You are here

The Framework of Notre-Dame: Putting an End to Stereotypes

Once the emotion sparked by the burning of Notre-Dame subsided, a number of contradictory remarks began to circulate regarding the destroyed framework, namely that the wood had to be dried for a number of years before being used, and that entire forests had to be cut down in order to build and rebuild it. It is therefore worthwhile to provide an overview of our knowledge of the framework and wood used for Notre-Dame during the 13th century, as well as the possibilities for reconstructing a wooden framework based on the techniques used during the Middle Ages.

Studies of the Gothic framework

Quite fortunately, precise architectural surveys of medieval structures were produced in 2015 by the architects Rémi Fromont and Cédric Trentesaux, a short synthesis of which was published in 2016 by the journal Monumental,1 along with those conducted in 1915 by the architect Henri Deneux, and a DEA pre-doctoral thesis on the dendrochronologyFermerTimber dating method from tree rings (rings). completed in 1995 by V. Chevrier.2 What's more, a scan of the framework was completed in 2014 by the company Art Graphique and Patrimoine (150 scans).

A complete and accurate survey of the framework had indeed been completed. The disappearance of this framework nevertheless represents a major scientific loss with respect to our knowledge of wooden constructions from the 13th century, for its archaeological, traceological, and dendrological analysis had yet to be done. Numerous complementary studies deserved to be conducted, in order to understand the functioning of structures, procedures for construction and hoisting, types of assemblies, phases of construction and repair, as well as the organization of the construction site and its advancement.

The dendrochronological dating conducted in 1995 was inaccurate, and had to be refined in order to date the site's different campaigns and restorations down to the precision of a year. The dendrological study also deserved to be completed, in order to determine the origin of the wood and the profile of the felled oaks (morphology, age, growth...), and thereby the state of the forests used during the 13th century.

This study remains to be done, based on existing documents and charred remains. This loss is all the greater because it's not just one Gothic framework that was destroyed, but three: the one constructed over the choir around 1220, the one belonging to the first framework from the 1160s, whose wood was reused, and the one over the nave (1230s?), which was much more sophisticated than that of the choir.

Those belonging to the two arms of the transept, the spire, and the bays of the central nave near the spire dated from the works carried out by Lassus and Viollet-le-Duc in the mid-19th century.

Lumber and forest use during the 13th century

The documents available to us and the studies of other major frameworks from the thirteenth century answer some questions. The wood used in medieval frameworks was never dried for years before being used, but was hewn while still green, and set in place shortly after being felled. They were oaks from the closest forests belonging, in all likelihood, to the bishopric. Each beam is an oak squared off (trunk cut into a rectangular section) with axes, conserving the heart of the wood at the centre of the piece. Saws were not used during the 13th century to cut beams. Felled oaks precisely matched the cuttings sought by carpenters, and their squaring off was done as close to the trunk's surface as possible, with little loss of wood. Wood hewn in this way retained its shape, unlike sawn wood. The trunk's natural curves were thus conserved during cutting, which was in no way a handicap for 13th-century carpenters.

Young oaks, thin and slender

It is estimated that the construction of the Gothic framework of Notre-Dame's nave, choir, and transept used approximately 1,000 oaks. Approximately 97% of them were hewn from boles measuring 25-30 centimetres in diameter, with a maximum length of 12 metres. The remaining 3% were boles measuring 50 centimetres in diameter, with a maximum length of 15 metres, and were used as centrepieces (tie beams). These proportions were similar to those measured in the 13th-century frameworks of Lisieux, Rouen, Bourges, and Bayeux Cathedrals. Aside from their small diameter, the majority of these oaks were young, with an average age of 60 years, and underwent growth spurts according to the dendrochronological studies conducted on most 13th-century frameworks in the Paris Basin. We are therefore far from the idealized image of enormous, centuries-old oaks with thick trunks.

These young trees, which were thin and slender, came from mature forests with maximal density, where the great competition between oaks forced them to grow very quickly toward the light at the top rather than in thickness. These medieval mature forests, which were managed according to a specific silviculture—based on regeneration through clear-cutting and cutting back, and with no thinning out in order to preserve the hyperdensity of the population—massively and rapidly produced oaks perfectly adapted to wood-based construction and axe-based cutting techniques.

For these reasons, the forest surfaces used by these major construction sites represented no more than a few hectares, just 3 hectares for the 1,200 oaks in the framework for Bourges Cathedral.3 We are once again far from the legendary clearing of forests needed to construct a Gothic cathedral...

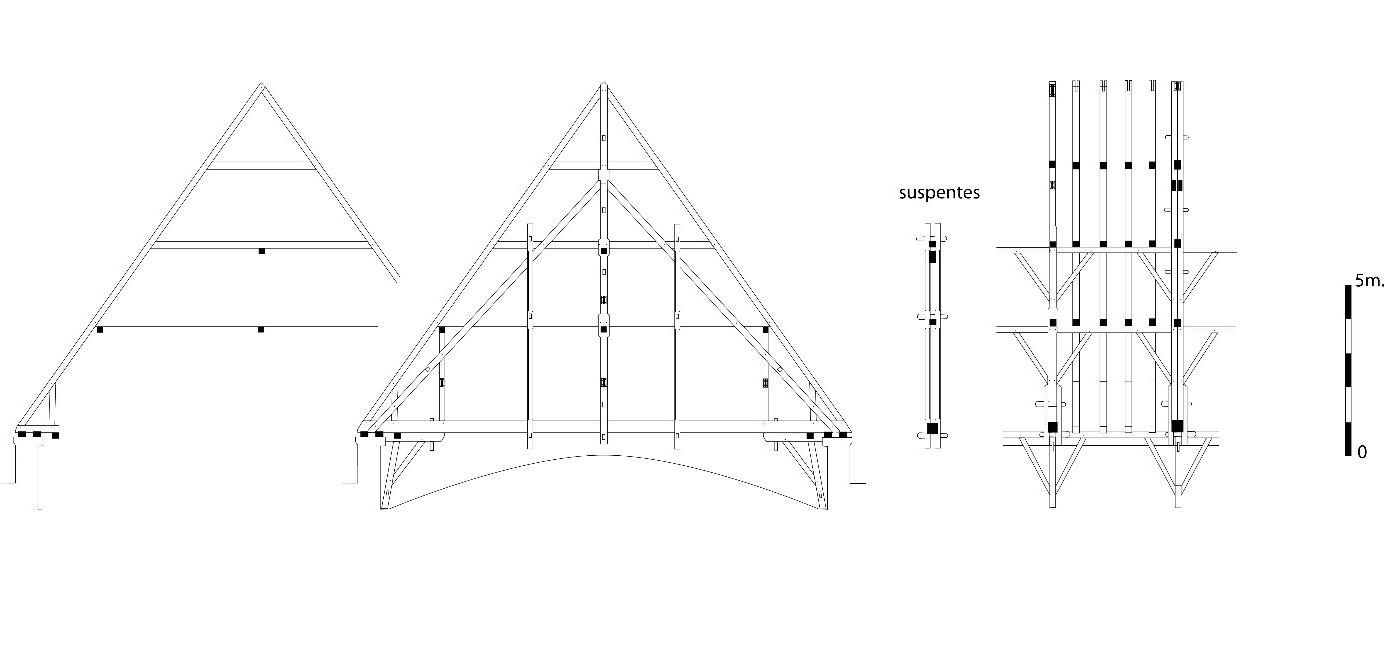

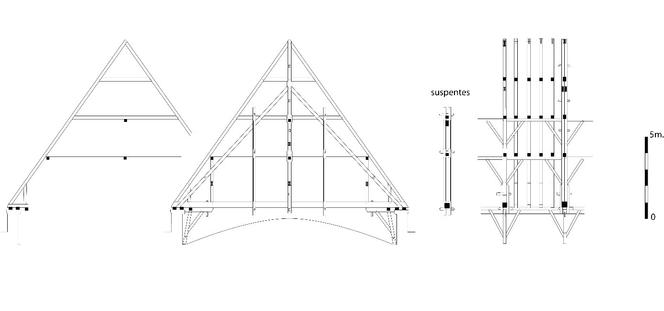

The framework's structure

In the early 13th century, master carpenters faced unprecedented difficulties arising from the huge size of Gothic cathedrals, and especially from the difficulty in adapting the framework to thin walls pierced with large stained-glass windows, and the powerful thrust of winds on the increasingly high and steep roofs. This challenge was all the more difficult as the period's "trussed rafter bracing" frameworks generated powerful lateral thrust on the walls, and the wood used was thin and therefore flexible.

The master carpenter of Notre-Dame met this challenge with brilliance by designing a complex but balanced structure, stable itself as well as for the walls, using numerous measures to tighten the trusses, reinforce the beams, double the triangulation, in addition to systems of struts to relieve heavy wood, short spans to limit the lateral thrust of the trusses, the transfer of loads from secondary to primary trusses using lateral and axial ribs, a steep pitch, and other techniques for ensuring that the structure retains its shape and distributes loads evenly along the walls. He did not hesitate to load the structure with all of the systems that were needed, with hundreds of secondary pieces, subsequently making it much denser than most frameworks of its time, and earning it its nickname: the "forest."

The master builder perfectly synthesized all of the experiments carried out on the major building sites of this period. He was most certainly one of the boldest and most important master carpenters of his time. Notre-Dame’s 13th-century framework was among the largest masterpieces of French Gothic carpentry, due to its technical complexity and extraordinary state of conservation.

We are familiar with the time needed to complete a trussed rafter bracing framework, which was not as considerable as we might imagine. The construction of the 13th-century framework of Bourges Cathedral took only nineteen months for a team of 15-20 carpenters, from the squaring off of the 925 oaks to the hoisting of the trusses.

What about the remains?

Presently, a collective of researchers including framework specialists, anthracologistsFermerWho analyzes the charcoal and determines the tree species from which it comes., dendrologist, ecologists, climatologists, and biogeochemists is proceeding with a research project aiming to collect and study the burned remains of the framework, whenever they become accessible. It is already clear in everyone's minds, including the heritage administration, architects, elected representatives, and researchers, that the remains of the framework should be preserved for conservation purposes after they have been studied.

What wood should be used to rebuild?

With regard to the lumber that is required, as stated earlier 97% of the wood used for Notre-Dame during the 13th century was small in diameter (25-30 cm), with a maximum length of 12 metres, which corresponds to "small" oaks that are easy to find. The cutting of 1,000 oaks is not an obstacle, as the country has the largest forest in Europe, with 17 million hectares (ha) of forests, of which 6 million are oak groves, with steady growth in recent years. The selection would certainly not take place through clear cutting, as has often been said, because today's mature forests are different from those of the 13th century (of which only 3 ha were sufficient), and because these "small" oaks are dispersed among current populations. They would therefore be cut by selective felling, with targeted individual cuttings within mature forests, thereby limiting the ecological impact on forest ecosystems. Let us recall that the production of the boat L'Hermione required 2,000 oaks by selective felling, or double that of Notre-Dame, without it presenting any environmental concern.

The reconstruction of an oak framework would promote the French forest sector, which is experiencing difficulty today due to the under-exploitation of mature forests, and the massive exporting of raw wood, notably to China. Today the use of a biosourced material, prepared according to traditional techniques, is an important signal of a reasoned and ecological management of our natural resources, and of a green economy oriented toward artisanal know-how.

What framework should be reconstructed?

In the past, the reconstructions of burned cathedral frameworks were often identical to the 13th-century original out of respect for the monument, as with Meaux Cathedral in 1498, Rouen Cathedral in 1529 and 1683, Lisieux Cathedral in 1559, or with numerous historic monuments during the 19th century. Of course, for economic reasons, there were just as many frameworks that were rebuilt without taking the original into account.

The concrete framework built in 1919 for Reims Cathedral, or the metallic one built in 1836 for Chartres Cathedral, were produced according to this principle, out of a shortage of quality lumber due to a lack of nearby mature forests, and not from an evident desire for technological innovation. The extraordinary donations collected for Notre-Dame, in addition to the potential of today’s forests, should not present obstacles for decision makers with regard to these economic choices. Furthermore, the use of contemporary materials ensures neither the very long-term longevity of the structures, as oak has proven over eight centuries, nor the transmission of the traditional know-how of cathedral “builders.”

For that matter, innovating and leaving the mark of our times on Notre-Dame is not as legitimate as it once was, due to the building’s classification, which makes any restoration subject to the Venice Charter. Article 9 (link is external)of this charter stipulates that a destroyed section must be faithfully reproduced with respect to the earlier substance, as long as this is documented by precise surveys. We have a complete and precise survey, even though the later additions must still be defined in order to faithfully reproduce its original appearance. We are also familiar with the spire's structure thanks to a scale model belonging to the compagnons charpentiers (French carpenter's guild). The reproduction of the Gothic "forest" is therefore possible, and is indeed required by the regulations of the Monuments historiques.

Aside from the material and form, the debate should especially consider the techniques to be used.

What techniques should be used today?

While the forms of frameworks have ceaselessly evolved over the centuries, the "traditional" techniques for manual cutting using axes did not change from the Middle Ages to the early 20th century. Contrary to widespread notions, these techniques are almost entirely unused today in major carpentry companies, as they require modernisation, along with improvements to digital machining tools and electrical machine tools. Neither the companies of the Monuments historiques nor the compagnons charpentiers square off wood using axes, instead supplying themselves directly from the sawmill. The survival of this know-how is therefore an issue, as it is disappearing in similar fashion in all European countries. Only a few rare artisanal companies still cut using the broadaxe, seeking to preserve the transmission of a centuries-old know-how, and the very essence of their trade through control over the entire operational chain from tree selection in forests to manual cutting and installation. These traditional techniques are nevertheless economically viable and profitable for these small companies.

There is a distinct difference between a work produced traditionally and one using industrial techniques, as wood squared off by axe is more solid and stable than sawn wood: it does not warp while drying, curved wood can be used, lumber is less costly because it is adapted to sectioning, waste is minimal, the work is more attractive through its respect of the trunk's natural form, and especially because carpenters once again find their love for the trade. This explains the success of traditional building sites such as Guédelon(link is external), or those of "charpentiers sans frontières(link is external)" (carpenters without borders), which bring together up to 60 professional carpenters from across the globe to restore a work. Recently, curators from the Monuments historiques and architects have called for wood to be worked according to traditional techniques, using the broadaxe for the restoration of old frameworks such as l'Aître Saint-Maclou in Rouen, although few companies are currently able to do so. They need to be trained to relearn this know-how, which is precisely what is being proposed by the government's bill for the restoration of Notre-Dame.

A similar building site-school in Notre-Dame square, with dozens of carpenters squaring off logs with axes, and cutting by hand according to the ancestral rules of the trade, would help companies re-establish a connection with this centuries-old know-how, in the spirit and continuity of cathedral building sites. Such a building site would surely prove spectacular and highly moving for the general public, as it would bear witness to our period's respect for a gestural and technical heritage that deserves being preserved in France as an element of our cultural identity, and even more so on one of the nation's most cherished monuments.

The true technological challenge represented by the reconstruction of Notre-Dame’s framework is not to build a high-tech structure using contemporary materials, which we know how to do very well for train stations and airports, but instead to produce an oak framework that is respectful toward traditional know-how.

This choice would be strikingly modern, as it would allow a trade to reappropriate techniques that are respectful of the monument, humans, and the wood, by virtue of using a biosourced material selected so as to promote our forest resources in accordance with an environmental ethic, and working by hand with an almost zero carbon footprint, based on concerns that are nevertheless firmly anchored in the 21st century.

The analysis, views and opinions expressed in this section are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policies of the CNRS.

___________

Further Reading

"Les forêts et le bois d’œuvre au Moyen Âge dans le Bassin parisien," F. Épaud, in La Forêt au Moyen Âge, Les Belles Lettres, forthcoming.

De la charpente romane à la charpente gothique en Normandie, F. Épaud, Publications du Centre de recherches archéologiques et historiques médiévales, 2007.

- 1. "Le relevé des charpentes médiévales de la cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris: approche pour une nouvelle lecture," R. Fromont, C. Trentesaux, Monumental, bi-annual1, Éditions du Patrimoine, 2016.

- 2. "La charpente de la cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris à travers la dendrochronologie," Chevrier V., DEA pre-doctoral thesis, Université de Paris-Sorbonne, Paris IV, 1995.

- 3. La charpente de la cathédrale de Bourges. De la forêt au chantier, F.Épaud, Coll. "Perspectives historiques," Presses universitaires François-Rabelais, 2017.