You are here

Sound in the City

In a society where image is everything, it is not easy for sound to have a voice. “Until the late 1970s, no one paid any attention to it,” recounts Jean-Paul Thibaud, a sociologist at the Centre for Research on Sonic Space & Urban Environment (Cresson) in Grenoble.1 “It was perceived as either disturbance (noise) or artistic expression (music), until a Canadian musician, Murray Schafer, became interested in the sounds of everyday life and published a groundbreaking book entitled The Soundscape (Our Sonic Environment and The Tuning of the World),2 which was translated into French in 1979. ”This “third way” led to the founding of the Cresson laboratory, entrusted with the then-pioneering mission of investigating the audio and acoustic dimensions of ordinary living spaces.

Since then, architects and urban planners, as well as philosophers and musicians, have carried out extensive field research, developing a formal grammar of sound, which has helped define some 50 sound effects that punctuate our everyday lives. These include the effects of reverberation, mostly acoustic, which are charged with symbolic meaning in Western societies as they evoke collective experiences in spaces like train stations and churches. Another example is the cut-off effect, which describes an audio environment that is suddenly disrupted, as happens when stepping off a busy street into a building, for example. “This is a signature characteristic of the space, and is widely used by architects to convey the notion of ‘before and after’,” Thibaud explains. A more pervasive effect is the background hum that has become typical of modern-day societies: a continuous sound that we no longer hear (traffic noise, the hubbub of a shopping center…), but which creates an environment of perpetual activity.

Same sound, different interpretations

By structuring the space and setting its rhythm, sound provides invaluable information, in particular to help us find our way. “Train stations offer a good example of orientation by sound,” says Nicolas Misdariis, co-director of the Perception and Sound Design team at the IRCAM.3 “Their different spaces are characterized by very specific sonic environments, which give travelers information: the echo of the main hall, the announcements on the platforms, the rumbling of the locomotives…”

However, even with a formal grammar to describe it, sound is primarily a matter of perception: the way it is interpreted can vary depending on the context or point in time. “We belong to a generation of Westerners who grew up in peacetime, and for whom gunfire is mostly synonymous with fiction and entertainment,” observes Esteban Buch, a historian at the CRAL.4 “When the first shots were fired during the November 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris, those nearby thought they were firecrackers.” A journalist for the French daily Le Monde, who lives nearby, thought that the gunfire came from the film shown on television that night. “Weapons of war in the middle of Paris was just inconceivable,” Buch adds. “The attacks changed the way we relate to the world—it will be months, or even years, before Parisians can hear a firecracker without freaking out.”

Although normally associated with peace and tranquility, even silence covers a wide range of meanings. “I am currently studying a neighborhood in São Paulo (Brazil) where the abnormal silence is actually the result of soil and water contamination by industrial waste,” Thibaud recounts. “Because of the health hazard, the space is no longer inhabited in the same way: children are not allowed to play outdoors, and people rarely get together outside their homes. The construction of new buildings and the evolution of the neighborhood have come to a halt.” According to Buch, “During World War I, silence was all but reassuring. On the contrary, it was cause for great anxiety among the soldiers, who wondered what the enemy was up to…”

Influenced by sound design

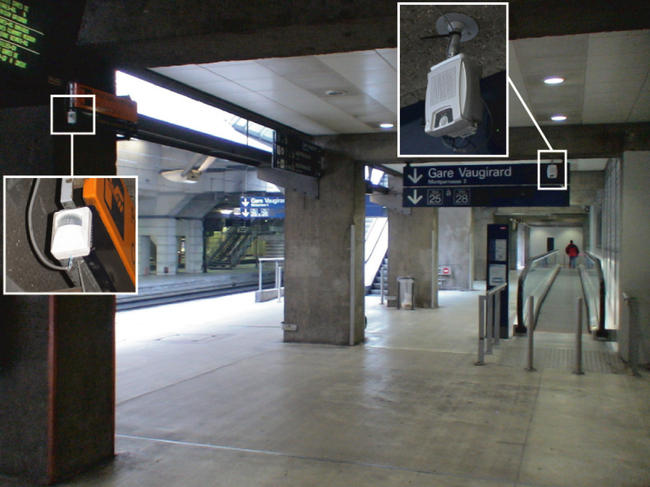

Background noise informs us about our environment, and can also be deliberately modified to influence our actions and reactions: this is the purpose of sound design. At the Montparnasse train station in Paris, a dissertation project by a young researcher named Julien Tardieu made it possible to use sound to overcome a serious problem: travelers to Normandy tended to get lost on the way to their trains, which leave from a remote section of the station, often missing their departure. “A signal system emitting short, high-pitched sounds audible above the din of the station is now triggered by sensors along the path, steering passengers to their trains without them even noticing,” Misdariis explains.

Another project supervised by the IRCAM scientist; this time in collaboration with the Paris regional authorities and a team of sound design students,5 will "give a voice" to a positive-energy building (which produces more energy than it consumes) under construction at the Cité Internationale Universitaire in Paris. One of the ideas under consideration consists in informing the student residents about the building’s energy level—i.e., whether it is fully charged or running low—by broadcasting in the entrance hall the sound of a “beating heart,” whose tempo would indicate the available energy supply. “We hope that the students will take this information into account, for example by pooling their laundry in order to run fewer machines,” Misdariis explains.

Reflecting a space and also a point in time, each sonic environment is unique. For this reason, sound researchers are also making recordings to preserve them before they are lost forever. “Today, there is a keen interest in audio heritage and sound archives,” Thibaud says. “Sound libraries are being compiled, for example to determine how a given location has evolved over time.” A mammoth task that is only just beginning…

Related topic: The Sound of 18th-Century Paris

- 1. CNRS / Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication / Ecole nationale supérieure d'architecture de Grenoble / Ecole centrale de Nantes.

- 2. R. Murray Schafer, The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World (Knopf, 1977).

- 3. CNRS / IRCAM / Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication / UPMC.

- 4. Centre de recherches sur les arts et le langage (CNRS / EHESS).

- 5. MA program, Ecole supérieure des Beaux-Arts Tours Angers Le Mans.