You are here

Presenting the world's oldest architectural plans

05.25.2023, by

Engraved on stones and dated to 8,000 and 9,000 years ago, the oldest known plans to scale have recently been published in the journal PLOS ONE. They depict gigantic prehistoric structures known as “desert kites” that were designed to trap wild animals, and were discovered in the deserts of Jordan and Saudi Arabia by researchers from the Archéorient laboratory (1) and their colleagues.

This work was carried out as part of several international excavations including the “Globalkites” project, led by the CNRS researcher Rémy Crassard since 2013. It features in a paper published on 17 May, 2023 in the journal PLOS ONE(link is external).

1

Slideshow mode

One of the excavation sites is located in southeastern Jordan, on the arid and remote Jibal al-Khashabiyeh plateau.

SEBAP & O. Barge/CNRS

2

Slideshow mode

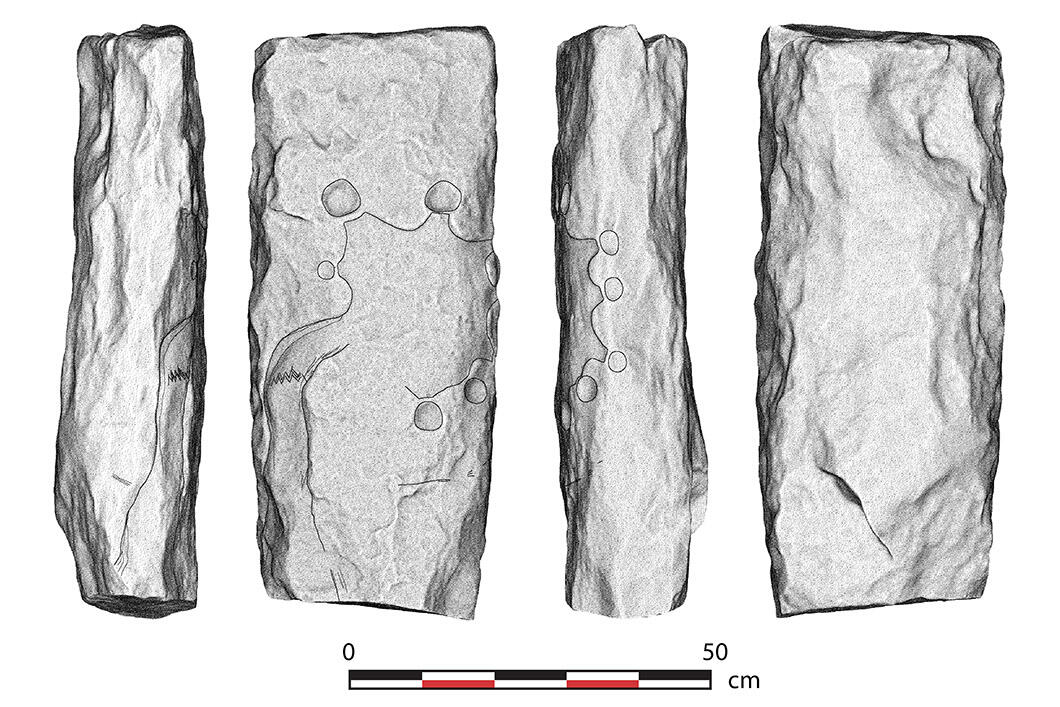

It was on this monolith at the Jordanian site that researchers identified the oldest architectural plan ever discovered. It was engraved about 9,000 years ago on this limestone block, which weighs 92 kg and is around 80 cm high, most likely using a stone tool such as a burin or a flint flake.

SEBAP & Crassard et al. 2023 PLOS ONE

3

Slideshow mode

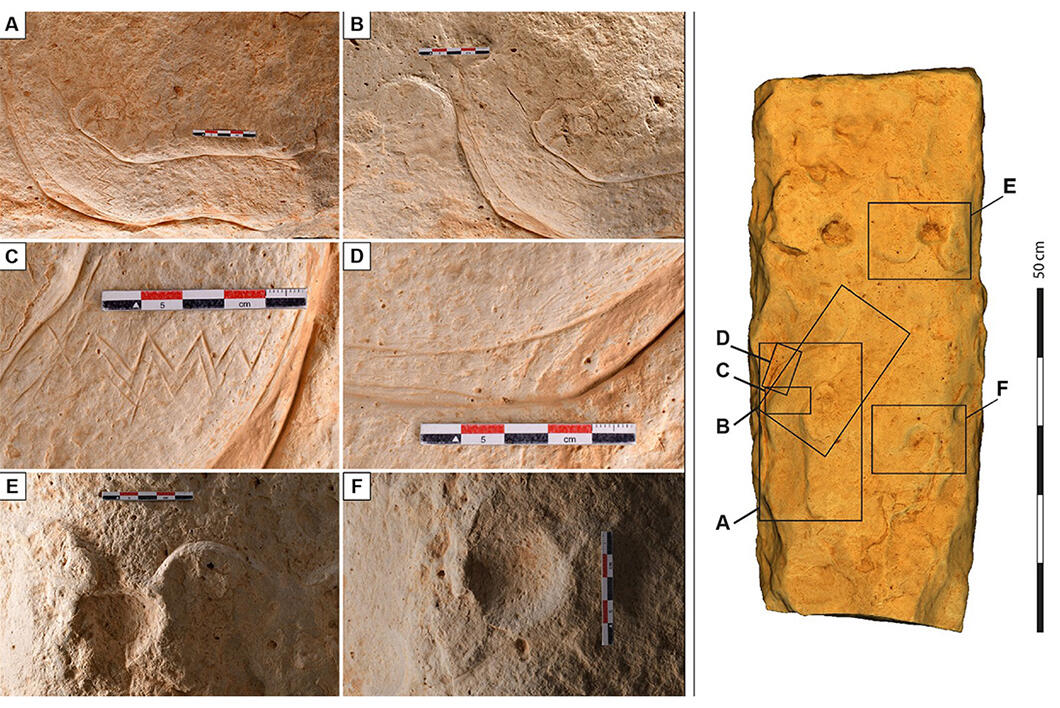

On this 3D model of the monolith the researchers produced an interpretative drawing (which can be clearly seen in the second image from the left). This represents the plan of a gigantic prehistoric structure designed to trap wild animals. Such structures, called desert kites because of their shape, generally have three features, as in this drawing: a corridor (seen in the lower part of the image) leading to a large enclosure surrounded by a number of pits (the small round shapes in the drawing).

SEBAP & Crassard et al. 2023 PLOS ONE

4

Slideshow mode

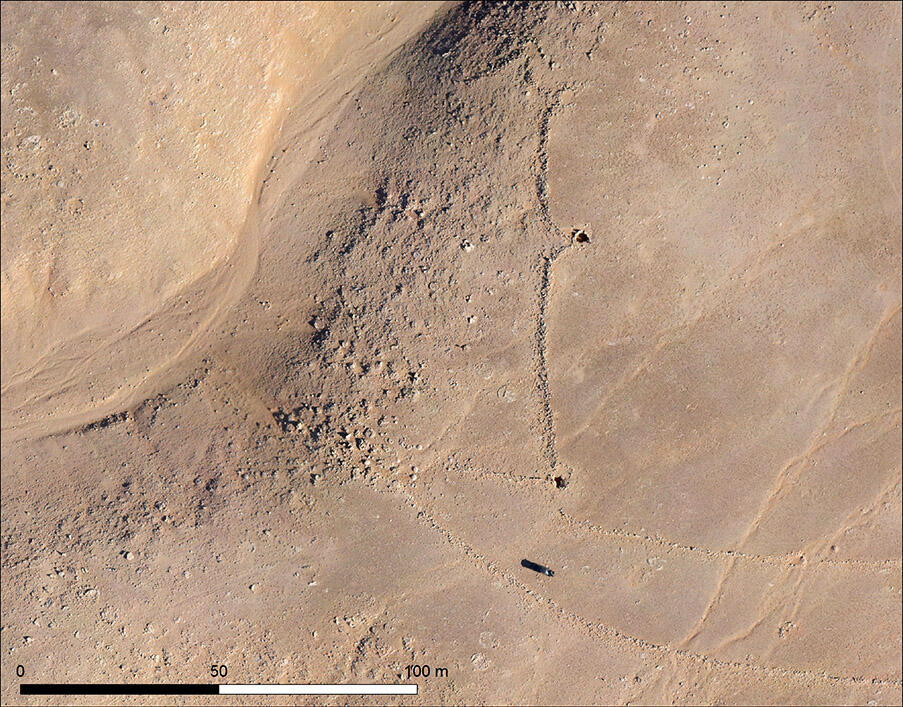

This aerial view shows part of the kite's vast enclosure and the small pits surrounding it, the plan of which is engraved on the monolith. According to the researchers, the ability to transpose such a large area onto a small surface represents an important step in the intellectual development of humans.

SEBAP & O. Barge, CNRS

5

Slideshow mode

The archaeologist Wael Abu-Azizeh, co-author of the paper, seen examining an excavated pit in the Jordanian desert kite. The pits, of which there are around ten in the enclosures in this region, have an internal wall reinforced by stone facing, and were sometimes dug down to a depth of as much as two metres below the surface.

SEBAP & O. Barge /CNRS

6

Slideshow mode

In addition to being to scale, the plan engraved on the monolith (right) includes several very precise details carved in bas-relief to a depth of 0.5 to 1 cm (left thumbnails). These include fine incisions (especially to delineate the contours of the kite), scraping and pecking.

SEBAP & Crassard et al. 2023 PLOS ONE

7

Slideshow mode

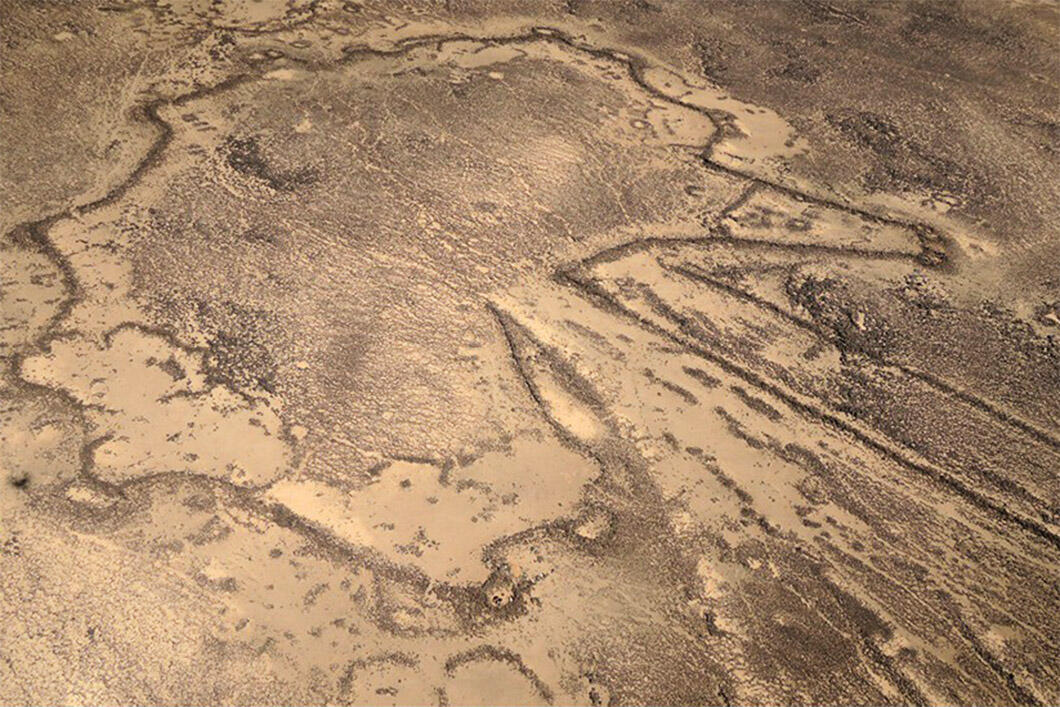

In another Jordanian desert kite, a kind of path can be seen on the right, marking the convergence point of walls several kilometres long, that the animals followed all the way to the large enclosure, from which they then fell into the pits placed all around it.

E. Régagnon/CNRS

8

Slideshow mode

The archaeologists also worked at a site in northern Saudi Arabia. There, in a dried up river bed (wadi) that cuts through the plateau of Jebel az-Zilliyat, they found another engraved block (indicated by the circle) that proved to be of great significance for their work on desert kites.

Crassard et al. 2023 PLOS ONE

9

Slideshow mode

The block found in Saudi Arabia, which had fallen off the edge of an overhanging cliff, features an engraving also described by the researchers and that they date to around 8,000 years ago. The engraving is much larger than the one found in Jordan, and is drawn on the flat surface of a massive sandstone block about 4 metres long.

Crassard et al. 2023 PLOS ONE

10

Slideshow mode

The Saudi engraving actually depicts two kites, an aerial view of one of which is shown here. More than 6,600 desert kites have been discovered to date in regions ranging from Kazakhstan to Saudi Arabia.

O. Barge/CNRS

11

Slideshow mode

Until now, only a few schematic representations of desert kites were known. Those recently analysed by Rémy Crassard (right), Jacques Élie Brochier (left), Wael Abu-Azizeh, Olivier Barge and their colleagues, were engraved with very great precision. They bear witness to a widely underestimated ability to master spatial perception at such early times, when neither writing nor mathematics yet existed.

O. Barge/ CNRS

Explore more

Society

Article

02/13/2026

Article

02/10/2026

Article

01/23/2026

Article

12/02/2025

Article

11/09/2025

Archaeology

Article

09/29/2025

Article

04/21/2025

Article

04/16/2025

Slideshow

11/08/2024

Article

10/31/2024