You are here

A Leap Forward for the Heritage Sciences

The CNRS and the IPANEMA1 platform, in collaboration with the French Academy of Sciences, are organising the World Meeting on Heritage, Sciences and Technologies, under the aegis of the Interacademic Group for Development (GID).2 Is this a first?

Loïc Bertrand: It is indeed. The fact that we are holding the meeting in the brand new auditorium of the Institut de France is no coincidence. Catherine Bréchignac, perpetual secretary of the French Academy of Sciences,3 immediately suggested that we co-organise the event, which testifies to the recognition of research on ancient materials, a disciplinary field that has gained momentum over the years. For us, this was a special moment that highlighted collaboration between laboratories and the emergence of a generation of researchers using innovative resources. It was an opportunity to review scientific advances in research on ancient materials in the fields of archaeology, palaeoenvironments, palaeontology and cultural heritage, as well as to identify emerging issues and foster their development.

How was the meeting organised?

L. B.: It consisted of three main events: a two-day scientific symposium (14-15 February), a series of round tables open to the public (16 February) and, simultaneously, six workshops organised in the Paris region, each focusing on a specific topic. The aim of the open day was to compare scientific, economic, societal, political and other perspectives on the subject of heritage. Indeed, for the GID, the latter is a lever for economic and social development. Heritage is, from this point of view, something very much alive. Several major players took part in the symposium. To name but a few, we welcomed Piero Baglioni from the University of Florence (Italy), a pioneer in innovative treatments for restoring heritage using nanostructured gels, Katrien Keune from the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (the Netherlands), a specialist in the physico-chemical mechanisms causing the deterioration of Flemish paintings, and Uwe Bergmann, a US physicist who is developing new instruments to study the composition and biochemistry of fossils, using X-rays. Around twenty speakers from the CNRS and various related laboratories took the floor, highlighting the CNRS’s expertise in research on ancient materials.

The meeting also provided an opportunity to reflect on the way in which the heritage science community is organised. Today, for example, the ‘Ancient and Heritage Materials’ major area of interest, a network we coordinate in the Île-de-France (Paris) region, brings together 733 scientists from 95 laboratories. Research on ancient materials therefore relies on a vast network that drives essential interdisciplinarity, but at the same time raises issues of organisation, information sharing and training.

What are the main global challenges when it comes to fostering research on heritage materials?

L. B.: I'd like to mention three priorities. The first is to get better support. The European Commission, with the backing of the European Parliament, has announced that heritage will be back among its research priorities for 2021-2027, the first time this has happened since the 5th Framework Programme twenty years ago! In a still-recent past, heritage wasn’t regarded as ‘serious’ science, even though there was an increasing number of groundbreaking discoveries, together with very high public interest. A second priority is to forge international collaborations around specific objects, collections and sites. There is a need for better coordination between research and exhibitions in leading museums, and for greater involvement in important archaeological excavation projects.

And lastly, the third priority is interdisciplinarity, which is crucial to the study of heritage. Having such a multidisciplinary community enables us to bring together researchers from fields as diverse as art history, physics, mathematics and social sciences. For instance, direct collaboration with the digital humanities touches on the law, the status of data, how it can be used, good practice, and so on. Any progress achieved could also be transferred to other sciences. Heritage is a real interdisciplinary hotbed!

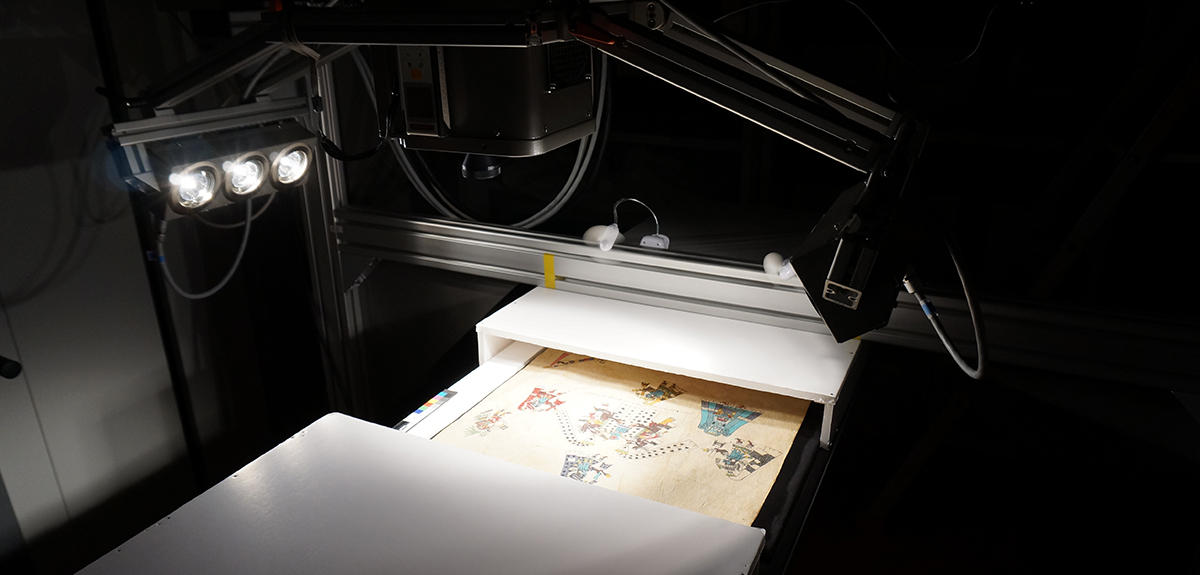

Research on ancient materials is undergoing a profound transformation, particularly through the development of new methods in such areas as imaging, with the use of 3D scanners, lasers and large-scale facilities....

L. B.: In our field, hyperspectral imaging is a revolutionary technique that emerged around twenty years ago and has taken on huge importance. It enables us to study fossils and paintings, combining information about composition and form. Coupling these two types of data makes it easier to interpret very complex, aged and degraded systems, allowing us to more rapidly identify the key points to be studied. We believe that future data mining methods will play a key role in improving our understanding of such things as degradation mechanisms or the shapes of fossil organs, as well as in identifying features and clues that help to establish authenticity.

You represent France (together with Isabelle Pallot-Frossard4) in the European Research Infrastructure for Heritage Science (E-RIHS), whose team attended the World Meeting. Can you tell us more about this platform?

L. B.: The E-RHIS, which will be operational from 2022, aims to bring together large-scale characterisation facilities such as synchrotrons, microscopy, lasers and dating instruments, as well as mobile instrumentation, and connect them all to databases and archives. This platform addresses a need for simplification. For example, if a museum wants to study an important collection, there is at present no common entry point to European resources. A research team has to apply for as many characterisations as there are instruments. The E-RIHS will provide this common access. The aim is also to be able to support long-term schemes, such as museum collections, ambitious exhibition projects and on-site work, with large national or international consortia. Once the programme is selected, the E-RIHS will provide integrated access to a wide range of infrastructure in Europe.

The question of skills is also central to the E-RIHS, since users of the facility are not only looking for tools but people. At the World Meeting, we drew the attention of organisations and universities to the fact that expanding this field of research requires the development of new professions. In some European countries such as France, Italy, Spain and Greece, collections are so extensive that work will be carried out at both national and European levels. However, the goal is to have a platform where priorities and the development of facilities are discussed in a concerted fashion, so as to avoid duplication and provide more suitable resources.

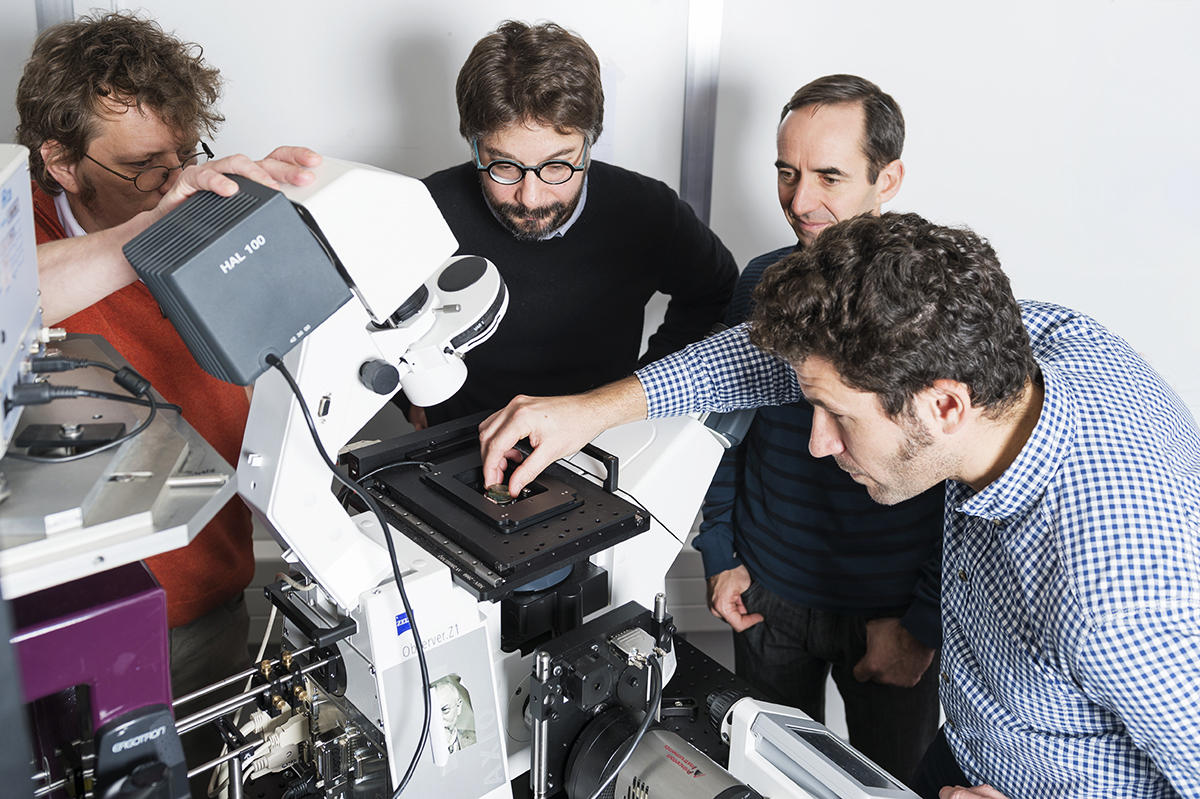

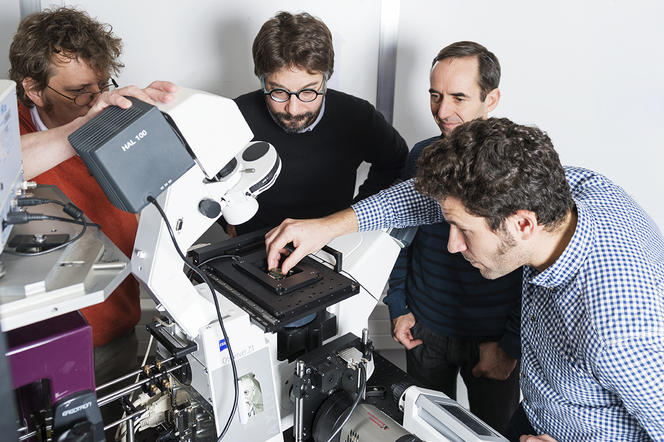

You also head the IPANEMA platform, which supports researchers wishing to carry out materials analysis using the SOLEIL synchrotron. How will it contribute its experience to the E-RIHS?

L. B.: The IPANEMA is an unconventional organisation connected to the creation of the SOLEIL synchrotron,5 which the CNRS and its partners wished to open up to a number of scientific domains such as heritage research. The platform has a specific operational mode in that it undertakes a considerable amount of methodological research and development of new tools and resources. By hosting colleagues on the basis of a scientific project, it helps the community, and especially young scientists, to train in synchrotron methods. In some ways, the organisational issues that the E-RIHS is facing are ones that we have already dealt with at the IPANEMA. This should enable us to use our experience to optimise the development of E-RIHS.

- 1. Institut Photonique d'Analyse Non-destructive Européen des Matériaux Anciens (CNRS / Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines / Ministère de la Culture).

- 2. Chaired by François Guinot, the Interacademic Group for Development (GID) is an international network created in 2007 by eleven academies in Southern Europe and Africa.

- 3. A former president of the CNRS, Catherine Bréchignac is also a delegate ambassador for Science, Technology and Innovation.

- 4. Art historian Isabelle Pallot-Frossard has been director of the Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France since 2016.

- 5. For “Source Optimisée de Lumière d’Énergie Intermédiaire du Lure” (Laboratory for the use of electromagnetic radiation).