phenomena have been the object of too little research, which will nonetheless be essential for more clearly defining the nature of addiction as a disorder from which recovery is ultimately possible, despite relapses and other difficulties.

What does the medical concept of addiction change in terms of society's perception of addicts?

S. A.: One might think that a chronic brain disease status would be beneficial for those concerned, in particular by reducing the negative psychosocial effects resulting from the stigma and bias that they often endure. Sadly, in practice it’s not that simple. In fact, it has been observed that this status does not protect from discrimination, and sometimes even exacerbates it. In addition, when addicts become convinced that they suffer from a chronic brain disease, it may lead them to stop fighting their addiction – although it is well known that self-motivation plays a key role in recovery. In this sense, imposing a medical hypothesis as an established fact, however plausible it may be, can have counterproductive effects for the individuals in question.

I would therefore recommend that we continue to use the ‘addiction as brain disease’ hypothesis to guide part of our scientific research on dependence, while being careful not to brandish this postulate as an established scientific truth, so as to avoid negative consequences for those we are trying to help. ♦

For further reading on our website:

Illicit drugs: In the name of the law

- 1. Serge Ahmed is a CNRS research professor at the INCIA (CNRS / Université de Bordeaux).

Explore more

Author

Léa Galanopoulo has a biology degree and is currently studying scientific journalism at Paris-Diderot university.