You are here

A new currency to dethrone the dollar?

It all started in 1944. The Bretton Woods (United States) Agreement established a new organisation for the international monetary system, making it possible to decorrelate the value of state-issued money from supply and demand. The agreement used a fixed exchange rate to connect all currencies to the dollar, which became the only one convertible into gold. Yet while this system was relinquished in 1971, the greenback remained the reference.

Today a growing number of transactions are conducted in currencies other than the dollar, such as the yuan, issued by China. This can be explained by the growth of the Chinese economy, as well as current-day geopolitical crises (the consequences of the war in Ukraine, namely the boycott of Russia and the abandonment of payments in euros for Russian energy, have led to the European money’s decline among international currencies, in favour of the yuan). China has already agreed to conduct financial and trade transactions directly in Brazilian real or yuan, thereby de facto avoiding conversion into dollars.

Aware of a turning point, and ever on the lookout to free themselves from the dollar, BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) have even envisioned creating their own currency. What form could it take?

A fostered emergence?

For Carl Grekou, an economist at the CEPII centre for research and expertise on the world economy and an associate researcher at the EconomiX Laboratory1, two scenarios are possible: “A first one including a fixed exchange rate between the various monetary authorities of these countries. And a second one, more likely, in which these economies would establish central parity over the medium-term, and conversion rates for each country’s money in relation to this BRICS currency. It is a more flexible system because it allows different countries to adjust as needed, doing so fairly gently compared to devaluations. Central parity would thus play the role of a virtual value for the BRICS money, in relation to which each currency would have an exchange rate. This is the same system as the ECU , the ancestor of the euro.”

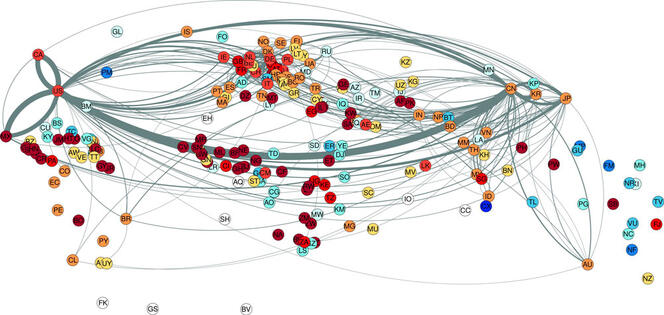

It is therefore worth wondering – while exclusively considering the mathematical structure and volume of trade, and without taking finer economic or geopolitical aspects into account – whether today’s global financial network could foster the emergence of a common BRICS currency. The physicists2 Célestin Coquidé, José Lages, and Dima Shepelyansky recently published a study3 seeking to answer this question by analysing the structure of international trade between 2010 and 20204. “The data studied includes approximately 3,000 products in total (gas, oil, chemicals, machine tools, foodstuffs, manufactured goods, etc.).5 Services were not included. The exchanges observed between two countries over a year amount to the sum of all products exchanged between them, and this translates into a relative export volume, expressed here in US dollars,” explains Coquidé.

For example, country A exports goods with a total value of $100 (US). “To be exempted from conversion between currencies, and especially to take into consideration the trade interaction between the countries, we convert such export into a relative export volume. In other words, in the network of international trade in which competition between currencies is simulated, export ties are expressed as a percentage of total exports. In this example, we would have a relative volume of 10% if the exports of A to B represent 10% of A’s total exports. As a result, when a currency is attributed to a country in our simulations, the volumes of exchange always remain devoid of a currency.”

Global trade as an influence network

To develop their mathematical model, the researchers used a “spin model”, which is employed in physics to describe certain quantum states of matter in the presence of magnetic fields. “But it is also used to replicate sociological behaviour, notably to track changes in voting within a particular population, namely by considering that each person is influenced by those they interact with,” explains Lages. This model enabled the researchers to assess the effect of the three major economic hubs embodied by three currencies: the US dollar, the euro, and a new BRICS currency.

“To understand this model, each currency should be seen as an opinion, and the network of transactions as a network of social interactions. It is then necessary to observe how public opinion evolves in this network, by taking as parameters the direct trade of each country with its economic partners, as well as the size of each of these partners within the global network,” Coquidé explains.

To apply their model, the researchers first defined the countries that would invariably keep the same currency: nine European nations would choose the euro, the United States and a few English-speaking countries the dollar, and BRICS members their “new” money. “For all other states, we randomly attribute a currency from the first phase of simulation. During each subsequent phase, the preferred currency associated with each country and used for its financial transactions changes according to the trade interactions between these countries and their partners. In other terms, the more a partner state is economically significant globally, the more trade with it will be large in terms of the relative volume of imports and exports, and the greater the chance that this partner’s money will be transmitted to the country in question,” Coquidé adds. “A phase ends when we verify whether each nation’s currency remains the same, or whether it should change. The simulation ends when the currencies associated with each state no longer change from the preceding phase. To ensure the statistical reliability of our results, we conduct ten thousand random simulations for each initial set of parameters.”

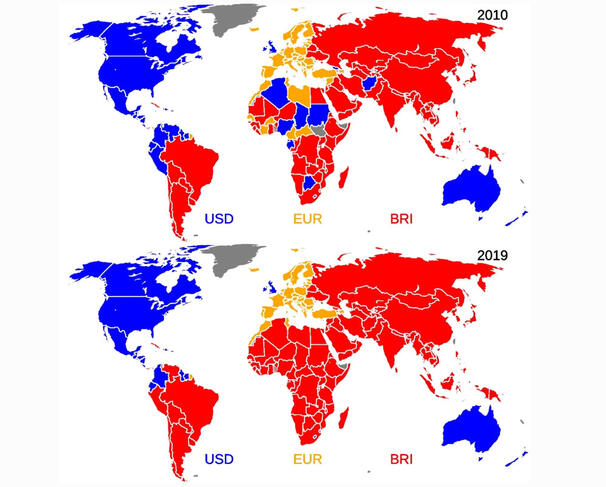

The rise of BRICS during the 2010s

The researchers generated a map of the world divided between the three currencies, at different periods of time during the decade being studied. “In the 2010s, the English-speaking world preferred the dollar, while BRICS countries and some Asian ones would have favoured the BRICS currency. Europe and the Mediterranean basin chose the euro, while Latin America was split between BRICS and the dollar. Africa was divided in three until 2012, when the BRICS money began to win out across the continent,” remarks Lages. “In 2020, only Morocco and Tunisia still opted for the euro.”

Preference for the dollar henceforth included only the largest English-speaking countries, the UK and Australia to start with, followed by Mexico and most of Central America. Those in South America and Asia chose the BRICS. Depending on the results, it would be more advantageous for 60% of the world’s nations to conduct their transactions in the BRICS currency, as opposed to 21% for the euro and 19% for the dollar. This zone of influence covers the vast majority of developing and less economically-advanced countries. These findings enabled researchers to draw a parallel with the famous law stating that “bad money drives out good”6.

Does this map clearly reveal a loss of influence of the euro and the dollar with the potential arrival of a BRICS currency? For Yamina Tadjeddine-Fourneyron, professor of economic sciences at Université de Lorraine, and deputy director of the BETA7, such conclusions seem hasty. The researcher was surprised by the interpretations of the spin model simulations, especially the fact that a large part of Africa would switch to the BRICS currency. “The fact that African countries increased their exports to BRICS during that period does not necessarily mean that the euro had less influence over part of Africa. Countries in the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), with the exception of Nigeria, use the West African CFA Franc, which is by statute fixed to the euro. I am just as startled to see that in this model, Cambodia and Argentina, which use the dollar for their domestic payments, fall under the BRICS currency.”

Trade is not enough to establish a common currency

These elements show the effective limits of this study, the first being that it is difficult to assess the potential attractiveness of a currency that does not exist. “A common currency cannot be established just on the intensity of trade relations. Similar political, economic, and social characteristics must be taken into account in order for it to be viable,” reminds the economist Valérie Mignon, a professor at Université Paris Nanterre, researcher at EconomiX, and scientific advisor at the CEPII.

It should be noted that the exchange of services, which represents a significant share of global trade, is not included in this study. “We placed all products on the same level, even though a particular good that is more important for a country’s economy could have a greater impact on the ultimate choice of money,” Coquidé admits. “We could also consider that an export tie is worth more than an import tie, as it is the seller who determines the exchange currency.” A number of parameters are therefore missing. “This is why we will soon introduce other sources of data to enhance the model: direct foreign investment, local treaties, different economic sectors, financial flows, and value chains,” indicates Lages. “The supremacy of the dollar is not solely due to its use in transactions,” reminds Tadjeddine-Fourneyron. “If this were the case, we would expect the yuan to rise faster given China’s importance in trade.”

Numerous other mechanisms maintain the greenback as the international currency of reference. First, a money’s value stems from the confidence the community places in it. “China is increasingly imposing the yuan as the billing currency for payments it is involved in. However, when that country is not involved in a transaction, the dollar or the euro are still preferred. A resistance to accepting the yuan therefore prevails, which can be explained by economic and especially political reasons. For example in Vietnam, where fear of the big neighbour is real, bitcoin is better accepted than the yuan," the scientist adds.

The dollar and its exorbitant privileges

Reserve value, which is essential to an international currency, should also be taken into account: “For now, BRICS countries have made no advanced proposals to perform this function,” believes Grekou. “In addition, there is currently no benefit in having exchange reserves in yuan, far from it, for such reserves would expose countries politically and economically to Chinese authorities.”

Massively boosted by the US central bank (FED) and the attractiveness of the American financial marketplace, capital flows – still essentially in dollars – also play a major role in this supremacy. “China has become an international financial player through its banks and sovereign funds, which now provide credit to numerous countries. However, Chinese banks remain highly dependent on the decisions of the Chinese political regime. As a result, BRICS member states are still very much contingent on financial capital denominated in dollars or euros,” Tadjeddine-Fourneyron says.

The United States also enjoys an “exorbitant privilege”, which allows it to monetise its debt. “However, some countries, such as China, believe that this privilege no longer holds given the loss in US power,” Grekou affirms. This challenge is one of the reasons why a number of nations have envisioned creating a new currency, with a view to having some weight within today’s international monetary system. On the practical level, the abandonment of the dollar as a currency of reference would also be a return to logic. “Convertible money has nothing to gain by going into the exchange market, as it has to pay a charge to convert into dollars, and then another to convert dollars into the destination currency for purchases,” he stresses.

The rise in power of BRICS countries and their potential currency will depend on the strategy they adopt. “The BRICS+ (Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Ethiopia, and Iran joined the network on 1 January 2024) have already shown a desire to base the new money on a lasting element: energy. However, in becoming major energy suppliers, BRICS states can decide whether this energy will be sold in their common currency. In that case, it would be thrust overnight into the limelight,” Grekou points out. However, control over trade also entails leadership in certain key sectors such as high technology, which China does not control for the time being. “What’s more, everyone has invested so much in the dollar, that if it lost its value too quickly, everybody would be negatively impacted.”

Finally, the United States will still be keen on conserving its supremacy. “It will not hesitate to offer monetary arrangements to satisfy those countries that might switch to BRICS,” Grekou supposes. “With this in mind, Joe Biden is already calling for the international monetary system to be reshaped.” The future therefore seems to hold in store a multipolar world, in which the dollar and the BRICS could share fiduciary domination.♦

- 1. CNRS / Université Paris Nanterre.

- 2. José Lages is the director of the Universe, Time-Frequency, Interfaces, Nanostructures, Atmosphere and Environment, and Molecules Institute (UTINAM –CNRS / Université de Franche-Comté). Célestin Coquidé is an associate researcher at the UTINAM, and a postdoctoral researcher at the LIRIS (Laboratoire d'InfoRmatique en Image et Systèmes d'information – CNRS / INSA Lyon / Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1). Dima L. Shepelyansky is a research professor emeritus at the Theoretical Physics Laboratory (CNRS / Université Toulouse III – Paul Sabatier).

- 3. “Prospects of BRICS currency dominance in international trade”, Applied Network Science 8, 65 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41109-023-00590-3

- 4. According to the UN’s Comtrade database: https://comtradeplus.un.org/

- 5. In this instance the researchers used the Standard International Trade Classification (SITC) Revision 4 https://unstats.un.org/unsd/classifications/Family/Detail/28

- 6. Currencies were once made out of precious metals, but that was not always the case. Sometimes, only the currency of lesser quality ultimately continued to circulate in the market. This could be due to psychological reasons, since between two currencies of different value, we tend to prioritise the exchange of the less valuable one. This process of replacing one currency by another is known as Gresham’s law.

- 7. Bureau d'Économie Théorique et Appliquée (CNRS / INRAE / Université de Lorraine / Université de Strasbourg).

Explore more

Author

Specializing in themes related to religions, spirituality and history, Matthieu Sricot works with various media, including Le Monde des Religions, La Vie, Sciences Humaines and even Inrees.