You are here

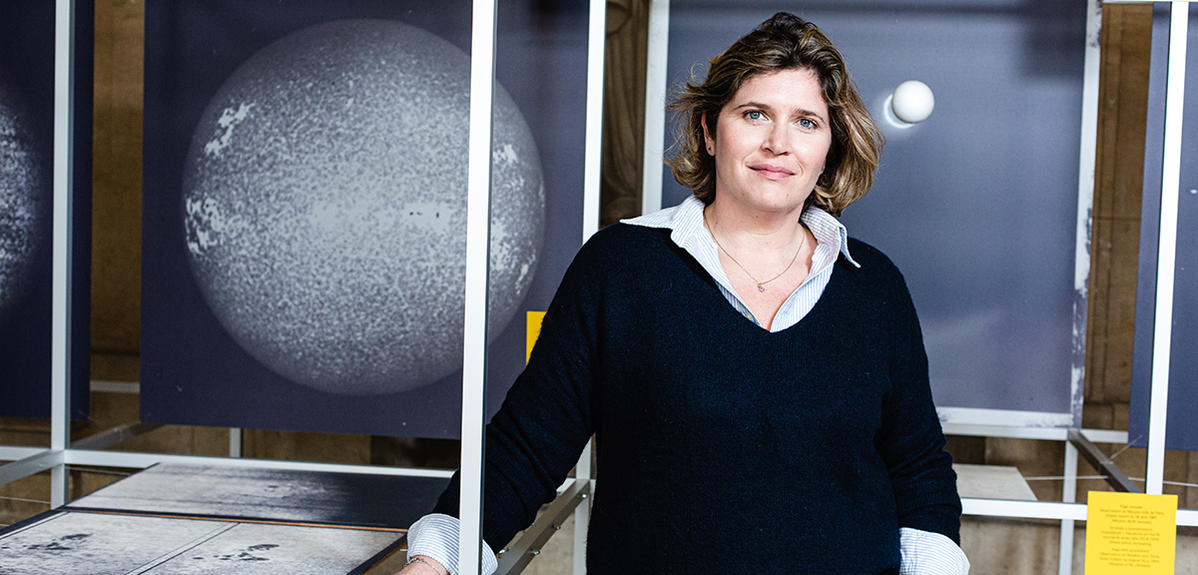

Pernelle Bernardi has her eyes set on Mars

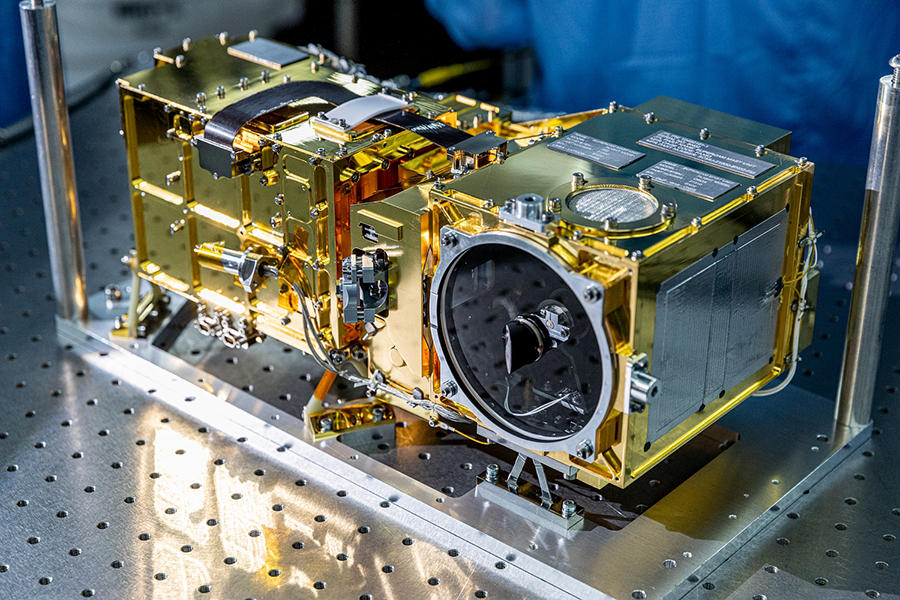

“Pressure is rising!” Just a few days before the Perseverance rover touched down on Mars on 18 February 2021, the voice of Pernelle Bernardi, a research engineer at the Laboratory of Space Studies and Instrumentation in Astrophysics (LESIA)1 was tinged with a mixture of excitement and apprehension. With good reason: the 42-year-old is in charge of the specifications and performance of SuperCam, one of the seven instruments carried aboard NASA’s rover, produced by teams from the CNRS, the French space agency CNES, and several French universities. The instrument is meant to analyse the chemical and mineralogical composition of Martian rocks and look for evidence of past life and habitability on the Red Planet.

“I joined LESIA eighteen years ago, almost by accident,” the researcher confides. In 2002, just after graduating from the IOGS (Institut d’Optique Graduate School) at the age of 24, she had no intention of working in the world of aerospace or research, but rather in telecommunications. However, the bursting of the Internet bubble in 2000 prompted her to apply to the Paris Observatory, where she obtained a fixed-term contract – her first job.

“From the moment I was interviewed I was thrilled,” she recalls. “I discovered a closely-knit team of enthusiasts. And as soon as we talked about engineering we were on the same wavelength! I was really happy to take part in this venture.”

First steps to space

She first worked on the CoRoT mission and its satellite, launched by the CNES in 2006 with the aim of searching for extrasolar planets and performing asteroseismology. After calibrating the CCD detectors and selecting the four most suitable ones for the flight, she focused on the camera, took part in the test campaign at the CNES in Toulouse (southwestern France) and at Thales Alenia Space in Cannes-Mandelieu (southeastern France), and then in the launch campaign at the Baikonur cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. “Arriving there at such a crucial time enabled me to experience this space project from start to finish, and convinced me that I’d made the right choice.” After that, things got more complicated. She joined the development team for the French-Chinese SMESE microsatellite mission to study solar eruptions, which was abandoned in 2010. The same thing happened to a project she worked on regarding a stellar seismometer intended for the French-Italian Concordia research station in Antarctica.

However, in 2013 her luck took a turn for the better. Sylvestre Maurice, an astronomer at the IRAP2 and principal investigator for the French contribution to the future US Perseverance Mars rover, contacted LESIA, a key player in infrared spectroscopy. They needed to equip the SuperCam instrument with an additional analytical technique capable of characterising rocks from a distance of several metres and telling the rover the best places to take samples from, which was a world first. Bernardi joined the project as an optical architect, and was then appointed systems engineer for the entire instrument. Her career had taken off.

The job she had been given carried huge implications. While taking into account the technical resources allocated, she had to select the best design for the instrument in order to meet the mission’s scientific requirements in terms of volume, mass, power consumption, etc. – in other words parameters that are all extremely limited for any object sent into space. As the engineer responsible for SuperCam’s overall performance, Bernardi was in charge of its technical development, not only with regard to optics but also all its mechanical, thermal and electronic characteristics, as well as the instrumentation and control system, on-board software, and external interfaces. As she explains, “one particular challenge for instance was to ensure that the laser beams remained perfectly co-aligned along the telescope’s line of sight, whatever the temperature of the instrument, from -40 °C to +10 °C, and after being exposed to shocks and vibration during the launch, the landing on Mars, and the deployment of the rover’s mast.”

The heat was on

The technical development of the instrument was to take five years. “The different stages never follow a straight line. You have to constantly check with all the architects, each of whom is a specialist in their field, that the right choices have been made,” the engineer points out.

Yet in October 2018 things went badly wrong. A technical incident occurred during a final operation and required the flight instrument to be placed in a heat chamber to speed up the polymerisation of a glue. The telescope, together with its equipment (laser, camera, and infrared spectroscope), was indeed subjected to a temperature of 250 °C, well above the acceptable limit. Unsurprisingly, it was irreversibly damaged – a complete disaster. “The team had to start all over again from scratch!” Bernardi recalls. Everything might have ended there, only a month away from the planned delivery date to the US. However, not only did the French team manage to rebuild the instrument in just six months, but they actually improved its performance! This remarkable achievement earned Bernardi the CNRS 2020 Crystal Medal , which, she stresses, “rewarded the success of the entire team”.

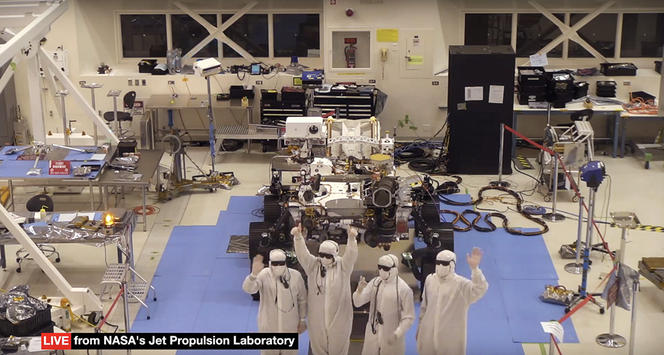

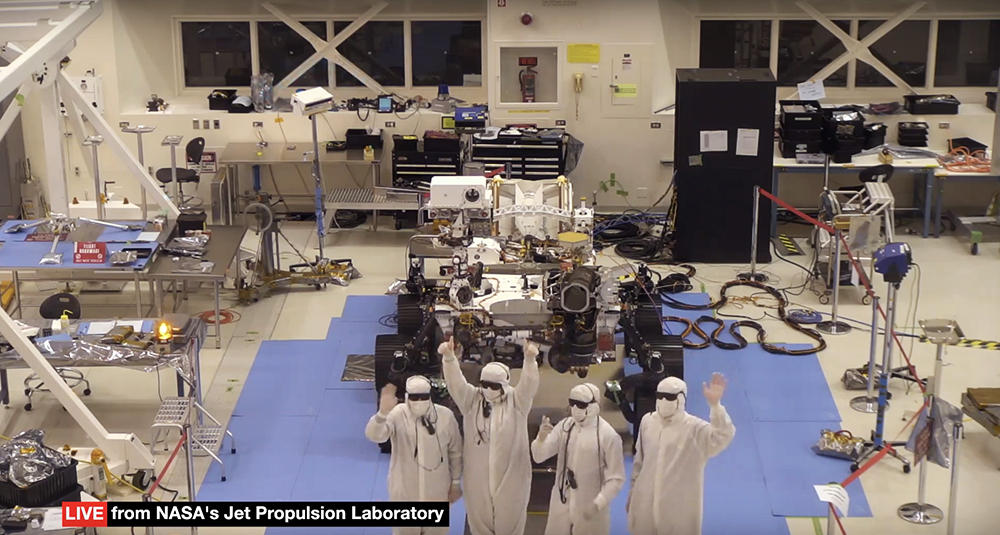

As a result, SuperCam was delivered in time to be mounted on the mast of the Perseverance rover before it launched on 30 July 2020. During the six-and-a-half-month journey to Mars, it was switched on twice, on 19 October and 12 November.“That enabled us to make sure that the instrument had got through the launch unscathed. All the data was compliant,” Bernardi explains. She is now anxiously awaiting the “health checks” that will test every function of the instrument just after the landing on Mars and before the raising of the mast, which for now is folded back on top of the rover.

Yet more Martian adventures

“This is the result of years of highly intensive work, and of very strong professional and personal commitment by all team members,” she points out. They will be on tenterhooks until the rover lands on 18 February. The stakes are huge. Bernardi’s voice betrays her enthusiasm: “We’ll be looking for evidence of life on Mars. It’s tremendously exciting from a philosophical perspective. If we detect biosignatures, then there must be life outside Earth.”

The research engineer will continue to follow the Perseverance mission until the summer. She won’t have time to be affected by the “post-project blues” as she has already been working for a year as a systems engineer on the ambitious Japanese Mars Moons eXploration (MMX) mission, whose goal is to study the Red Planet and its two moons.

This time, she has to design an infrared imaging spectrometer providing images at different wavelengths in order to map the surface of Phobos, the larger of Mars' moons, and perhaps explain its origin. Which means juggling work meetings with her Japanese colleagues in the early hours of the morning and with the American SuperCam team late at night!

Explore more

Author

Working at the daily Ouest-France since 2003, Gaël Hautemulle is in charge of sea-related content for the Brest-based editorial office.