You are here

The Music of Antiquity

What did the music of the ancients sound like? What role did it play in the life of Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Greek and Roman societies? These are among the questions addressed by an exhibition at the regional branch of the Louvre in Lens which is now heading to Madrid and Barcelona.1 “Music! Echoes of Antiquity” is a world first: no museum in France or anywhere in the world has ever hosted such a comprehensive event on ancient music. The list of institutions that have lent exhibits for the project—no fewer than 22, including the Louvre, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the British Museum—testifies to its scale and complexity. “In fact, the objects brought together on this occasion are largely unknown to music lovers,” explains the Egyptologist Sibylle Emerit,2 one of the eight curators involved. “They are never seen in musical instrument museums because it was decided, back in the 19th century, to place them in archaeological collections instead, alongside all other relics. Yet what a thrill it is to see a virtually intact Egyptian harp!”

The exceptionally dry climate of Egypt made it possible for researchers to recover nearly 600 remains of harps, flutes, sistra (metal rattles) and lyres, among others—quite a treasure trove considering the relative rarity of instruments from other early civilizations. However, while the oldest percussions are indeed Egyptian—castanet-like clappers dating from the Thinite period, ca. 3000 BC—the earliest string instruments are Mesopotamian: the famous Lyres of Ur, unearthed by the British archaeologist Leonard Woolley in the 1920s in present-day Iraq. “These lyres, dating from 2500 BC were found in the tombs of the royal family of Ur,” says Nele Ziegler, a historian specializing in Mesopotamia and co-curator of the exhibition.3 “We are extremely fortunate that these instruments, decorated with gold and precious stones, have survived, as the wood they were made of had completely decomposed. Yet Woolley's ingenious idea of making plaster casts of the empty spaces it had left enables us to admire them today.”

The oldest known chant

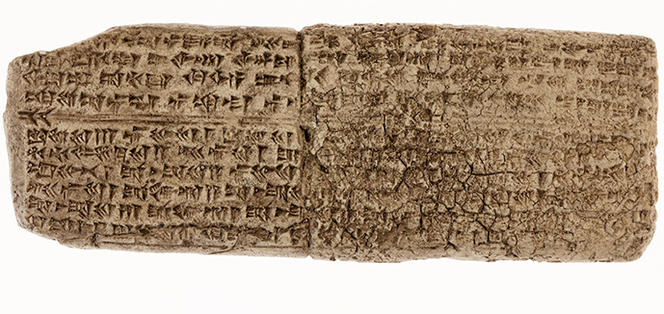

Although it has yielded relatively few such archaeological remains due to its unfavorable climate, Mesopotamia has proved a rich source of archives written on clay tablets, including some that document in minute detail the role of musicians in the region’s city-states. The most remarkable examples were found in the excavations of the Royal Palace of Mari, in modern-day Syria. “These 20,000 texts in cuneiform script represent 20 years of the life of the palace, before it was destroyed by Hammurabi of Babylon in 1759 BC,” Ziegler recounts. “Among these texts, the correspondence between the musicians and the king shows that they were very much a part of life in the city: they performed during religious ceremonies, or festivities to celebrate the king’s return from the battlefield. Most of the palace musicians were functionaries, who also assumed the duty of teaching music to the young women of the court.”

The inscriptions on the clay tablets also include the oldest song ever discovered: the Hymn of Ugarit, found in Syria and dated at 1400 BC. It is an ode to Nikkal, a goddess believed to favor human fertility. The text is accompanied by musical indications specifying the mode and intervals to be played. “Along with Greece, Mesopotamia is the only place where ancient musical notation has been found,” Ziegler adds. “Musical scores in the form of tablature have been identified from as far back as 1800 BC, as well as texts specifying the name of each string and the tuning of the instruments.” As for playing the melodies of ancient Mesopotamia today, “The best we can offer is an interpretation,” Ziegler admits. “We know the names of the notes and the intervals between them, but not what pitch each note corresponds to. Is it an E? An A?”

Among the scores that have survived from antiquity, two Delphic hymns found in 1893 on the wall of the Athenian Treasury are of particular interest. “These hymns to Apollo written in 128 BC were composed to accompany a ‘Pythaid,’ a pilgrimage to Delphi that the Athenians made on special occasions,” explains co-curator Sylvain Perrot, a specialist in ancient Greece.4 “They were performed by some 50 musicians, including about 40 choral singers, during the procession to the altar of Apollo before a ceremonial sacrifice.” The scores are highly complex, combining three different notations derived from the Greek alphabet: one for vocal music, one for instrumentals and another indicating the rhythm. “The notation is too complicated to be sight-read,” Perrot points out, “and was not intended to be used for performance. The most likely hypothesis is that the Greeks invented it to keep the melodies for posterity.”

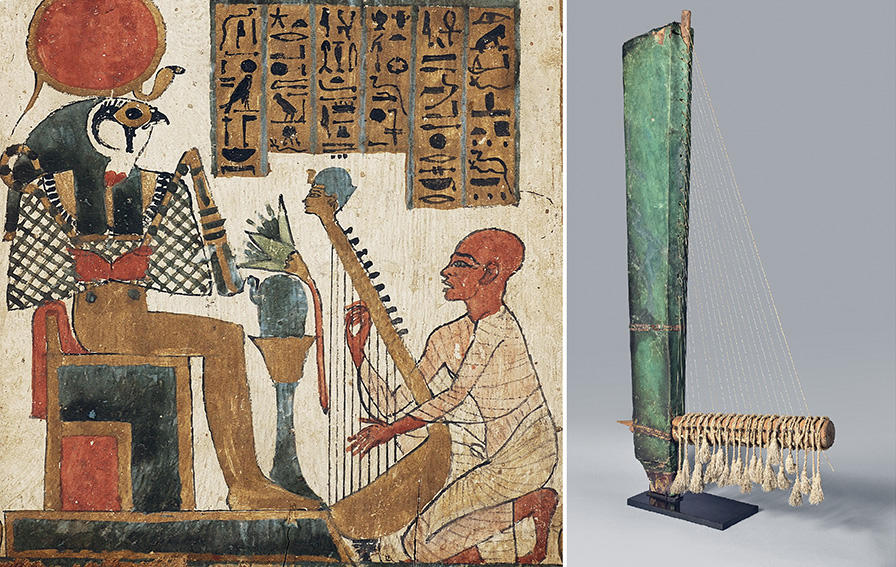

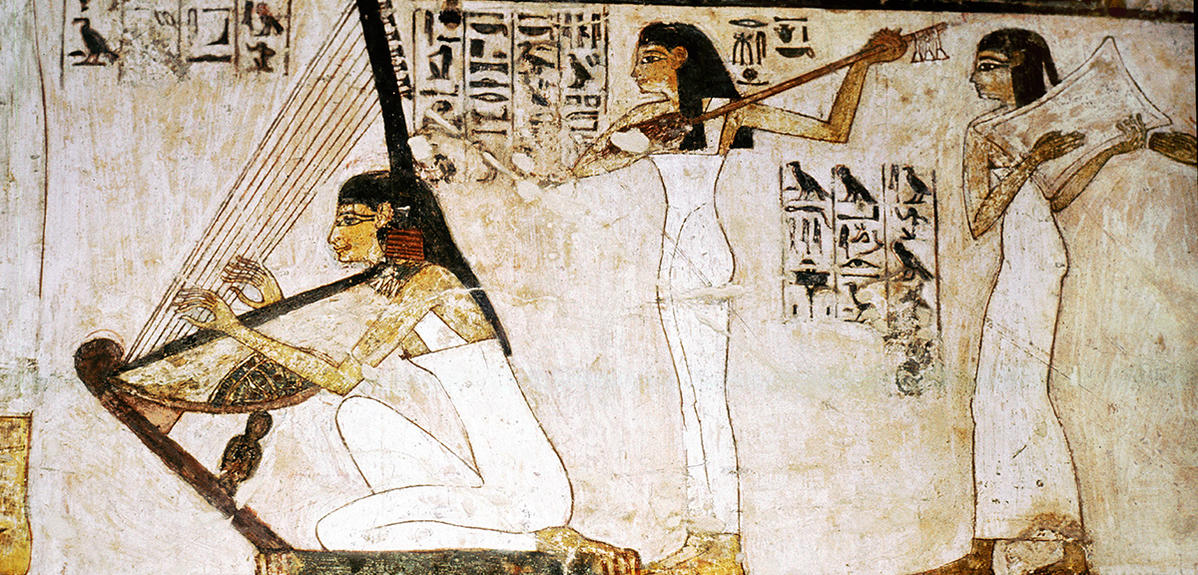

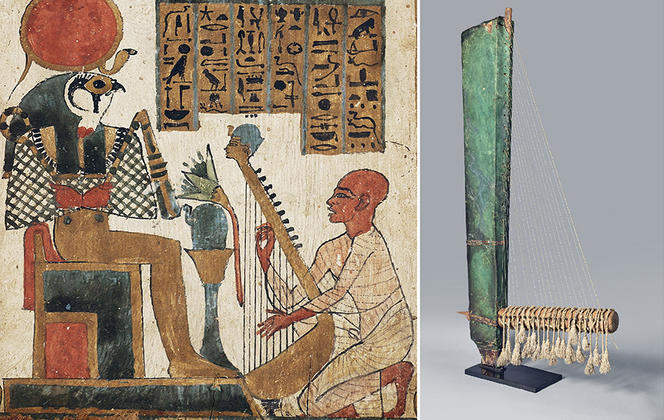

Although no scores have been found in Egypt, the country has yielded an extremely rich iconography depicting musicians of the Old Kingdom, i.e. 2700 BC, playing their instruments. “For example, the walls of tombs of the period show the recurrent theme of a concert for the dead,” Emerit says. “They depict small groups of musicians playing a harp, a flute and/or clarinet, and a singer.” In later eras, new instruments began to appear in the ensembles: the lyre, imported from the Middle East, as of the Middle Kingdom period (2000 BC), the lute and the double oboe starting with the New Kingdom (1500 BC), plus the famous trumpet found in Tutankhamun’s tomb. But the harp was by far the favorite instrument of pharaonic Egypt. Indeed, it is omnipresent throughout the three millennia of its history. “We find it everywhere in the iconography of tombs, temples, etc., and we are fortunate enough to have nearly 70 ancient specimens in archaeological museums,” Emerit says. “Most of them are angle harps, also called trigons, like the magnificent instrument lined with green leather presented in the exhibition and dated at 1500 BC. But we also have a few bow harps dating from a very short period at the beginning of the New Kingdom.”

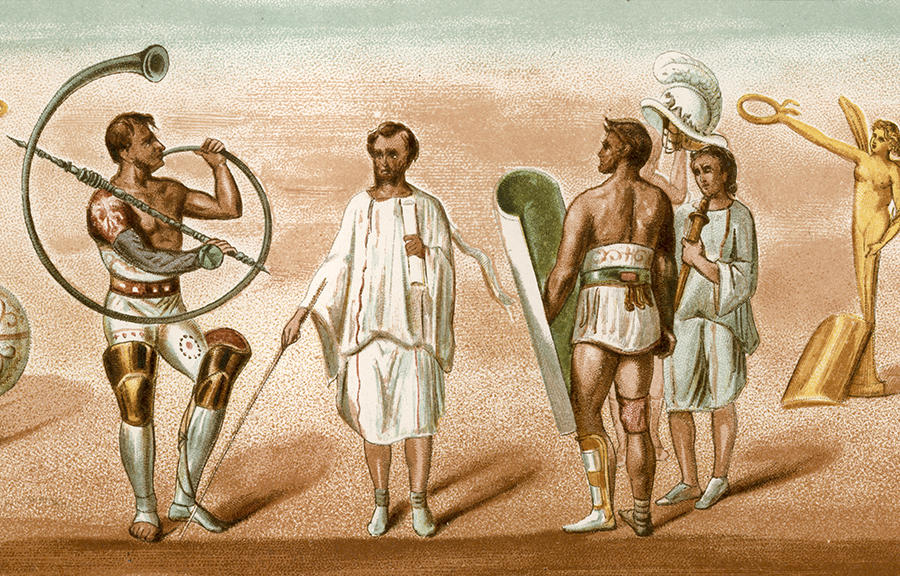

In Egypt and the Middle East, but also in Greece and ancient Rome, musicians were a constant presence in public life. They accompanied religious rites to attract the attention of the gods, they performed at important events related to social-political power, they even played on the battlefield, sounding the signal to attack, and in the parades to celebrate a victory. However, their status differed a great deal from region to region. In Egypt and Mesopotamia they were considered mere craftsmen whose only value lay in the service that they provided, while in ancient Greece and Rome some musicians were genuinely celebrated for their talent. “There was an ongoing competition among the Greek cities, with contests for musicians who played the aulos (a kind of double oboe) or the cithara, and the winners attained real celebrity,” Perrot recounts

Remembrance of sounds past

“The Romans perpetuated the custom of competitions. Some musicians earned a lot of money, were treated like stars and inspired awe,” adds Alexandre Vincent, one of the exhibition’s eight curators and a specialist in Roman history.5 “In order to avoid succumbing to the temptations of the flesh, which was believed to ruin the voice, the most dedicated went so far as to practice infibulation, inserting a pin through their genitals to ensure forced abstinence.” The supreme test of musical ability, considered the most difficult, was that of cithara accompanied by singing. “Emperor Nero, who fancied himself as a professional musician, sought glory as a competitor,” Vincent says. “He made a triumphant tour of Greece in 64-65 AD and—to no one’s surprise—won all the acclaims!”

The other Roman instruments that have survived to our day include tibiae—oboes that were often played during the sacrifices conducted to commune with the gods6—as well as several cornua of impressive size. Measuring nearly four meters in length, these curved trumpets were played in the amphitheaters during processions (pompae) and gladiator battles. Their powerful sound can be heard for the first time in the exhibition thanks to a collaboration with the IRCAM.7 “Except for a few metal percussions, most of the ancient instruments are too fragile or too damaged to be ‘sounded’,” Emerit explains. “The only way to have any idea of what they sounded like is to make copies—which has been done for an Egyptian harp, to name one example.” However, by using Modalys, a software program developed by the IRCAM, researchers were able to synthesize the sound of the cornu from Pompeii exhibited at the Louvre-Lens, based on the length and diameter of its tube and the size of its mouthpiece. It’s an archaeologist’s dream come true. Ring the sistra and sound the trumpets of antiquity!

- 1. The exhibition will run through January 15, 2018 at the Louvre-Lens before traveling to Madrid and Barcelona.

- 2. Laboratoire Histoire et Sources des Mondes Antiques (HISOMA - CNRS / Université Lumière Lyon 2 / Université Jean Moulin Lyon III/ Université Jean Monnet Saint-Etienne / ENS Lyon).

- 3. Laboratoire Proche-Orient – Caucase: archéologie, langues, cultures.

- 4. Professor of Greek history at the Université de Strasbourg.

- 5. Université de Poitiers, Laboratoire Hellénisation et Romanisation dans le Monde Antique.

- 6. Magnificently illustrated in the exhibition by two sculpted altars from the imperial period.

- 7. A collaboration between the Ecole Française de Rome, the Centre de Recherche et Restauration des Musées de France and IRCAM.