You are here

A Historical Treasure Bordering Ancient Mesopotamia

“The first excavations were perplexing!” This was not ArScAn1 researcher Aline Tenu's first archaeological mission in the Middle East, yet the discovery that she made with her colleague in Iraqi Kurdistan continue to yield many surprises. “You could call it a small revolution,” confirms their colleague Philippe Clancier, an epigraphist at ArScan.

What exactly did they find? Over the course of six excavation campaigns, conducted between 2012 and 2018, the archaeologists unearthed the traces of an unexpected ancient city at the site of Kunara. It is located on the outskirts of the Zagros Mountains, on two small hills overlooking the right bank of a branch of the Tanjaro River, approximately 5 km southwest of the city of Soulaymaniyah (modern-day cultural capital of Iraqi Kurdistan). “This area near the Iran-Iraq border was not very well explored until now,” Tenu points out. The ban on venturing into Kurdistan under Saddam Hussein’s regime as well as successive wars—the most recent against ISIS—did not make things any easier. “The situation is much more favourable now,” enthuses the archaeologist, emphasizing the warm support offered by local authorities.

An unexpected discovery

This discovery is all the more unexpected as Kunara is a rare find. Five excavation sites have unveiled large stone foundations stretching dozens of metres, in both the upper and lower parts of the site. They apparently date from the late 3rd millennium, circa 2200 BC. In other words, monumental structures were erected over 4000 years ago. “We weren’t expecting to discover a city here at all,” admits Kepinski, who initiated the mission before handing it over to Tenu.

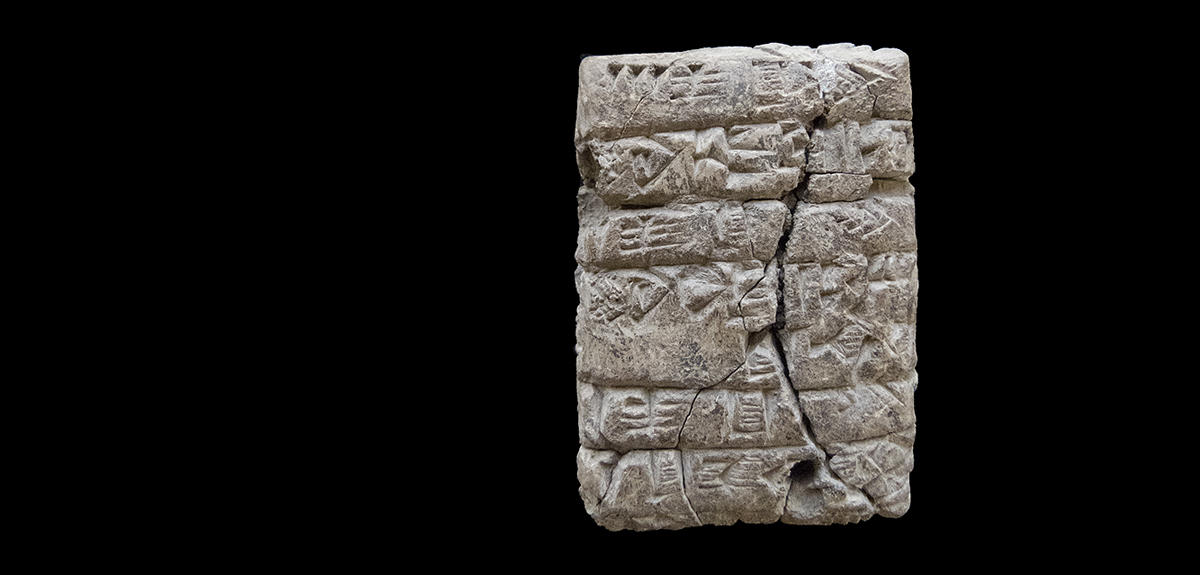

One morning in 2015, the ground beneath these structures that date back multiple millennia offered new surprises. “One of our partners said breathlessly ‘We found a tablet!’” Tenu recalls, filled with emotion. It was followed by dozens and dozens of others, in the shape of small clay rectangles approximately 10 centimetres on each side. They were all inscribed with closely-spaced cuneiform signs, which is to say in the shape of nails and wedges. There was no doubt, these were the same traces of writing that appeared in the Middle East in the middle of the 4th millennium BC, and that make this region the universal cradle of writing and history. Over 4000 years ago, the inhabitants of Kunara were part of this very small group of peoples who had already become a part of history!

This was nevertheless not the stuff to shake the foundations of the hushed and richly-endowed world of Assyriology. Born in the mid-19th century2 oriental archaeology has more than one legendary discovery among its excavations, including Babylon, Nineveh, Nimrud, and Ur, to cite just a few. All of these legendary cities continue to impress through their excessiveness and architectural audacity, in addition to their teeming sculpted bestiary full of chimeras—part human, part bull—standing watching over imposing palaces surrounded by labyrinths of small streets. All of these ancient cities spread between the Tigris and the Euphrates, the “land between the rivers” known as Mesopotamia.3 Aside from their evident wealth, these archaeological sites have two exceptional distinguishing features: they are the oldest known cities, and as far as we know, humanity’s first city-states. Most importantly, it was within their walls that writing and the first literary forms were perfected, such as the legendary adventures of Gilgamesh.4 In comparison, during the same period the peoples of Western Europe were at best erecting dolmens or a few monoliths, without leaving the least written trace.

At the gates of Mesopotamia

What can the few hundred metres of Kunara’s stone foundations and its modest written traces add to this prestigious list of archaeological and literary treasures? “The city of Kunara provides new elements regarding a hitherto unknown people that has remained at the periphery of Mesopotamian studies,” enthuses Tenu. The city of Kunara could prompt Assyriologists to reconsider this mountainous region, whose history has until now been written by a single hand, that of the Mesopotamian conquerors.

This city was located on the western border of Mesopotamia, at the gates of Mesopotamia’s first empire, known as the Akkadian Empire, which united all of the city-states in the region. It was ruled by some of Mesopotamia’s greatest kings, who bore the laudatory title of “King of the Four Regions of the World.” A military victory won by one of these kings—Naram-Sin, grandson of the founder of the Empire—was immortalized on a stele of pink limestone that is exhibited at the Louvre Museum. “Naram-Sin is depicted triumphing over this people of the mountains, the Lullubi,” Tenu explains. In the exclusively Mesopotamian sources available today, the Lullubi are depicted as “barbarians” living secluded in the mountains. Nothing more than that was known.

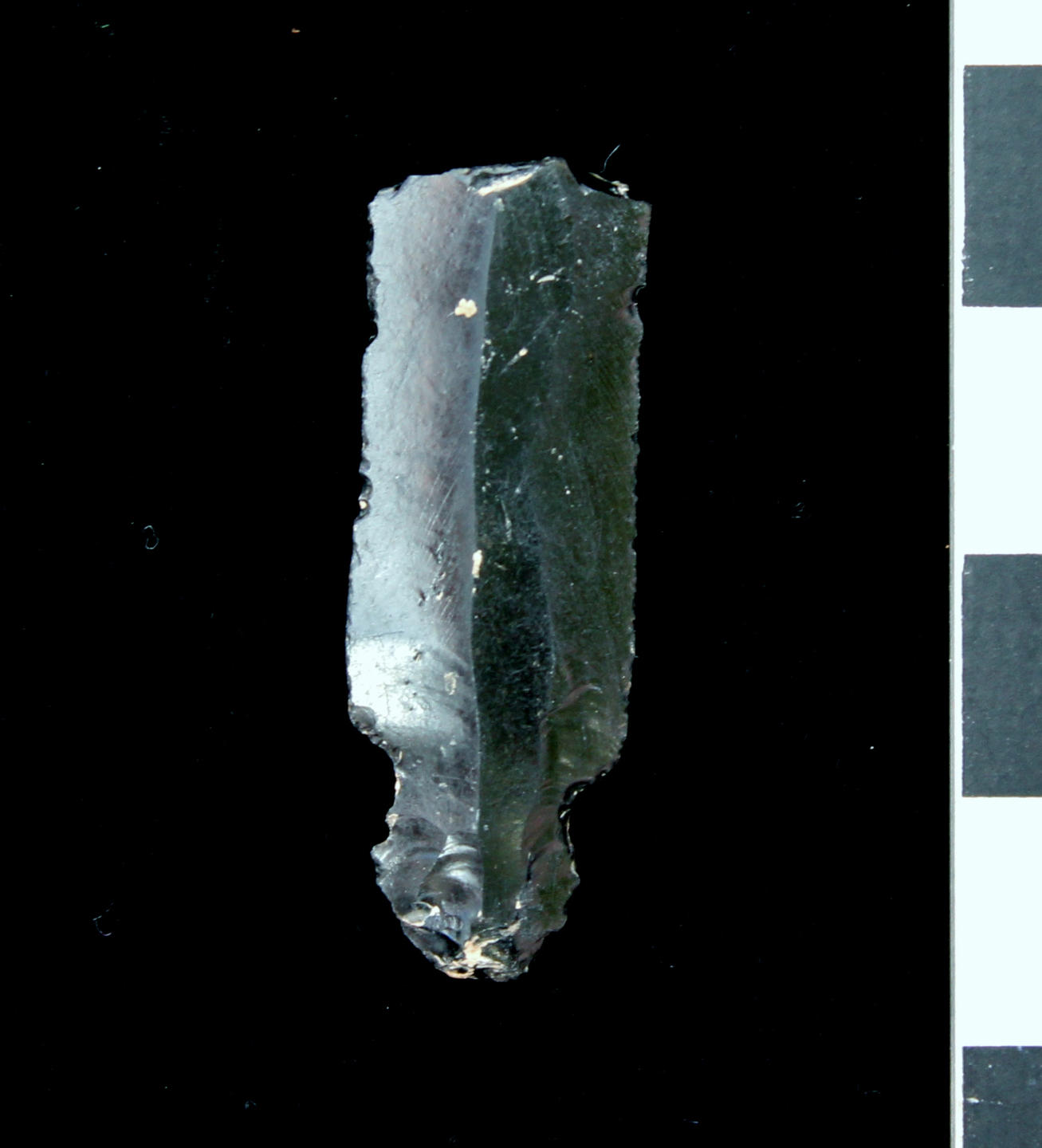

The discovery at Kunara shines a new light on this people. “It is possible that this city was one of the capitals of the Lullubi,” suggests the archaeologist. If this theory is confirmed, the history of the Lullubi would take on an entirely new scope, for far from living isolated from the world, the inhabitants of Kunara maintained commercial relations with very distant regions in both the east (toward Iran) and the north (toward Anatolia and the Caucasus). These links are attested to by the presence of various types of lithic tools (obsidian, basalt, carnelian) for which there are no nearby deposits. “The city must have even been fairly prosperous,” Tenu suggests, “as rare stones such as obsidian were used to produce entirely commonplace tools.” This openness toward the world and affluence is also illustrated by the presence of a number of moulds for metal blades. Kunara and its inhabitants were therefore full participants in the Bronze Age, which had begun a few centuries earlier in Mesopotamia.

Power based on commerce and agriculture

Connected to these tools and a profusion of ceramics—with some fragments handsomely adorned with zoomorphic patterns—is an entire series of unexpected fauna that once walked the earth in Kunara. The bones of bears and lions, which were prestigious wild animals at the time, attest to royal hunts or reverent gifts. The remains of two horses, an exceptional mount for the 3rd millennium, also confirm that Kunara was far from a peripheral area. “The city most likely took advantage of its strategic location on the border between the Iranian kingdom in the east and the Mesopotamian kingdom in the west and south,” suggests Kepinski.

However, it was surely the area’s agricultural wealth that promoted its rise. Archaeologists have discovered the remains of goats, sheep, cows, and pigs, suggesting the existence of a major livestock farming system. The presence of an irrigation network in the city’s south is also a reminder of the mastery the region’s inhabitants achieved in grain farming, especially barley and malt.5 For that matter, it is the inner workings of this agricultural economy that the scribes of Kunara engraved on the dozens of tablets found at the site. “They had a firm grasp of Akkadian and Sumerian6 writing, as well as that of their Mesopotamian neighbours,” emphasizes Clancier, a specialist on cuneiform writing. “The first tablets found in a building of the lower city, register a large number of entries and departures of flour,” he continues. “It was actually a kind of flour office,” Tenu adds, “in all likelihood for the benefit of the ‘Ensi’ of Kunara.” The title of Ensi signifies both “king” and “governor.” Its mention in tablets, in addition to the title of Sukkal—a senior state dignitary—evoke a political administration based on the Mesopotamian model. A simple borrowing from its powerful neighbour, or a mark of submission to the Akkadian Empire? “It’s still too soon to know,” Tenu prudently says. “It could also be a hybrid organisation that was built over the course of successive annexations and independences.”

A language and writing of its own

This is incidentally what is suggested by the second group of tablets discovered in 2018, once again in the lower city, but in a different area. It is no longer a question of flour, but most certainly of grain, a much more valuable crop: “The tablets provide information about considerable warehouses, some reaching over 2000 litres,” Clancier ventures. These important volumes confirm sustained agricultural activity and large-scale gathering conducted by a major city. Yet it is the unit in which they are referred to that is surprising. “It is not the Akkadian imperial Gur,7 but rather the Gur of Subartu, or literally the Gur of the North,” the epigraphist points out. This is a new and unique unit, attested only at Kunara: “The use of an original unit could resonate like an act of independence,” Tenu suggests.

Another interesting element is that the tablets are brimming with points of origin, such as “Khabaya” or “Ninarshuna,” providing a list of names that is entirely new for Assyriologists. “While they are written in cuneiform, these names do not sound Mesopotamian,” Clancier confirms. Kunara and its surrounding region had its own appellations and language. The only regret is that to date, no tablet or inscribed brick has revealed the city’s original name. “But we will continue to look,” Tenu says with delight, her eyes already on the next excavation campaign scheduled for the autumn of 2019. New discoveries could help resolve unanswered questions. Who exactly were the inhabitants of Kunara? Were they even Lullubi? If not, who were they? And most especially, why did this city not spring back to life after the violent fire that apparently ravaged it over 4000 years ago? Let us hope that it will ultimately reveal the name it was given by this ever-mysterious mountain people.

- 1. laboratoire Archéologies et sciences de l’Antiquité (CNRS/Inrap/Ministère de la Culture/Université Panthéon-Sorbonne/Université Paris Nanterre/Université-Vincennes-Saint-Denis).

- 2. Assyriology began in 1842, when the French governor Paul-Emile Botta had monumental sculptures, in addition to one of the gates of what was the palace of Khorsabad (1st millennium BCE), unearthed from the semi-arid plains of northern Kurdistan.

- 3. As it was literally referred to much later by the Greeks of Antiquity, meso meaning “between,” and potamos meaning “the rivers.”

- 4. The exploits of this hero, king of Uruk (start of the third millennium) were described in a story, written in Akkadian during the 18th and 17th century BC.

- 5. Malt was notably used to produce beer.

- 6. 6. Akkadian, the first Semitic writing, is a syllabary version derived from Sumerian cuneiform pictograms; the two languages were mixed for a long time in Mesopotamia.

- 7. One Gur equalled 300 litres.