You are here

The memory of 13 November gradually comes to light

On the night of 13 November 2015, terrorist attacks took place near the Stade de France, in outdoor cafés in the east of Paris, and in the Bataclan concert hall, resulting in 130 deaths and more than 350 wounded. A few days later, two researchers, Denis Peschanski1 and the neuropsychologist Francis Eustache,2 launched a vast research programme focusing on the memory of this tragedy. The objective of this long-term interdisciplinary project, with contributions from a dozen laboratories, is to understand how the memory of an event is constructed and how it evolves – both at the individual and collective level – by gathering witness accounts at regular intervals.

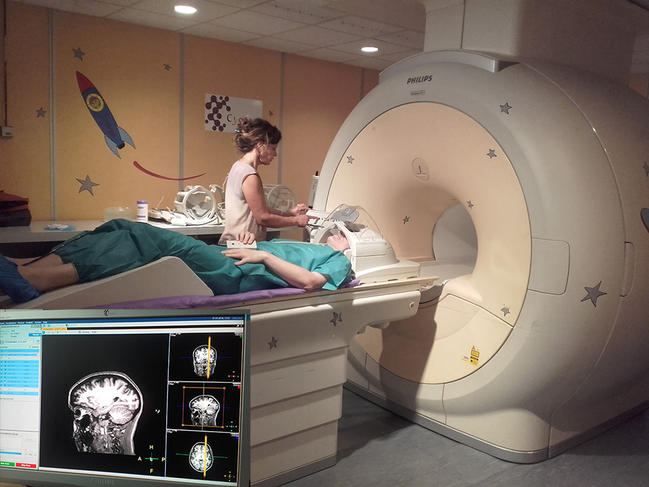

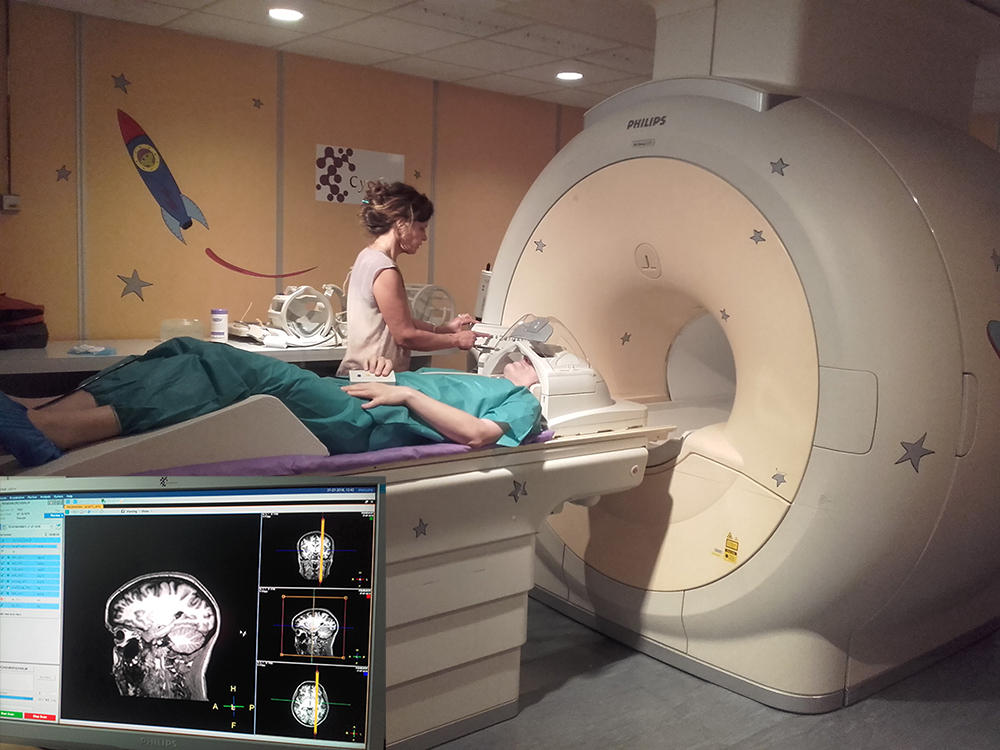

"The study focuses on a cohort of 1,000 people who directly or indirectly witnessed the 13 November attacks in Paris," explains Denis Peschanski. "It includes multiple waves of interviews conducted a few months after the tragedy, and then two, five, and ten years afterwards. It is accompanied by a biomedical component, known as Remember, based on brain imagery." The purpose of this second component, which follows 120 direct victims of the attacks and a control group of 75 volunteers, is to shed light on how Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) arises and works, in other words why certain witnesses continue to be haunted by the vivid memory of the tragedy, while others are more resilient. "We've known for a few years now that the memories that we all build are not fixed once and for all,” adds Francis Eustache. “They are subject, throughout one's lifetime, to a subtle consolidation and reconsolidation process. The same is true of collective memory, which continues to evolve over time."

Two waves of interviews have been conducted to date, in 2016 and 2018, along with two series of biomedical studies. The diligence of the participating volunteers came as a surprise to the researchers. "The psychiatrists we had informed about the project warned us that the individuals most directly affected by the attacks, in other words victims or their relatives, could potentially find it difficult to speak and abandon the project," Peschanski recounts. "But it was just the opposite. Not only did witnesses from the 'first circle' respond in large numbers to our call, representing nearly 40% of the cohort, but they were also the ones who spoke the longest: 2.5 hours during the final series of interviews, as opposed to an average of 1.5 hours for the group as a whole."

The sum of recorded accounts was also impressive, totalling 1,430 hours for 2016 alone. "The transcription of testimonies ended this year. To start with, it enabled us to construct a history-narrative of 13 November, recounted by and in the actual words of direct witnesses." This polyphonic narrative, published in early November by Odile Jacob,3 is based on 360 testimonies (170 of which are featured in the book) of close witnesses – victims, their loved ones, and the firefighters and police officers who intervened at the site of the attacks. "The challenge here is the transition from the truth of the witness to that of the event, by crossing oral sources very close to the attacks," Peschanski adds. Other studies should follow: a textometric analysis has already been scheduled to compare the lexical field used by witnesses of the tragedy, depending on their proximity or distance from the attack. Long-term qualitative analyses of thousands of hours of recording should be performed at a later stage, as should comparison of the testimonies gathered in successive waves.

The CREDOC (Centre de Recherche pour l’Étude et l’Observation des Conditions de Vie), a partner in the 13 November project, has already delivered some of the initial findings from its study of the collective memory of the event, and how it changes over time. During each wave of interviews, a representative sample of 2,000 individuals are asked a dozen questions about the attacks that have occurred since the early 2000s. "The evolution of answers between 2016 and 2018 has already confirmed some of our hypotheses. It reveals in particular that 'flash bulb memory', or the memory of the circumstances surrounding a particularly striking personal or collective event – where we were, who we were with, etc. – remains vivid for 80% of respondents, and shows practically no variation from one wave to another."

By contrast, over the same period, the memory of the events themselves becomes less precise, and tends to be more condensed. For example, the 2015 attacks – which included those on Charlie Hebdo and the Hypercacher supermarket in January – are exclusively referred to as “13 November” attacks. And their different locations – the Stade de France, the outdoor cafés in the eastern districts, and the Bataclan – gradually disappear in favour of a single reference to the Bataclan, and even to Paris. "These results are related to the phenomenon of memory condensation," Peschanski explains. "They confirm the connection between remembering and forgetting, as the former is not possible without the latter."

Forgetting, or at least keeping the most traumatic memories at bay, is precisely the subject of the Remember study, which in February 2020 led to a first, noteworthy publication in the journal Science.4 "It is important to understand that when we form the memory of an event, it is not fixed straight away. Instead, it changes every time we recall it, losing its evocative power until it becomes a sort of awareness in our personal history," explains the cognitive neuroscience researcher and study's main author Pierre Gagnepain.5 “Each new context in which the memory comes up overwrites the previous one, thereby gradually losing strength." The problem is that such attenuation phenomenon does not take place in cases of PTSD – on the contrary, invasive memories are experienced by the sufferer as though they were going through the event over and over again. "PTSD victims relive certain fragments of the traumatic scene, but with an extreme sense of fear and danger."

Until now, the prevailing hypothesis for explaining these disorders was based on dysfunctional memory updating. "Our study shows that it’s not just to do with the functioning of memory itself, but also with how our mind actively erases memories. Control over the relevant parts of the brain, which enables forgetting, is defective." When a memory intrudes among resilient individuals, the areas of the brain associated with control, which are located in the prefrontal cortex, connect to those associated with memory – especially the hippocampus – in order to interrupt their activity and eliminate the thought. In PTSD sufferers, the brain regions related to control activate in the same way, but their message does not make it to those linked with memory." What remains to be elucidated is the root of this connectivity problem: is it due to the propagation of the control signal from the cortex to the zones associated with memory, or to the way this signal is received? A study of the GABA neurotransmitters in the hippocampus should be initiated shortly, in an effort to explore this latter hypothesis, again as part of the Remember project.

Other areas of research should also complement the current initiatives of Remember. "We are about to begin a study on the victims' children, and on how the memory of the attacks is transmitted," Eustache says. "We will investigate how families function, as well as more biological aspects, such as potential traces in the brains of children." The researcher hopes that the exceptional diligence of participants in the study will continue unabated. "Of the 200 participants in 2016, 91% returned in 2018," Eustache points out, stressing the "special relationship" that researchers and attack victims have formed over the years – "a friendly relationship through the prism of science."

- 1. CNRS senior researcher at the CESSP (Centre Européen de Sociologie et de Science Politique – CNRS / Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne / EHESS).

- 2. Director of studies at the EPHE (École Pratique des Hautes Études) and head of the Neuropsychology and Imaging of Human Memory Laboratory (NIMH – Inserm / EPHE / Université de Caen-Normandie).

- 3. "13 Novembre. Des témoignages, un récit", published by Odile Jacob. All of the book's proceeds will go to the 13 November programme.

- 4. "Resilience after trauma: the role of memory suppression."

- 5. Neuropsychology and Imaging of Human Memory (NIMH) laboratory.