You are here

A Medieval Treasure Discovered in Cluny

In archaeology, a discovery can be a matter of a few centimeters. Narrowly escaping demolition in the 18th century, and later the teeth of an excavator, a fabulous treasure was found at the Abbey of Cluny in Burgundy (northeastern France) last September. Two months on, the researchers have published an initial inventory: more than 2,200 silver coins, 21 gold dinars, a gold signet ring1 with a Roman intaglio2, a folded piece of gold leaf, and a small gold object.

Unearthing old structures

With so many coins, all minted in the first half of the 12th century, this cache constitutes an exceedingly rare find for medieval Europe. Anne Baud, an academic at the Université Lumière Lyon 2, and CNRS engineer Anne Flammin, both of whom work at the ARAR,3 were investigating something completely different when they began this excavation campaign in 2015. Even though Cluny was the center of the most extensive network of monasteries ever formed in the Middle Ages, none of the original complex survives, except for one wing of the transept. The archaeologists’ goal was therefore to find traces of the old buildings.

“We were focusing on the infirmary, an important part of the abbey that functioned like a small monastery within a larger one," Flammin says. "It only housed sick or elderly monks, who were subject to different rules—particularly in terms of diet, as they were allowed to eat red meat.” A study by the zooarchaeologist Benoit Clavel of AASPE4 on animal and fish bone fragments recovered from the site has allowed researchers to reconstruct the patients’ menu. Samples were taken from three excavations at the location of the infirmary’s main hall, as indicated by a map from 1700.

An accidental discovery

In order to reach the depth that they want to study as rapidly as possible, archaeologists often remove the upper layers of earth with an excavator.

It was during this operation that an MA student5 spotted a coin emerging from the stratigraphy.6 By chance, the shovel had only brushed past the treasure without damaging it. “We stopped everything and started digging by hand,” Flammin reports, in order to extract the hoard and document it before nightfall.

There was no question of leaving the treasure out in the open. It consisted of a cloth bag filled with more than 2,200 silver coins (deniers and oboles), most of them issued by the abbey in the first half of the 12th century. As the CNRS engineer points out, “Until now, the largest discoveries of Cluny deniers have represented at most a dozen coins each.”

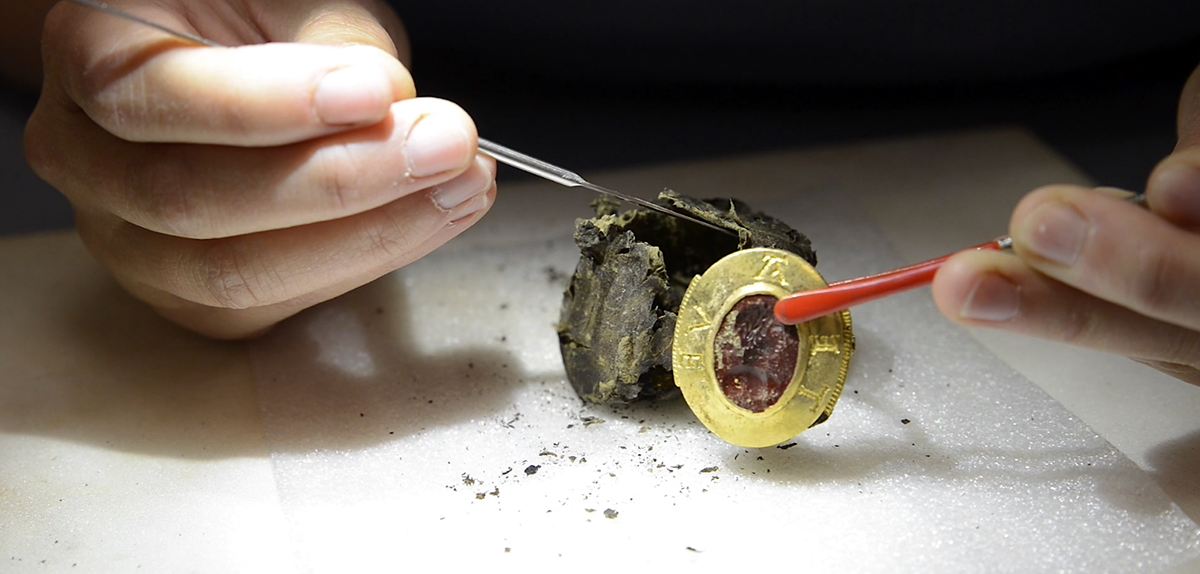

In the midst of these coins was a piece of tanned skin wrapped around the most prestigious items in the treasure: 21 Islamic gold dinars, a gold signet ring, a folded piece of gold leaf weighing 24 grams and a small gold object in the shape of a button. The dinars were minted between 1121 and 1131 in areas of Spain and Morocco controlled by the Berber Almoravid dynasty.

A mysterious treasure

How much was all that gold and silver worth at the time? Monetary values are often difficult to assess so many centuries later. Vincent Borrel, a PhD student working at the AOROC,7 studied the coins and estimates that “the treasure should have been enough to buy three to eight horses, the equivalent of the same number of cars today. It’s a considerable sum for an individual, yet it is by no means colossal on the scale of the abbey, for which it would have represented only a week’s supply of wine and grain for the monks.”

Indeed, the Order of Cluny had established priories throughout the Western medieval world. Via a complex network of transactions across Europe, many outposts forwarded their income to the main abbey, which had been authorized to mint its own currency since the 11th century.

While this explains the presence of the silver deniers, the gold coins are a much rarer find for that period. “No Christian gold currency was issued before Florence began minting its florins in 1252,” Borrel explains. The 21 gold coins in the cache came from the vast region of Islamic Andalusia, at a time when the Christians had reclaimed about half of Spain. The Order of Cluny had priories in the Christian areas, and one of them could have sent back the dinars following transactions with the Andalusians. The hypothesis of a direct donation from the Christian kings of Spain has also been proposed.

Despite the number and value of the coins, the most precious item in the treasure remains the signet ring. While the object itself was probably made in the 12th century, its inset, a small intaglio portrait of a god, dates back to the Roman Empire. Such a jewel would have been worth more than the rest of the trove combined. However, it is difficult to trace its history over the centuries and to determine whether the ring was a private possession or had an official function. In fact, many questions remain unanswered. Who hid this treasure, and why? “Perhaps a member of the order wanted to bury his nest egg,” Flammin suggests. “The location of the discovery could also link it to the purser, the monk who handled the monastery’s food budget.”

One thing is certain: the researchers were very lucky. “The treasure was found just below the medieval ground level, in a site that had been razed to the ground in the 18th century to build the new abbey,” Flammin recounts. “The excavations show that the workers at the time stopped digging only 10 centimeters from the cache.”

- 1. A ring used to imprint a wax seal on documents and storage chests.

- 2. The hard inset of a signet ring used to make the imprint.

- 3. Archéologie et Archéométrie (CNRS / Université Lumière Lyon 2 / Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1).

- 4. Archéozoologie, Archéobotanique: Sociétés, Pratiques et Environnements (CNRS / MNHN).

- 5. The students participating in the excavations are from the archaeology-archaeological sciences master’s degree program at the Université Lumière Lyon 2.

- 6. The vertical cross-section of a site in which the successive archaeological layers are visible.

- 7. Archeology and Philology of East and West (CNRS / ENS Paris / EPHE).

Explore more

Author

A graduate from the School of Journalism in Lille, Martin Koppe has worked for a number of publications including Dossiers d’archéologie, Science et Vie Junior and La Recherche, as well the website Maxisciences.com. He also holds degrees in art history, archaeometry, and epistemology.