You are here

No social distancing in borderless Amazonia

This post is published in partnership with the COVIDAM blog, produced by the international research laboratory iGLOBES)1 and the Institute of the Americas (IdA).2

What would have happened if Covid-19 had appeared in the Amazon rainforest 1,000 years ago? For an archaeologist, this is a question worth considering. Indeed, like its counterparts in Africa and Asia, the humid jungle of Amazonia is a potential hotbed of unknown viruses that only need a chance to hatch before spreading around the globe. All ecosystems that have been transformed by human activity are susceptible to the development of new diseases. The incredible diversity of life forms in tropical zones further increases the risk of unexpected zoonoses (infections of animal origin) suddenly emerging from South America’s vast forest regions. The agents conveying such poisoned gifts are just as varied, ranging from voracious vampire bats silently biting their prey at night to vertebrate game species coveted for their tasty meat, or even a sweet little animal adopted as a pet, like a monkey or a parrot, which could be carrying a deadly microbe.

Lockdown in the backwoods

It is safe to presume that the earliest inhabitants of the Amazon forests have experienced zoonotic epidemics in the time since their arrival some 13,000 years ago – and that attentive observation of the spread and evolution of these diseases led them to discover effective remedies. The Amerindians are past masters in the preparation of pharmacopeias based on plants and other natural substances, and their millennia-long occupation of the lowlands has given them plenty of time to develop a remarkable body of environmental lore. Even today, Western pharmacologists regularly come across effective remedies developed by native populations without being able to identify the key active ingredients due to the complexity and precision of their formulation. With nearly 40,000 endemic plant species, the Amazon Basin has offered Amerindian savants a richly equipped outdoor laboratory. Furthermore, every part of any plant is potentially useful in the composition of a therapeutic recipe: flowers, fruits, leaves, stems, roots, bark, sap, moss, tendrils…

How would they have reacted to an unprecedented contagion? Quite probably in the same way as they are reacting to Covid-19 today. Seeing the disease spread like wildfire from one individual to another, they would have concluded that inter-community relations, normally vital to their social equilibrium, constituted a mortal danger under the circumstances. In a bid to halt transmission, they would have isolated themselves and sealed off access to their village in order to prevent any outsiders from entering. This is what many ethnic groups in the region are doing today to protect themselves against SARS-CoV-2 and Covid-19. In Ecuador, for example, the Kichwa and the Chicham Aents have implemented this radical solution, blocking the trails leading to their settlements with huge logs and standing guard, ready to fight off anyone trying to force their way through. In other words, they have opted for a lockdown as their primary protection against infection, like most countries in the world.

However, seeing that this was not sufficient and that they also needed to care for those who had contracted the disease, they would have set about creating an appropriate pharmacopeia. For lack of effective Western medication, this is what the Amazonian natives of 2020 have done. There would have been discussions among shamans, symptom surveys, trials of medicinal compositions and tests on patients. Various modes of application would have been experimented, by infusion or fumigation, along with extracting the disease by magic or by performing tried and tested incantations.

Before ending up on the road to death, the Amerindians would probably have called on the spirits and other beings from beyond, to seek their guidance and learn recipes for potions. In short, they would have done what they knew to be effective: avoiding contagion, experimenting with remedies and consulting as many humans and non-humans as possible. To put it another way, they would have interacted with invisible entities and the environment that spawned the viral danger in order to assuage the discord with nature and restore a harmonious interaction.

All roads lead to the Amazon

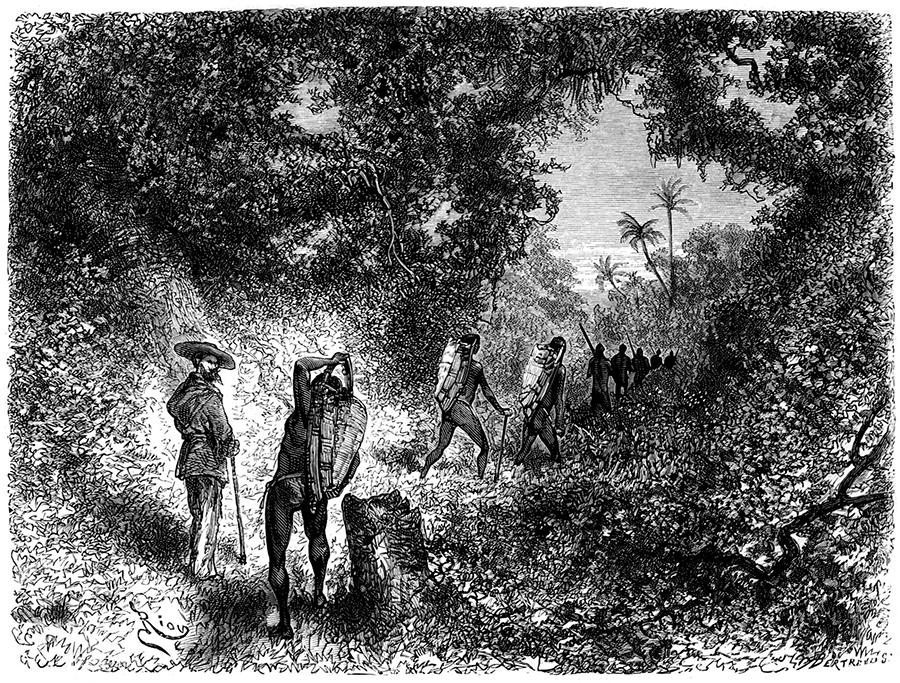

How could such an epidemic have spread? Quite simply by hitting the trail. The fact is that, contrary to a persistent preconception, the canoe is not always the preferred means of transportation among Amazonian natives, many of whom are actually poor mariners. On the other hand, these forest dwellers are first-rate hikers. Constantly on the move, they walk rapidly from place to place. Moreover, the region is crisscrossed by thousands of heavily travelled trails, unimpeded by any geopolitical borders. Which belies another cliché, that of the impenetrable jungle through which any traveller has to hack their way with a machete, slowly clearing a path through a mass of stinging plants and brambles. The Amerindians have established a well thought-out circulation network, ranging from narrow winding paths to wide, clear, expertly laid-out roads (as in the Xingu region).

These trails mainly connect villages and serve a number of purposes. Most importantly, they are used to circulate and visit other settlements. In fact, it is surprising to see the extent to which the “sedentary” Amerindians actually lead a semi-nomadic lifestyle. Any reason is good enough for setting off on a trip: to hunt, to gather certain substances or materials, to visit relatives or friends, to barter goods, observe a ceremony, fight a battle, form an alliance, etc. Finding someone at home is always a gamble as there is a good chance that they have taken off somewhere.

In the past, this trail network was even more developed, in particular for exchanging objects and products that could only be sourced or made by certain people. Many thoroughfares were reserved for specific functions. For example, in the 18th century the Wayana people of the Guiana Highlands controlled their land with military organisation. They built a wide, 200-kilometre road, cutting north to south across the watershed divide, to monitor movements in their territory. Every 10 kilometres they erected a palisaded village with watchtowers manned by sentinels so that, at the slightest alarm, they could quickly assemble their forces along the road to fend off an external attack.

In southwest Amazonia today, the ring villages comprise large collective houses arranged in a circle around a vast ceremonial ground. Radiating out from these settlements are multiple trails of different sizes and functions, winding pathways used for everyday activities as well as perfectly straight roads as much as 40 metres wide dedicated to ritual travel.

Barter, barter everywhere

Judging from the archaeological data, this road-building frenzy was even stronger before the arrival of Europeans. Nearly everywhere in Amazonia, researchers have identified traces of an extensive web of carefully built pathways. They include elevated routes across the flood-prone savannahs of Venezuela and the Llanos de Moxos in Bolivia. In other places the lanes are carved into the earth. The most impressive examples are found in Ecuador’s Upano Valley and date back at least two thousand years. Reaching up to 10 metres in width and three metres in depth, they go on for kilometres, linking important sites marked by artificial mounds. Very recently, in the Brazilian state of Acre, the archaeologists Sanna Saunaluoma and Eduardo Neves unearthed ring villages on low mounds dated at 1300-1600 AD, from which wide trails branch off in all directions, leading to other similar sites.The pre-Columbian world thus developed in a context of constant movement characterised by frequent and extensive bartering. Amazonian societies were much less insular than is commonly thought. Inter-ethnic marriages and the integration or merging of different groups contributed to this momentum. As a result, new traits and exogenous particularities were easily adopted.

This ongoing interaction would have facilitated the dissemination of infectious diseases. A zoonosis would have flourished through these contacts. It is probable that the emergence of such a contagion would have terrified the populations, whose first reaction would no doubt have been to close off their roads and trails, voluntarily isolating themselves while concocting a treatment. And had these measures proved ineffective, they would certainly have fled their territory in search of a plague-free land.

The void without Covid

Thinking about it, the Amerindians have in fact experienced all of these symptoms 500 years ago, not due to a tropical zoonosis but because of common Western diseases for which they had no antibodies. They already suffered an epidemiological disaster with the arrival of the Europeans. As Tzamarenda, chief of the Shuar of Ecuador declared in March 2020, “We have already been struck by pandemics – such as the flu, measles and chickenpox – that have killed millions of people in Latin America.” The European conquest of the early 16th century set off an epidemiological bomb that triggered widespread chaos in the Amerindian world. The depopulation in those first years was appalling, with an estimated 85 to 90% of the peoples of Amazonia succumbing to imported diseases.

The natives had identified the origins of these new and devastating illnesses and their connection with the bartered goods that they obtained from the Europeans. In the case of the Yanomami, the anthropologist Bruce Albert emphasises that they attributed certain epidemics to “metal fumes”: the smell of the anti-rust grease on the new machetes for which they entered into contact with outsiders, at the risk of contamination. Breathing poisoned air from others’ exhalations and having to accept the danger of contracting a disease in order to acquire desired goods – their plight strangely resembles the present situation.

Today the Amazonian populations are once again going through the same nightmare, with a mortality rate twice that of the rest of Brazil, exacerbated by the indifference of the national authorities. Especially vulnerable to pulmonary diseases, Amerindians were quickly struck by Covid-19, a reminiscence of the darkest days of their history, when they first came into contact with Westerners. In addition, the current pandemic has had a perverse collateral effect, in that the weakened communities are no longer able to resist the extortions of the henchmen of the large mining companies and food industry lobbies. The violation of the indigenous territories has become even more tragic since the emergence of the virus. Still, the Amerindians are no strangers to disaster, because, as pointed out by Chief Ailton Krenak in Brazil, they have been living through the apocalypse for the past 500 years.

And all through that time, the Amazon forest has been shamelessly burnt, casting the shadow of an environmental threat over humanity and heralding the possibility of further pandemics.

References

•Gibb Rory, David W. Redding, Kai Qing Chin, Christl A. Donnelly, Tim M. Blackburn, Tim Newbold and Kate Elizabeth Jones, 2020, “Zoonotic host diversity increases in human-dominated ecosystems”, Nature, 584: 398-402.

•Heckenberger Michael J., Afukaka Kuikuro, Urissapá Tabata Kuikuro, J. Christian Russell, Morgan Schmidt, Carlos Fausto and Bruna Franchetto, 2003, “Amazonia 1492: Pristine Forest or Cultural Parkland?” Science, 301: 1710-1714.

•Rostain Stéphen, 2017, Amazonie. Les 12 travaux des civilisations précolombiennes, Belin, Paris.

•Rostain Stéphen, 2020, Amazonie, l’archéologie au feminin, Belin, Paris.

•Saunaluoma Sanna, Justin Moat, Francisco Pugliese and Eduardo G. Neves, 2020, “Patterned Villagescapes and Road Networks in Ancient Southwestern Amazonia”, Latin American Antiquity, 31(4): 1-15.

The viewpoints, opinions and analyses expressed herein are the sole responsibility of their author(s) and cannot in any way be construed as reflecting the views of the CNRS.