You are here

Who Was the First Artist?

What if, long before Leonardo da Vinci or Michelangelo, the Neanderthals were humanity’s first artists? At any rate, this is the hypothesis raised by new dating of Spanish rock paintings published in February 2018 in the journal Science,indicating that the hands and animals depicted on the walls of three caves date back 65,000 years. This would mean that they were painted 25,000 years before the arrival of the first Homo sapiens in the Iberian peninsula. The estimated ages are based on uranium-thorium datingFermerRadiometric dating method to measure the age of certain animal (eg coral) or sedimentary formations of the layer of calcite that coats them. of the calcite layer that coats the frescoes. Could these be the work of Neanderthals? A certain amount of additional data supports this view. For example, traces of pigments in a shell have been dated to 115,000 years ago, while drawings of cats and handprints in the Grotte des Merveilles, Rocamadour (southwestern France) are believed to be between 50,000 and 70,000 years old. In light of this evidence, it is not difficult to imagine that the Neanderthals were endowed with artistic ability.

The interpretation of this research, however, is purely speculative at present. Firstly, the estimated ages will have to be confirmed by other dating methods, especially since no Neanderthal bones were found in these caves.

And secondly, the Neanderthals’ artistic and symbolic aims are totally unkown. “In concrete terms, we know little about their social organisation,” explains Claudine Cohen,1 a philosopher and historian of science who specialises in prehistoric representations. She adds: “To talk about Neanderthal artists isn’t quite right, for while there is symbolic expression, there is no evidence that there were specialised artists in their societies.”

Cohen’s qualified assessment is shared by Camille Bourdier, lecturer in prehistoric art at the TRACES laboratory,2 in Toulouse (southwestern France): “It remains to be established whether Neanderthals actually produced these rock paintings. The first results are still the subject of debate within the scientific community, both as regards methodology and the interpretation of the findings.”

Long regarded as our “primitive” cousins, Neanderthals are now being rehabilitated. Capable of carrying out burials, collecting objects and making sophisticated tools, as well as having the gift of language, “Neanderthals certainly weren’t that different from us,” Cohen believes. “Whether they had art or not is probably the last point we need to clarify,” points out Audrey Rieber, a researcher at the IHRIM,3 who believes that “it won’t be long before we’ll be talking about Neanderthal art”.

The social role of the artist

However, for Bourdier, the question is not whether Neanderthals, like us, were able to create works of art, but rather whether their social organisation required paintings on rock walls. Indeed, “like any other image, these are messages that convey information. They therefore fulfil a social role, whether its significance is spiritual, historical, educational or anecdotal.”

In fact, what determines artists’ status is the position hold in society. “The term ‘artist’ refers to a socio-professional category of specialists whose social identity stems from the production of graphic or visual art,” Bourdier adds. However, for both the Neanderthals and Homo sapiens of the Upper Palaeolithic (35,000 to 10,000 years ago), there is almost no trace of these social identities.

In many ways, the debate about the status of Neanderthals as artists echoes that around the recognition of rock art in the early twentieth century. Although the Altamira cave, the crowning glory of Spanish cave art, was discovered in 1875, its authenticity was not confirmed until 1902. “There is a significant time lag between the discovery of these paintings and their inclusion in the history of art. The scientific community recognised their obvious beauty, but not the fact that Palaeolithic humans produced them,” Rieber points out.

Confronted with a complex, magnificent work of art, scientists and archaeologists initially thought it was a fake. At that time, the prevailing view of prehistoric humans ruled out any possibility that they had artistic abilities, reducing them to the inherent capacity of any primitive species to reproduce the shape of a few animals by simple imitation.

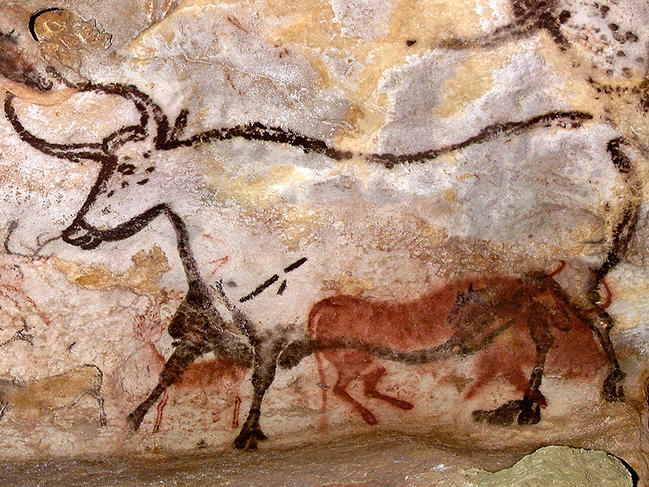

“Modern artists, such as Picasso, Vlaminck and Miró, were certainly among the first to have been fascinated by the modernity of rock art, well before art historians,” says Cohen. On a visit to the Lascaux cave in the Dordogne region (southwestern France), Picasso reportedly exclaimed, “We haven’t invented anything!”

However, although Ernst Gombrich (1909-2001) opened his famous 1950 work, The Story of Art with prehistoric art, he excluded it from “our” history, which he considered to have begun with the ancient Egyptians. “I think that, at the time, art theorists were uncomfortable with the notion of a Palaeolithic artist, because this called into question the status of the artist, which until then had been based on Renaissance art, understood as the beginning of modernity,” Rieber explains.

Stylised art

The reason why the process of recognising prehistoric art is so slow is that it is still difficult to know what motivated prehistoric artists. “We initially thought that they were producing art for art’s sake,” Cohen points out.

It is safe to say that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens alike could be driven by certain aesthetic principles. And, like modern artists, they used engraving and sculpting tools, brushes, stencils and pigments. In addition, the Palaeolithic art discovered until now is stylised: “Although depictions of animals are always very realistic, representations of men and women are rudimentary and stylistic, with an emphasis on the genitals and the central parts of the body, while the face is usually absent or concealed,” the researcher emphasises.

Archaeologist and ethnologist André Leroi-Gourhan has shown that rock art was very structured, with compositions that combine animal and human figures and symbols. For example, women are consistently associated with bison, and men with horses.

It is therefore impossible to consider these paintings as isolated, archaic imitations, when in fact they are genuine, well-constructed and thought-out works of art. “When you discover Lascaux, you can no longer deny that these are works created by artists,” Cohen approves.

If we regard our ancestors as artists, does that mean art was a profession in those days? “In the Upper Palaeolithic, we can certainly say that there was division of labour. Such elaborate productions suggest that in these societies, the ability to depict the world was entrusted to certain people,” Cohen believes.

The Lascaux and Chauvet paintings were undoubtedly not the work of amateurs but of talented people whose skills had been handed down. “Cultural exchanges between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals are also the subject of debate: they both used the same pigments, but who borrowed from whom? Was knowledge passed on?” Cohen wonders.

Finally, is it right to say that prehistoric humans had style? One thing is certain: Palaeolithic art is the focus of significant research, whose primary objective is to “define and distinguish iconographic traditions in time and space,” Bourdier explains.

In other words, it is a matter of identifying historical connections or ruptures in rock art. Stylistic analysis then concentrates on the artists themselves, to determine their specific touch. How many artists participated in the work? “Were there several of them, and were they always the same? If so, this once again raises questions not only about how specialised activities were, but also about the mobility of these people and, more generally, of human groups,” Bourdier concludes.

Viewing the past through the prism of the present

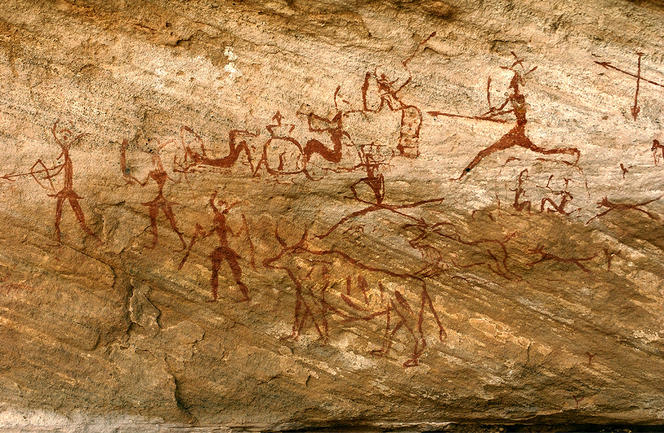

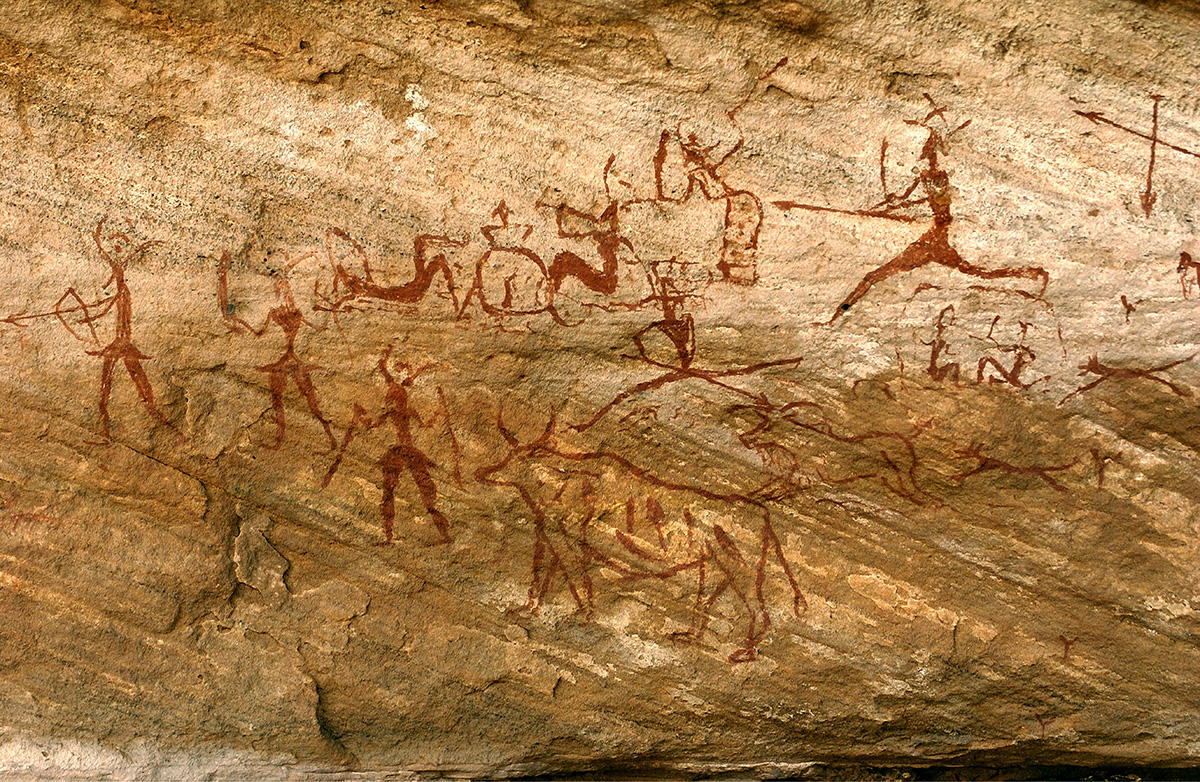

Analysing these paintings also provides information about social organisation and everyday life at the time. As social relations in the Neolithic became more complex, sedentary life, farming and animal husbandry began to develop. “New themes such as hunting or honey harvesting start to appear in the frescoes. In the western Mediterranean, common, repeated themes and symbols are used: stylised human forms are the most frequently depicted, but animals are also represented, especially deer and goats, as well as sun-like patterns and zigzags," explains Esther López-Montalvo, an archaeologist and specialist in Neolithic art at the TRACES laboratory.

Levantine Neolithic art, on the other hand, marked a radical break with earlier graphic traditions due to its strong naturalistic and narrative character. Hunting and virility were exalted, while “artists depicted important social activities,” according to López-Montalvo. Was this a form of communication, or did it have an aesthetic or ritual purpose? “It seems likely that it was a way of asserting a social and symbolic identity,” she explains.

“In Levantine art, women are often depicted in isolation, and they take no part in male settings,” she adds. Neolithic art reveals that there was already a gender imbalance in these societies. So were the artists men? The violence expressed in these pictures, with scenes of war and executions, reveals a complex social organisation and political conflicts. “This art can almost be treated as a historical source. It reflects Neolithic society very closely,” she believes.

In the absence of material evidence, however, interpreting prehistoric art is sometimes subject to retrospective illusions, often based on our modern conception of art.

“For example, in the early 20th century, cave painting was considered a religious art, partly because those who studied it were priests,” Cohen recalls, referring to the Abbé Breuil, a Catholic priest and specialist in rock art nicknamed the “pope of prehistory,” who played a part in the discovery of decorated caves in the Dordogne. “We can see the extent to which interpretations reflect the present,” she says.

Not masters of their works

Although granting Neanderthals the status of artists might appear somewhat premature, it has the advantage of questioning our relationship to art and artists. How can a work of art be recognised as such when nothing is known about the artist, and when its meaning is bound to remain speculative? To what extent can this work be considered as art, the result of creative talent, and not as craftsmanship?

In antiquity, manual labour was not as highly regarded as intellectual endeavour. The ancient Greek Muses did not encompass painting or sculpture. In Aristotle’s view, the liberal arts practitioners of the time were outstanding individuals who rose above their condition through knowledge and thought, rather than through the visual arts.

“In the Middle Ages, between the fifth and fifteenth centuries, it is difficult to find one single status for artists,” says Rosa Maria Dessì, a mediaevalist at the CEPAM4 laboratory, in Nice (southeastern France). At the time, the term “artist” referred to students and teachers in the Faculty of Liberal Arts. Someone who worked with their hands was known as an “artifex” or craftsman—a function defined by the clerics.

Inspired by God, they had but one aim, that of reproducing the acts of Creation. The stained glass windows and paintings located high up in cathedrals and often not even visible, for example, “were not intended to be understood by humans, but to be seen by God,” Dessì points out.

The rapid growth of cities in the twelfth century probably heralded the real beginnings of the craft industry, with the emergence of guilds, which provided artists with regulations, solidarity and financial support. From then on, painters and sculptors ranked highest in the hierarchy of trades and were becoming aware of the value of their skills. However, these changes were slow: “In fourteenth-century Florence, before painters formed their own guild, they were included in that of doctors and apothecaries, since they all used plants and pigments,” notes Dessì.

Although artists began to have a role in society, they were not yet the masters of their own works, which were collective rather than individual endeavours. Creation was an integral part of a well-defined hierarchy, in which workshops were known by the name of the master. “In the Middle Ages, it was difficult to attribute a work to a single artist, because it was often anonymous,” Dessì explains. At that time, works could be altered, or even obliterated. To whitewash or rework a Giotto painting conveying a political message would be unthinkable today.

“In fact, talking of artists in pre-Renaissance times is an anachronism,” says Rieber. The figure of the artist as we understand it today—that of the creative genius—emerged during the Renaissance, which gave rise to so many masterpieces of painting and sculpture. Yet this was limited to a handful of famous names. In 1571, a few artists from Florence became independent of the guilds and started working in academies, which had hitherto been reserved for the liberal arts.

The Renaissance thus heralded the emergence of classical artists, who were “liberal professionals, carrying out their work within an academic context. It was not until the nineteenth century that the figure of the romantic artist, driven by vocation and deep inspiration, began to appear,” explains Nathalie Heinich, a sociologist specialised in artistic professions and cultural practices at the CRAL.5

After the French Revolution, creative artists took the place of the deposed aristocrats. They “became a new elite, although they were sidelined and stripped as far as possible of power and money,” says Heinich.

From the second half of the nineteenth century onwards, the image of the modern artist gradually took hold, first in the eyes of specialists and then among the general public: “Art was increasingly understood as a means of expressing the artist's inner self, rather than as an ideal or realistic depiction of the world. The second half of the twentieth century then saw the gradual emergence of the figure of the contemporary artist, who was supposed to be transgressive, often with a touch of irony and off-beat humour, radically departing from the still romantic image of the modern artist dedicated to their vocation,” Heinich explains. As an example of this, she points to Marcel Duchamp, who was one of the first to reject the notion of painting as a career, as academic professionalism, or as the vocation of the inspired artist.

Art and progress

“After Altamira, all is decadence,” Picasso is reported to have said after visiting the famous cave. Recognising that there were artists in Neanderthal societies challenges the notion of progress in art. Does art follow a timeline that tends towards more beauty, perfection and technique? “From the artist's point of view, this chronology makes no sense, even if it is the way in which art is usually presented,” says Rieber, who rejects the idea that “art today is at its peak.” The recent findings about Neanderthals could have the merit of reviving the debate.

All this raises an intractable question: what is art? “I’d be very hard put to find an answer!” Rieber laughs. Cohen goes even further: “Shouldn’t we consider that, ultimately, the first artists were those who carved flint to make beautiful almond-shaped hand axes, thus clearly displaying a sense of aesthetics?,” she wonders. In which case, art may have emerged two million years ago—long, long before the Neanderthals…

- 1. Director of studies at the EPHE and at the EHESS School of Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences, she is a member of the Biogéosciences (CNRS / EPHE / Université de Bourgogne) and CRAL (CNRS / EHESS) laboratories.

- 2. CNRS / Université Toulouse Jean-Jaurès / Ministère de la Culture.

- 3. Institut d’Histoire des Représentations et des Idées dans les Modernités (CNRS / Université Jean-Monnet / ENS de Lyon / Université Louis Lumière Lyon-2 /Université Jean-Moulin Lyon-3 / Université Clermont Auvergne).

- 4. Cultures et Environnements, Préhistoire, Antiquité, Moyen Âge (CNRS / Université de Nice Sophia Antipolis.

- 5. Centre de Recherches sur les Arts et le Langage (CNRS /EHESS).

Explore more

Author

Léa Galanopoulo has a biology degree and is currently studying scientific journalism at Paris-Diderot university.