You are here

Unfolding 40 million years of Asian steppe history

From the northern foothills of the Tibetan plateau to southern Siberia, and from western Kazakhstan to eastern Mongolia lies one of the world’s largest ecosystems, the Central Asian steppe. As far as the eye can see, an ocean of grass harbours a rich biodiversity. Elk, gazelles, brown bears, leopards and Siberian tigers, among other remarkable species, have made it their home.

However, until now, there was something missing from this vast region: its natural history. The evolution of the steppe over geological time remained a mystery, since it had hardly ever been studied. A French-Dutch team has now set out to fill the gap, by publishing the first-ever chronology of the main climatic and environmental events that have affected the region over the past 40 million years. This segment of history shows the extent to which this grassland is fragile and vulnerable to climate change.

Using pollen as a time machine

To reconstruct the evolution of the steppe, the researchers made use of one of the best indicators of past ecosystems: pollen. Every grain has a specific shape and pattern, making it possible to identify the plant species or family that produced it. As a result, a record of successive floras is preserved in different geological strata.

In northwest China, the researchers found an exceptional location for the collection of pollen near the town of Xining, the capital of Qinghai province. “There we have a record that spans a period from 40 to 15 million years ago,” explains Guillaume Dupont-Nivet, a CNRS researcher at the Geosciences Rennes laboratory1 and at the University of Potsdam (Germany). “It’s a unique site that provided us with an overview of the history of the steppes.”

Collecting these microscopic grains is a particularly tricky job. “You have to be extremely careful not to contaminate samples with recent pollen,” the researcher explains. Under the microscope, it is indeed very difficult to distinguish a 30 million-year-old grain from one that has just been released from a nearby flower.

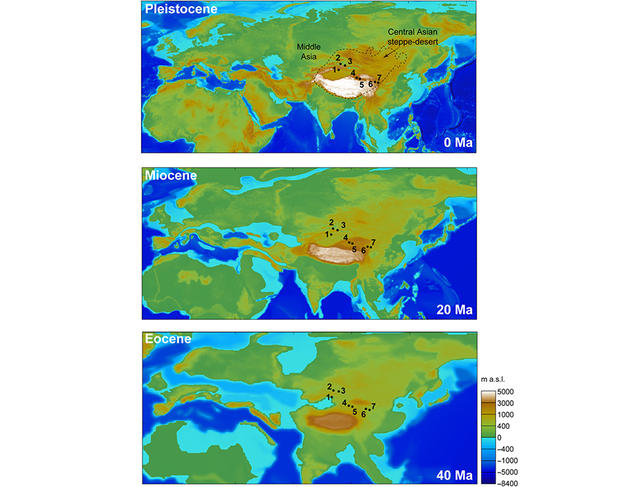

To reconstruct the history of the climate and environment of the region, the scientists also used other information. They relied on climate models, animal fossil records, and isotopic data that can help track variations in temperature and precipitation over millions of years. This enabled them to identify three major ecological phases in the steppes of Central Asia.

Successive climate upheavals

Some 40 million years ago, two families of shrubs, the Nitrariaceae and the Ephedraceae, were found everywhere in the region. These plants fostered the emergence of a remarkable fauna dominated by the ancestors of horses and rhinoceros, the Perissodactyla, or odd-toed ungulates.

But then the local climate started to change. The Himalayas and Tibet began to rise, pushed up by the collision of the Indian subcontinent with Eurasia, leading to a change in the monsoon regime. To the north of Tibet, rainfall started to decrease. At the same time, the Paratethys, the extensive sea that stretched from Mongolia to the Mediterranean, gradually dried up, causing the area to become increasingly arid.

However, the final blow that ushered in the end of these early steppes occurred 34 million years ago. A global crisis known as the Eocene-Oligocene Transition brought about a mass extinction of species in many regions around the world. It was largely caused by the formation of the Antarctic ice sheet, an event that rapidly cooled the planet, leading to a sharp drop in precipitation in Central Asia. The steppes turned into a desert as arid as the Sahara. Sand dunes covered the last refuges of life. In this hostile environment, the fauna mainly consisted of a few rodents and rabbits.

The desert persisted for millions of years. Then, in the middle of the Miocene, 17 to 14 million years ago, the climate became wetter again. As Dupont-Nivet admits, scientists don’t know what caused the change. Yet for whatever reason, there was a significant shift in conditions, which once again became more favourable to life. Steppes like those seen today, covered with grasses and shrubs, emerged. Large mammals, such as lions, aurochs and megaloceros (giant deer) encountered their ecological niche there, before being ruthlessly hunted down by a new invasive species that arrived 50,000 years ago: Homo sapiens.

The uncertain future of the steppes

This great ape may well turn out to be the cause of another environmental upheaval. Climate change models show that Central Asia is fast becoming one of the hottest and driest places on the planet. Researchers think that the steppes could turn into a highly arid desert again. Ecosystems are already visibly deteriorating, as shown by the expansion of the Gobi Desert, which has led the Chinese authorities to embark on a massive reforestation programme dubbed “the Great Green Wall”. “One possible scenario is that the advance of the desert will leave only scattered islands of fertility. Then, if the barren areas continue to expand, the fertile patches will in turn disappear,” the scientist predicts.

The problem is that this process could be irreversible. “What our work shows is that there is a threshold beyond which there is no turning back. Once a desert environment takes hold, it could last for millions of years. So, even if we managed to control levels of atmospheric CO2, returning to the previous situation would be impossible,” Dupont-Nivet warns. If this worst-case scenario were to come about, the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people would collapse in just a few decades.

- 1. CNRS / Université de Rennes 1.