You are here

Could Covid-19 Affect Public Trust in Science?

“Our actions are guided by one principle … and that is trust in science.” This sentence, pronounced by French president Emmanuel Macron in a recent address to the nation, raises an interesting question: what impact could the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus pandemic have on the way the French feel about science and technology? This is an opportunity to dismiss common beliefs and underline the importance of investigating recent evolutions in science and scientific expertise.

A trust in broad terms

Faced with the risks and uncertainties associated with the pandemic, all eyes turn to the research community. Every day, virologists, epidemiologists, infectiologists, immunologists, sociologists, etc., are invited to share their views in the press, on television, the radio, and the Internet.1 Many of the questions put to them are predictable: what is an emergent disease? A zoonosis? What makes the coronaviridae family different from other viruses? Scientists are also expected to answer some strange queries: was the coronavirus invented by the Pasteur Institute? Is there a connection between its propagation and the deployment of 5G? And so on. Epidemics have always been accompanied by rumours and “fake news”, and coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 is no exception. As a result, researchers have to perform two parallel missions in real time, giving information and debunking misconceptions.2

This scientific narrative circulates largely unimpeded, fuelled by the anxiety generated by the pandemic as well as the general public’s longstanding interest in biomedical research. Moreover, contrary to beliefs, including in the scientific community, it is underpinned by a trust in broad terms in France’s scientific institutions.

We must pay tribute to the perseverance of Daniel Boy, political scientist and research professor emeritus at the National Political Science Foundation (FNSP): France is the only country that conducts regular surveys on the public image of the sciences, an effort that began in the early 1970s (the next national edition will be published in 2021). A quick perusal of these reports is sufficient to quash any preconceived ideas about the French being distrustful. Even the high-profile scientific-technical crises that have arisen now and again since the 1970s have never lastingly lessened their faith. After the H1N1 crisis in 2011, 87% of those surveyed described themselves as “very” or “rather” trustful of science – much more so than of the media (29%) or the government (27%). And in the summer of 2019, while the Ebola virus was spreading in the Democratic Republic of Congo, a similar study conducted by Harris Interactive estimated the level of public trust at 91%3 – a record high.

Ambivalence on scientific applications

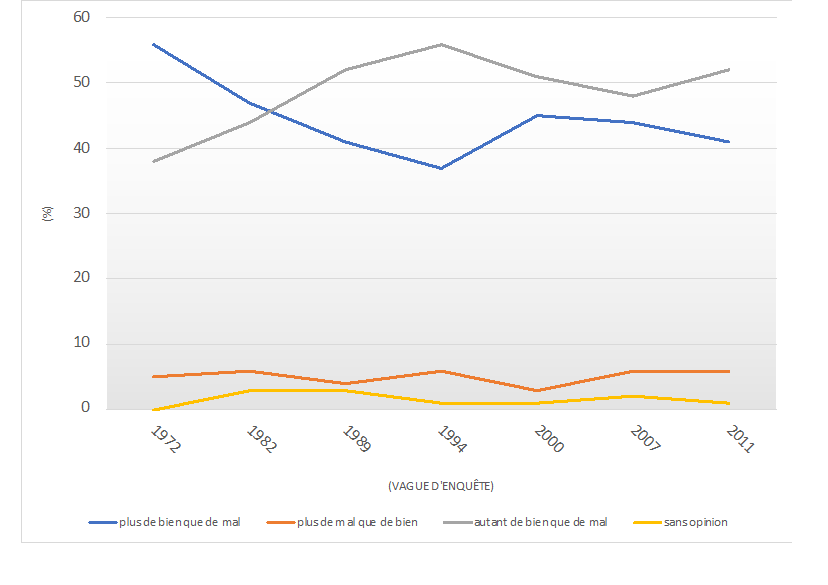

With the trust indicators all on high, why wonder now about the impact of the coronavirus? There are at least three reasons. First and foremost, because this narrow framework in terms of trust, while not completely irrelevant (more on this below), ignores much of the complexity of the relations between science and society. To take only one example, in 2011, at a time when 87% of the French respondents expressed their faith, a majority of them (52%) also showed mixed feelings when asked if, generally speaking, they thought that “science does more good than harm, more harm than good, or roughly as much good as harm”. The following graph shows the evolution of the responses to that same question between 1972 and 2011.

This seemingly simple question aptly reflects the ambivalence that can be found in most European opinion surveys, concerning the applications of science rather than science itself. Artificial intelligence (AI) and big data are a telling example. These technical-instrumental advances allow researchers to analyse and disseminate an ever-growing mass of genomic, clinical and epidemiological information that is made publicly available via online platforms, in the same way as the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data.4 This generalised pooling of data – open science – is seen as the virtuous side of globalisation. On the other hand, these breakthroughs also prove useful for government authorities that are struggling to contain the spread of the virus as rapidly as possible, and are sometimes more concerned with controlling the population than respecting privacy and individual freedom.

Which of these two uses of AI and big data will gain the most public attention? With what type of variations from country to country? In this situation it is vital to conduct large-scale surveys in order to establish a world map of the public image of the sciences, and more generally of scientific culture. A dedicated international project, led by Michel Claessens (Free University of Brussels) with Martin Bauer (London School of Economics) and Ren Fujun (National Academy of Innovation Strategy, China), has been in development since 2019.5

The scientific community under pressure

The second reason has to do with the pressure exerted upon the scientific community. Research progresses at the confluence of multiple temporal factors, but during a plight, the pace is constantly accelerating. In its issue of 17 March, 2020, The Scientist reported that coronavirus experts were literally “submerged” by the wave of requests to review manuscripts. Putting such pressure on the peer review process is not without risk for scientific integrity – nor is it truly unprecedented, since the problem arises during every public health crisis.

What is new lies mainly in the changes that have taken place since the early 2010s in the way research results are collectively evaluated. The development of open and post-publication peer review platforms like F1000, Publons and PubPeer has led to many withdrawals, even among the most prestigious publications. PubPeer, for example, triggered an uproar in the field of RNA interference,6 and the current controversy surrounding hydroxychloroquine is no less interesting.

Like the public, science journalists did not know all of the reasons why reviewers, including the editors of the International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, accepted a manuscript submitted on 16 March, for publication the following day, entitled “Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial”. Nor did they know why one of the paper’s co-authors withdrew soon thereafter from one of the scientific boards appointed by the French government to “enlighten public decision-making in the management of the sanitary crisis linked to the coronavirus”. They could, however, read the exchanges among peers on the online platforms and observe the ever-increasing number of doubts and questions that had remained unanswered.7

At this point, the journalists’ next step was to relay those misgivings, sharing them with a wider audience. In an article in Le Monde on March 24, Hervé Morin, Sandrine Cabut and Nathaniel Herzberg reported that the publication of the paper by a Marseille-based team raised a series of questions on PubPeer, a website devoted to pointing out methodological weaknesses in scientific production. Contacted by Le Monde to clarify these various points, one of the co-authors did not respond. Clearly, open and post-publication peer review platforms, along with scientific information blogs8 and other such websites, now form an ecosystem of watchdogs that makes the institutional management of the scientific community’s public image more complex than ever before.

The experts’ delicate position

Lastly, the third reason lies in the fact that in times of sanitary crises, scientists often turn into experts mandated by the public authorities to estimate the risks and formulate recommendations. All sociologists are aware of this, especially those who investigate the difficulties of implementing compulsory vaccination policies:9 in any assessment of risks concerning health and the environment, the expression of trust depends on the perceived distance between scientists and political leaders.

According to the above-mentioned survey from 2011, while 87% of the respondents stated that they had faith in science in general, only 48% trusted “governmental agencies” in charge of overseeing health and environmental hazards. Today, France’s editorial writers are forever emphasising the political weight granted by the government to its two scientific boards, one chaired by Jean-François Delfraissy and the other by Françoise Barré-Sinoussi. What is less obvious is the complex position of these experts who, conscious of their high public profile, must participate in political decisions while remaining far removed from politics.

In his excellent book The Honest Broker (Cambridge University Press, 2007), author Roger Pielke makes the distinction between four types of expert, representing four ways of perceiving the relation between science and politics: the “Pure Scientist” explains the state of knowledge without considering its political applications; the “Science Arbiter” gives factual answers to the authorities’ questions without revealing his own preferences; the “Issue Advocate” upholds a specific line of thought and tries to influence governmental choices accordingly; and lastly, the “Honest Broker” tries to present a full range of alternatives so that the political leaders can make choices based on their preferences and values. No doubt the capacity of scientific board members to choose between these different models will help determine whether the impact of the coronavirus crisis on the image of scientific expertise is sustained.

The author is solely responsible for the points of view, opinions and analyses expressed in this article, which do not in any way constitute a statement of the CNRS’s position.

- 1. See Interview with D. Wolton, CNRS News, March 25, 2020.

- 2. “‘Fake news’ and misinformation around the SARS-CoV2 coronavirus”, Inserm Press Office.

- 3. “‘Fake news’ and misinformation around the SARS-CoV2 coronavirus”, Inserm Press Office.

- 4. https://www.gisaid.org/

- 5. Site of the WISE project.

- 6. Michel Dubois and Catherine Guaspare, “Is someone out to get me?” (Molecular biology tested by PostPublication Peer Review), Zilsel, October 2019, p. 164-192.

- 7. https://pubpeer.com/publications/B4044A446F35DF81789F6F20F8E0EE

- 8. Hervé Maisonneuve's blog is one example in France.

- 9. See Jeremy K. Ward, Patrick Peretti-Watel, Aurélie Bocquier, Valérie Seror, Pierre Verger, “Vaccine hesitancy and coercion: all eyes on France”, Nature Immunology, 2019.