You are here

Is a war for water looming?

In early October 2023, President Emmanuel Macron made a two-day state visit to Switzerland with an unusual item on his agenda. The French head of state was there to formally request an increase in the flow rate of the Rhône river, which originates in Switzerland and is regulated by the Le Seujet dam, in the heart of Geneva. "The discharge of the Rhône is an extremely sensitive issue, because a large part of France's hydro- and nuclear-generated electricity depends on it," explains Stéphane Ghiotti, a geographer at the ART-Dev laboratory1 in Montpellier (southern France). Along with river transport, crop irrigation and the supply of drinking water to major cities such as Lyon, France needs water from the Rhône as a coolant for its four nuclear power stations located along the river, as well as to provide power for some twenty hydroelectric plants. The problem is that the level of the Rhône is falling at an alarming rate, especially in summer.

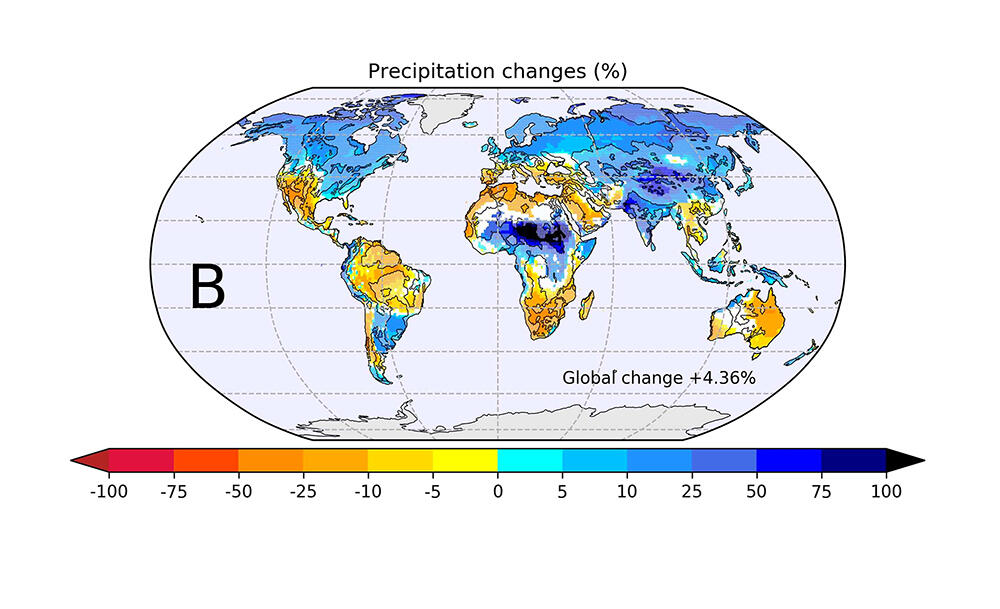

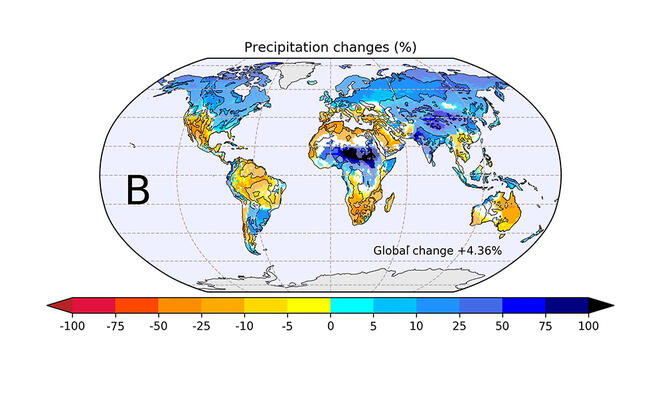

Higher rainfall, but not everywhere

Global warming caused by human activities is totally reshaping the distribution of water resources around the world by “speeding up the water cycle”, explains Bertrand Decharme, a hydrologist and modeller at France's National Centre for Meteorological Research2 in Toulouse (southwestern France). "Although there is more evaporation and therefore more precipitation worldwide, it isn’t evenly distributed." As a result, the most recent projections show that a third of the world's population is likely to see, or is already seeing, a drastic reduction in their water resources over the coming decades. "This is the case for the entire Mediterranean basin, the western United States, southern Africa, and Australia," Decharme explains. “Conversely, other regions such as northern Europe (Scandinavia, Poland, Ukraine, etc.), Canada and Alaska, the whole of Siberia, and part of southern Asia should experience an increase in their average annual precipitation."

The situation in France is harder to determine, as the country lies in the transition zone between two areas with diametrically opposed trends: northern Europe and the Mediterranean region. Although scientists are predicting, and in fact already observing, a significant reduction in water resources in the southern half of the country, they are finding it harder to model what will happen north of the Seine river. "The paradox is that many of the world's regions where water resources will increase are those that already have plentiful supplies, whereas the areas with the greatest reduction are the ones with a high level of demand, especially for farming," the researcher points out. And that's not all, since even regions where average annual rainfall is expected to rise will have to cope with fluctuating supplies due to greater seasonal variation, with wetter winters and more severe droughts in summer.

Due to these major upheavals, "international bodies, and in particular those responsible for security and defence, believe that water will become the principal source of conflict on the planet", explains Nathalie Hervé-Fournereau, a specialist in environmental law at the Western Institute of Law and Europe (IODE)3, in Rennes (northwestern France). Especially as 40% of water resources are transboundary, whether in aquifers like the Rhine alluvial water table between France and Germany, Europe's largest, or in the 250 catchment basins, such as the Rhone, Rhine, Danube, Nile, and Mekong, shared by several countries. The Tagus river, straddling Spain and Portugal, is currently the subject of dispute, with Portuguese environmental associations accusing the Spanish of taking too much water from the river as it flows through Spain on its way to Portugal, in order to irrigate vast areas of farmland in the south of Andalusia. "They are challenging the Albufeira Convention, signed 25 years ago by the two countries and which at the time provided for a transfer of water from the river to southern Spain," Hervé-Fournereau explains.

Who owns icebergs?

Rivers are not the only subject of disagreement. Closer to the poles, the question of who owns icebergs has become a hot topic of debate. For example, there have been tensions between Canada and Greenland (an autonomous region belonging to Denmark) about blocks of ice that break away from the Greenland ice sheet and drift into Canadian waters. "Canada has allowed these icebergs to be used for the production of fresh water, but Greenland contests this on the grounds that this natural resource belongs to them," the legal expert explains. And in 2018, on the other side of the world, the city of Cape Town, South Africa, was seriously considering towing a small iceberg detached from the Antarctic ice sheet to its own coasts in order to supply the population with drinking water.

"The legal status of these icebergs is not at all clear," Hervé-Fournereau points out. "The problem is that these objects are mobile, drifting around the oceans, so we don't have a clear idea of their definition. In any case, one thing is certain: with 100,000 icebergs melting at sea every year according to the United Nations, the question of their status will continue to come up, even if the cost of towing and handling them is currently prohibitive, which de facto limits their practical interest."

Another potential source of conflict is cloud seeding, designed to cause rainfall over farmland short of water. This is taking place in a context of proliferating geoengineering schemes in the US, the Middle East and particularly China, where about a hundred programmes under development are causing serious concern among its neighbours. "In some twenty French regions, seeding with crystals of silver iodide is used to neutralise hail clouds," Hervé-Fournereau explains. While the effectiveness of this technique, first developed in the 1960s, has yet to be scientifically assessed, it nonetheless raises a key question: who owns clouds?

The problem is that there is currently no international organisation responsible for regulating water use, or indeed for protecting the environment in general. An exceptional Water Conference organised by the UN in March 2023 took note of growing tensions and called on Member States to increase cooperation on the question. "But when it comes to water, governments are jealous of their prerogatives and reluctant to relinquish their sovereignty," the legal expert says.

However, the water issue is not confined to international relations. At more local levels, the increasing scarcity of this resource, or at any rate its uneven temporal and spatial distribution, is sparking public debate and raising the question of how it should be shared. For instance, the conflicts that have arisen in the west of France around plans for “mégabassines” – giant irrigation reservoirs supplied with groundwater pumped up in winter in order to irrigate crops in summer – are bringing new urgency to the subject of water use throughout the country.

Declining quantity and quality

"For decades, we in France, as in many other developed countries, thought that water resources were inexhaustible. We used them without even thinking about it," says Gilles Pinay, an ecologist and biogeochemist at the EVS laboratory4, in Lyon (southeastern France). The water cycle has undergone major transformations at every level. "Our societies had already radically altered it long before climate change came along, and have become extremely dependent on this resource," adds Florence Habets, a hydroclimatologist at the LG ENS5 in Paris. "To meet the growing needs of the industrial and agricultural sectors in particular, huge quantities of water have been rerouted by building dams and all kinds of other diversions. To such an extent that, today, half the water in the world's rivers has been diverted, much of it for human consumption, and the volume stored is four times larger than the amount of annual snowfall."

Many of these alterations are irreversible, such as the modifications made in the 1950s and 1960s to the course of the Durance river in southeastern France, one of the tributaries of the Rhône. Dams like that of Serre-Ponçon, the construction of countless irrigation canals, and the diversion of the river towards the Etang de Berre lagoon, at the very end of its journey, have radically altered its flow, which now hardly ever contributes any water to the stream of the Rhône. "The Durance is today unusual in that its discharge decreases as it flows downstream – normally, it's the other way round!" Habets points out.

The Durance is not an isolated case. In addition to engineering works, such as dams and reservoirs of all kinds designed to serve France's hydroelectric and nuclear power plants, many rivers were modified to facilitate the modernisation of agriculture. "Intensive farming led to ever larger fields, which meant changing the course of streams," Habets says. "In the wetlands of western France, the fields were drained by means of pipes buried several tens of centimetres deep to enable the use of tractors and avoid plants being waterlogged. To remove all this water, the rivers were deepened, which lowered water tables."

"Human activity has continually led to ever-faster circulation and constant drainage of water," the hydrogeologist stresses. "Today, this is proving to be highly detrimental to our adaptation to climate change." Not to mention the deteriorating quality of surface and groundwater, which has resulted in the closure of about 25% of drinking water catchments in France since 1980, further reducing the amount of this natural resource.

Debate around water usage

As a result, water usage is the subject of fierce debate: whose needs are the most legitimate, between industry, agriculture and water companies? "Broadly speaking, we know how much water is used in France. It is generally accepted that 32 billion cubic metres are abstracted annually from the surface and ground," says Ghiotti. "Of this total, it is reckoned that industry uses some 8%, agriculture 9%, waterways 6%, production of drinking water 17%, and the cooling of nuclear and thermal power stations 50%." According to the geographer, however, these figures are only indicative, as it is extremely difficult to estimate the actual quantities of water abstracted. For agricultural irrigation for instance, a great deal is withdrawn individually. In other words, it is uncontrolled or solely based on declarations. What's more, these estimates only provide an incomplete view of usage, which is in fact incredibly complex and varied in nature.

As an example, most of the water used by industry (for cooling, cleaning, etc) ends up back in the local cycle, as does drinking water which, once consumed, is treated and discharged into rivers, regardless of its quality. On the other hand, practically all the water abstracted by the agricultural sector for irrigation is taken up by crops, or else evaporates, and is not returned to the soil, aquifers or streams.

Subsequently, "If you solely consider the amount of water actually consumed, i.e. that isn't returned to ecosystems, the proportions are very different," Ghiotti points out. "Of the 4.1 billion cubic metres used in France annually, 57% is dedicated to irrigation, a practice that has been booming since the 1980s with the increasingly widespread cultivation of maize, on soils and/or in regions not always suited to this crop. The rest is shared between drinking water (26%), cooling nuclear power stations (12%), and industry (5%)."

For Pinay, reasoning based on global assessments and arguments over the interpretation of figures doesn't get you very far, especially since contexts vary widely from one region of France to another. But one thing is sure. "When you see water tables falling and more and more rivers drying up in summer, it's clear that our current methods are having an impact and that they need to be re-examined," he emphasises. But how? And by prioritising which uses? Put another way, who owns the water in France?

Sharing water

"In our country, the principle is that water is a common good, something that belongs to no one and that everyone can use. This patrimonial approach, enshrined in the French Civil Code, ensures that this natural resource cannot be appropriated," Hervé-Fournereau explains. "The only exceptions are rainwater and springs located on private property." Since the Water Act of 1964, water in France has been managed around major catchment basins such as the Adour-Garonne, Seine-Normandie, and Rhine-Meuse, by public bodies (water agencies) that bring together all the stakeholders, including local authorities, industry representatives, farmers, and users associations. "These agencies, which at one time were referred to as 'water parliaments', are supposed to ensure that water resources are equitably shared and their uses prioritised," she says.

For instance, with regard to the above-mentioned giant irrigation reservoirs being planned in western France, 80% of which are funded by public money, the Loire-Bretagne agency called for a moratorium on the building of such facilities, which are intended solely for the benefit of a small number of farmers. The decision to override this recommendation taken at the time by the central government representatives (préfets) in the regions concerned is now being appealed before the French administrative courts6.

EU bodies are also regularly approached on water-related issues, as Hervé-Fournereau explains: "Many environmental NGOs bring litigation before European institutions on the basis of a major piece of European legislation, namely the Water Framework Directive (WFD), introduced in the early 2000s with the aim of restoring the good ecological status of water agencies." This is the case for the association Eaux et Rivières de Bretagne (Waters and Rivers of Brittany), which is fighting diffuse pollution, especially by nitrates, caused by the agri-food industry. "The issue of water is a political and social one, and must be addressed democratically," Ghiotti believes. "The technical solutions put forward to alleviate its scarcity, such as irrigation reservoirs, the desalination of seawater or the controversial use of wastewater for irrigation7, should only be temporary measures and don't exempt us from the need for democratic debate."

In addition to human usage, the increasing scarcity of resources means that we urgently need to think about the equitable sharing of water with non-humans. "Ecosystems depend directly on water in soils, aquifers and rivers," Hervé-Fournereau points out. "It's worth noting that it is their needs that the Water Framework Directive cites as a priority, ahead of drinking water or agricultural requirements." She believes that we should take inspiration from international examples to advance water rights "towards a less anthropocentric and individualistic framework". In Latin America and New Zealand, some rivers have been granted legal status, while in Spain, with the Mar Menor Law of 2022, a saltwater lagoon now enjoys such protection. In any case, one thing is abundantly clear: water is a common good, and as such must be shared between humans and non-humans alike. ♦

Further reading on our website

"Les mégabassines ne résoudront pas la crise de l'eau" ("Giant irrigation reservoirs are not the answer to the water crisis") (opinion piece in French by the ecologist Vincent Bretagnolle)

9,000 years of hydraulics (interview with the geoarchaeologist Louise Purdue)

- 1. Acteurs, Ressources et Territoires dans le Développement (CNRS / CIRAD / Université Paul Valéry Montpellier / Université de Perpignan Via Domitia).

- 2. CNRS / Météo France.

- 3. CNRS / Université de Rennes.

- 4. Environnement, Ville, Société (CNRS / École Nationale des Travaux Publics d’État / ENS Lyon / ENSA Lyon / Université Jean Monnet / Université Lumière Lyon 2 / Université Jean Moulin Lyon 3).

- 5. Laboratoire de Géologie de l’ENS (CNRS / ENS-PSL).

- 6. On Tuesday, 3 October, 2023, the Poitiers Administrative Court annulled two schemes involving 15 giant irrigation reservoirs. According to the court, these projects are "oversized", and do not "take into account the foreseeable effects of climate change"

- 7. One of the concerns about the use of grey water for irrigation is its high concentration of pollutants. Although treated, wastewater still contains many chemicals such as medicines and other synthetic molecules. Until now, such pollutants were diluted in the rivers into which they were discharged.