You are here

“Energy sobriety is not just a matter for individuals”

There has been a lot of talk about ‘energy sobriety’ in recent months. What is it? How would you define it?

Sophie Dubuisson-Quellier:1 It all depends on how you approach the concept. The idea of ‘energy sobriety’ emerged quite recently, and very quickly became part of the public debate. Just a few months ago, the term was considered taboo because it conjures up the idea of punitive ecology. The sobriety being advocated today in France, and more generally throughout Europe, arose in a specific context, namely that of an energy crisis linked to the war in Ukraine. It calls for moderation in energy consumption, primarily targeting the end consumer and based on individual responsibility.

In reality though, the notion of energy sobriety has been part of social science research for about two decades. It has been the focus of many studies, mostly by British and American researchers, using the term ‘sufficiency’ – a concept that featured for the first time in the report published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2022.

What does the idea of ‘sufficiency’, which sounds different from the term ‘sobriety’, actually encompass?

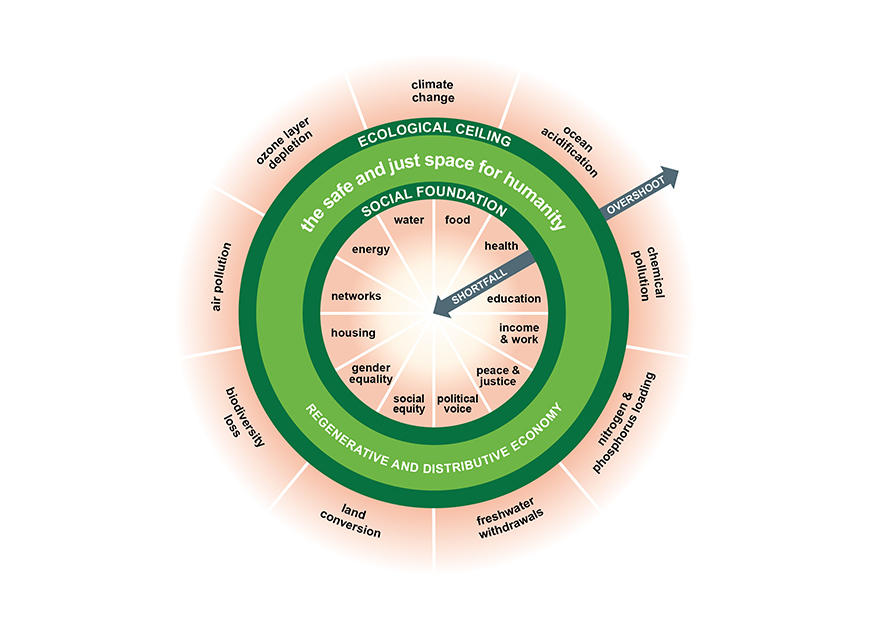

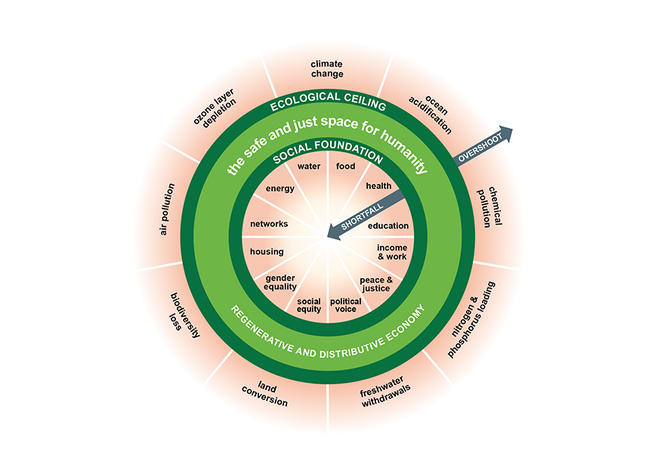

S. D.Q.: In the scientific literature, ‘sufficiency’ means moderation in consumption, but also new orientations in production and services farther upstream. It asks what is ‘sufficient’ or ‘enough’, questioning the sustainability of our way of life and suggesting the introduction of limits. Several models have been developed to this end, such as the ‘Doughnut’ model proposed by the British economist Kate Raworth, with a lower limit corresponding to the minimum threshold for meeting the needs of individuals and providing a decent life, and an upper limit representing the maximum not to be exceeded if we want to preserve the resources and habitability of our planet . ‘Sufficiency’ lies between those two limits.

The concept of sufficiency goes beyond the temporary management of a specific energy shortage. It involves redefining the levels of basic needs and well-being, and raises the question of how to decide what is sufficient and what is ‘too much’. Energy sobriety is first of all a matter of social organisation – a concept that is not taken into account in France’s current strategic thinking. It also poses a real problem for the democratic system: behind it looms the issue of the equitable distribution of limited resources in societies already characterised by deep inequalities.

In what way are social inequalities a hindrance to energy sobriety?

S. D.Q.: For individuals to change their behaviour, they must be able to choose among several options. But we know that in actual fact their decisions very much depend on their income, where they live, etc. If we want people to be less reliant on their cars, they must have viable alternatives – walking, cycling or using public transportation, for example, which is feasible in a city but much less so in rural areas. Similarly, the tenant of an accomodation with inadequate insulation and a heating system that depends on carbon-based energy has little room for choice. Consequently, the current recommendation to limit indoor temperatures to 19°C (66°F) can seem irrelevant for the 20 million French people who suffer from energy insecurity and whose homes never reach 19°C in the winter.

The way things are now, the energy transition relies largely on the will of individuals. And yet, sociological research clearly shows that the requirements imposed on each of us are vastly unequal, which greatly affects our capacity to take action. This is why studies focusing on sufficiency emphasise that factors of social justice must be a core consideration in energy sobriety policies. This implies undertaking structural actions, such as the energy renovation of buildings, in order to make it truly possible for everyone to change their behaviour.

Beyond the central question of inequality, how can energy sobriety be achieved in our so-called ‘consumer societies’?

S. D.Q.: That’s what’s called a ‘double bind’: we are asked to be frugal in a social system that is based entirely on abundance. The gains in productivity after World War II mainly served to increase production, until we reached a situation in which manufacturers had more products to offer than consumers could buy. In order to sell off these surpluses on saturated markets, the brands invest more and more into sales techniques – marketing, advertising and recently artificial intelligence – and end up producing even more in order to cover those costs and maintain an affordable selling price.

It’s a frenzied, extremely energy-intensive system that no one knows how to stop. Introducing a little energy sobriety here or there is not going to change much. Especially when public action continually encourages mass consumption, for example with car scrapping subsidies or economic stimulus policies after the Covid crisis…

Are the efforts that each of us can make, at the small individual level, useful in any way?

S. D.Q.: It’s important for people to be involved in the transition, with relevant scales of action. But that’s not enough: the sum of many small gestures will never add up to a groundswell movement. Furthermore, this limited, step-by-step policy cannot produce large-scale results, and may well discourage those who are already willing to make a huge effort, either out of conviction or because they are subject to stronger restrictions. Only society as a whole can mobilise individuals, by setting forth clear goals and the means to reach them – not the other way around.

In your opinion, what is the right collective level?

S. D.Q.: The public authorities – the national and local governments – have a crucial role to play, by taking regulatory action and showing the way forward, planning and organising the transition. But other levels of action are also possible, through companies and professional organisations, neighbourhood associations, collectively-owned properties, etc, all of which can reassess their energy use and adopt new standards.

In the scientific world, for example, we researchers often fly to attend international conferences, etc. Should each and every one of us be responsible for reassessing their own practices, or should we discuss the issue together? Making collective decisions does not necessarily mean handing down a single rule for everyone: we could consider that younger researchers at the start of their careers need to travel more in order to meet their peers. Society will evolve only if we are on a common trajectory, with each of us doing our fair share. Today’s authorities can have the feeling that the constraints required by climate change are too onerous for individuals. But in reality, certain social groups, such as farmers, are already in difficult situations and need collective change right now.

On the question of climate change and the obligatory transition that it entails, climatologists are far more sought after than researchers in the social sciences…

S. D.Q.: It is true that we are not often called upon. The biggest paradox today, though, is that climatologists are being asked to comment on social change. They might well be eager to drive this change, but they don’t necessarily have the conceptual tools for the job. The climate sciences have helped us elucidate the mechanisms and the impact of global warming. However, the phenomenon is caused by the material and institutional forms adopted by our economic organisations, by the central role of fossil fuels, the configuration of our financial circuits, the choices made in urban planning and transportation systems, and even by the way we define our goals for prosperity. The energy transition will require far-reaching changes in our economic, political and social structures, and we need the social sciences – sociology, political science, economics, anthropology, etc. – to carry it through.

- 1. CNRS research professor at the Centre for the Sociology of Organisations, (CSO – CNRS / Sciences Po Paris).