You are here

Anthropology, silence and the Mafia

Following your first ethnographic studies in various regions of southern Europe, you became interested in the Mafia. This led you to develop, notably in your books Mafiacraft: An Ethnography on Deadly Silence and La Nuit de la Parole. Écouter le Silence , a new paradigm that you call the ‘anthropology of silence’. What does this approach entail?

Deborah Puccio-Den1: It is first and foremost a critical approach: the anthropology in this field has been based primarily on interviews with ‘informants’ and the question of silence has rarely been addressed from this methodological point of view. Yet it was essential for me because my focus of study, the Sicilian Mafia, is a silent organisation. In actual fact, its mode of existence in society and in the world is silence. I therefore needed to devise a different methodological tool, inspired by the investigative techniques used and partly invented by anti-Mafia judges like Giovanni Falcone and anti-Mafia activists in Italy, the birthplace of Cosa Nostra. In Mafiacraft, I detail the investigative strategies that I had to adopt when I started working on the Mafia nearly 30 years ago, as well as the theoretical and epistemological repercussions of these methodological choices. Silence has become a powerful investigative mechanism, with great heuristic potential.

What does the term ‘silence’ mean in the context of your work?

DP-D: It is not a phenomenon defined negatively by the willful absence of words, noises, sounds, and meanings. On the contrary, I show that the silence surrounding the Mafia can be characterised by an overabundance of words that try to define it, unsuccessfully, until the legal system imposes a performative word. In addition, the Mafia has often been characterised based on what it is not, which contributes to its aura of mystery, its sacralisation. I see silence as a mode of action with its own strength and power that is used by certain social groups, including the Mafia.

What is the role of silence in this type of organisation?

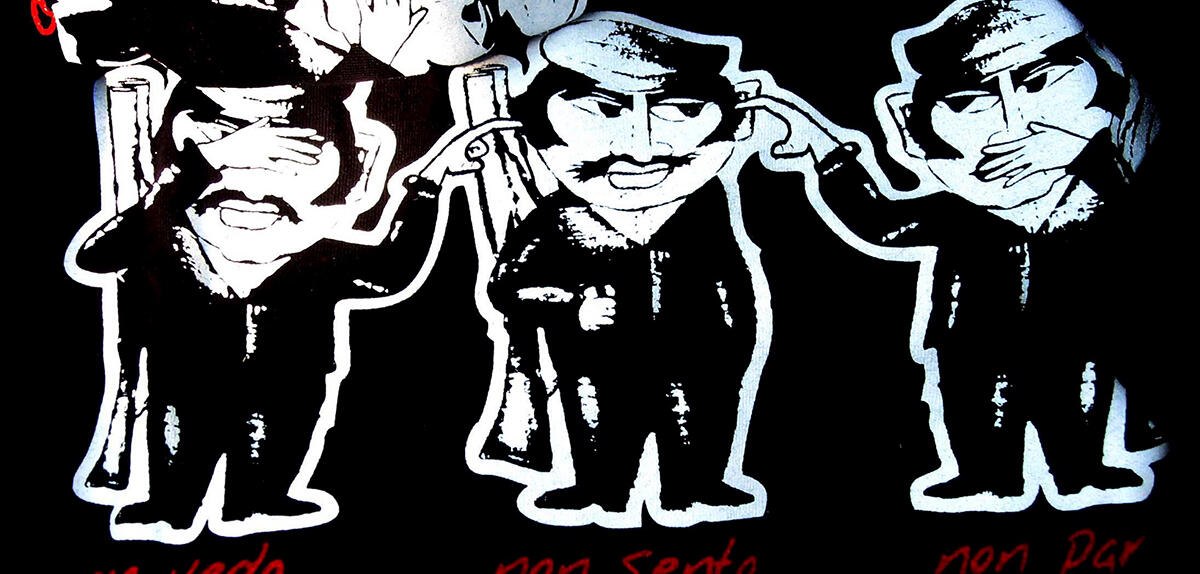

DP-D: Several ‘pentiti’ have told me about their criminal careers: they had killed hundreds of people without ever uttering the words ‘murder’ or ‘massacre’. When ‘Men of Honour’ talk about what they do, they don’t say ‘I’m going to kill this person, in this way,’ but rather ‘I’m going to do this job’ or ‘this thing’. Their silence (omerta) allows them to avoid formulating facts mentally.

Anchored in this linguistic vagueness is an action that has no real meaning for them. So for a Man of Honour, language is not a tool for describing reality but rather a means of ignoring it. The crimes of the Mafia exist in this linguistic space that I call ‘silence’, in which one cannot call things what they are. My research on this organisation was preceded by the study of Mardi Gras and the rituals of masks and unveilings2. In carnival rituals, if a masked girl was named, she had to reveal her face. Historically, this same process has taken place with the Mafia: the mask has come off, showing its true face3.

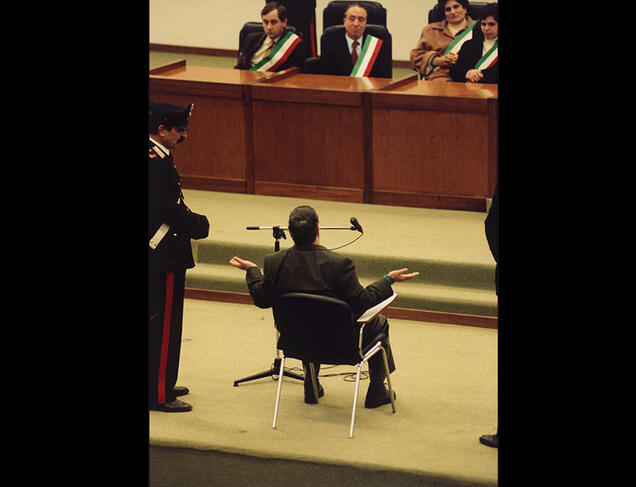

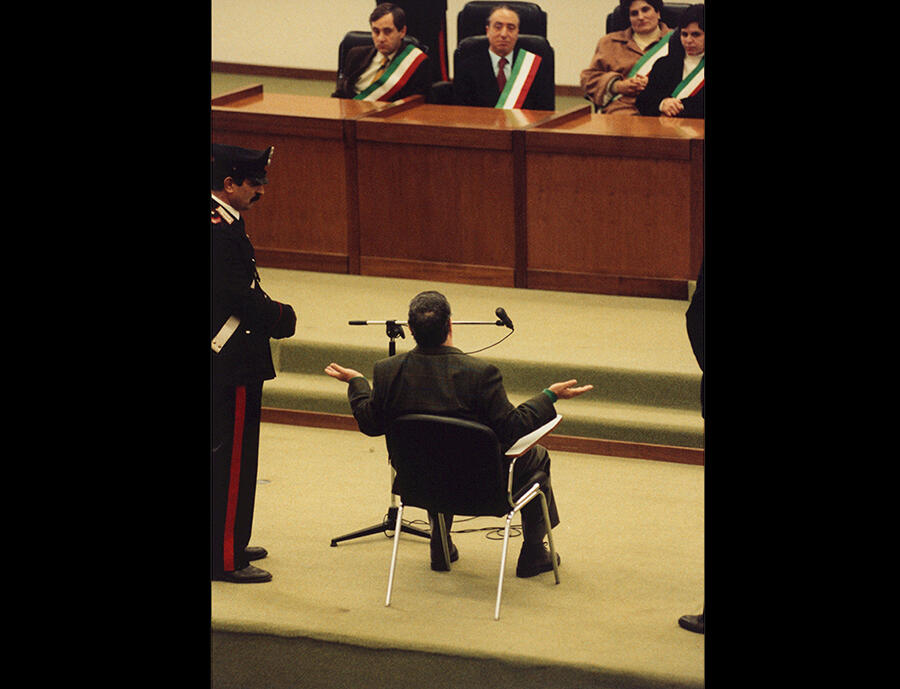

In this way, at every interrogation and trial, when linguistic processes are deployed, the Men of Honour are forced to acknowledge what they have done and admit that Cosa Nostra is a criminal organisation. Members of the Mafia cultivate a dual identity, acting as both family men and killers, with the person and the persona never perfectly coinciding.

Is it silence that enables them to accept their actions?

DP-D: Absolutely. If you don’t talk about what you’re doing, your perception of your actions is totally different. This is what makes it possible to bear the unbearable. The mafiosi become fully aware of their deeds when they become ‘pentiti’ and have to testify in front of prosecutors and judges.

This transition from silence to speech leads to earth-shattering existential crises: Men of Honour turn out to be, in the words of the pentito Antonino Calderone, ‘men of dishonour’. The first one in Italian history, Leonardo Vitale, succumbed to madness due to the haunting guilt he felt as soon as he confessed to his crimes and faced the reality of what he had done. Such contradiction can induce forms of schizophrenia. Today pentiti are granted a status that allows them to exist as such, and the transition is less drastic because they receive government support.

How do members of the Mafia refer to their organisation?

DP-D: When Judge Falcone managed to get his first pentito, Tommaso Buscetta, to testify, he was astonished to hear the man say, ‘The Mafia does not exist. It was invented for literature or by journalists. Our criminal association is called Cosa Nostra and its members are not called mafiosi but Men of Honour.’ This emic concept of Cosa Nostra – literally ‘Our Thing’ – has opened up a whole world of meanings, practices and representations. It is in fact much more meaningful than the hollow term ‘Mafia’ for Men of Honour, because it designates all the ‘things’ they have in common, especially honour. For them, this is not indicative of moral value but encompasses a set of shared substances, the first among which is blood.

In Mafiacraft you describe the Mafia induction ceremony as follows: ‘The initiator makes a cross-shaped incision on the initiate’s arm, dips a feather into it, and hands it to him, asking him to swear on the Gospel to keep the secret of the ‘venerable society’ (…) ‘The mafia member simultaneously ‘signs’ his pledge to kill and his own death sentence: he knows that should he speak, he in turn will be killed.’ Isn’t this comparable to joining a terrorist organisation or cult?

DP-D: Yes it is. Some of the pentiti I interviewed speak of their membership in the Mafia in terms of ‘belief’ and ‘ideology’, or even ‘idolatry’. Cosa Nostra, as its name suggests, is a totalitarian organisation that exacts forms of allegiance that take precedence over all other affiliations. Its members are sometimes obliged to disown their own families: when the bosses want someone killed, they call upon a member of that person’s family.

To study the Mafia without taking this existential, emotional, human aspect into account is to overlook what I think constitutes the core of the mafioso’s experience: a cognitive and linguistic attitude, an ability, and a mode of operation that makes it possible – what I have called ‘silence’.

You also note that the transition from silence to writing can open a new dimension for this type of organisation. Can you explain how?

DP-D: For Cosa Nostra, this transition took place at a specific moment in its history: when Totò Riina, the ruthless boss of the Corleonesi, was arrested in 1993. It marked the end of the so-called ‘terror strategy’ that had caused more than a thousand deaths in Italy, with massacres (attacks on Falcone and Borsellino in 1992), homicides and ‘wars’ between Mafia groups.

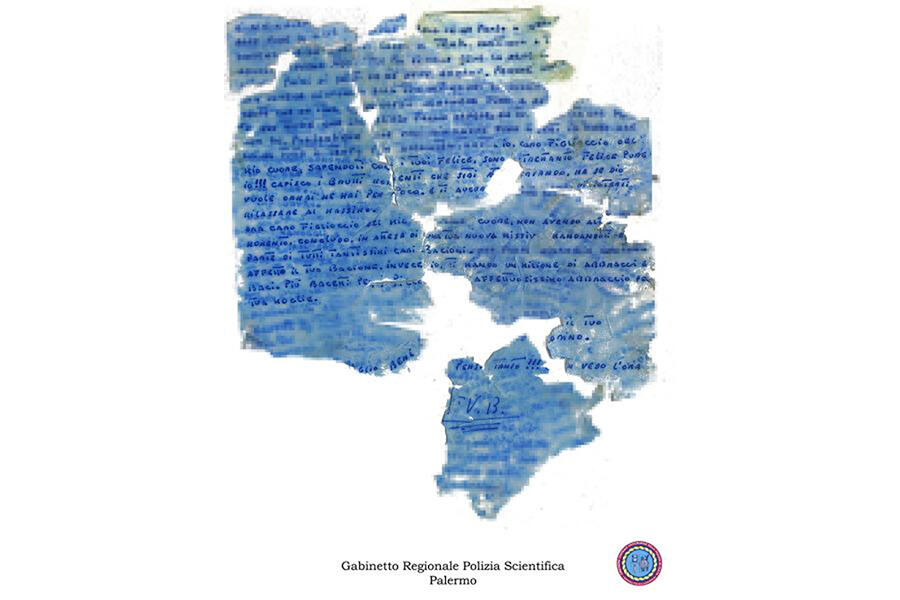

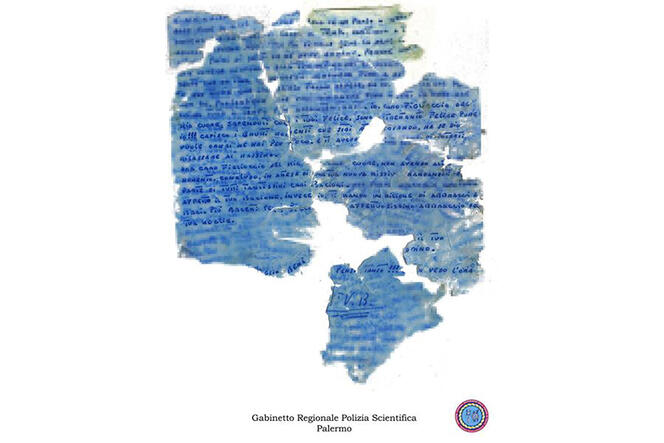

These wars have also prompted many defections among members of the losing families, who have become informants or pentiti because they cannot identify with these ‘terrorist’ modes of action, or out of fear of being assassinated. Cosa Nostra, which had had 5,000 members, was virtually decimated. At that time, Bernardo Provenzano, Riina’s right-hand man in his campaign to exterminate his enemies, tried to broker an internal peace deal, portraying himself as the great mediator and peacemaker. He operated in absentia, writing letters – called pizzini – intended to settle Cosa Nostra’s internal disputes: ‘Before shedding blood, it’s better to let ink flow first.’4

But how can ink be as persuasive as blood?

DP-D: When Provenzano established himself as the charismatic leader of Cosa Nostra, there was a sharp decrease in initiation rituals and it was his correspondents who were designated ‘Men of Honour’. They kept the pizzini with them as a kind of ID, an emblem of their membership in Cosa Nostra. These documents made it possible to sketch the outlines of the organisation and the hierarchy within it. The police were quick to identify the pizzini as tokens of recognition for mafiosi and the Mafia, and thus for the first time to formulate an answer to the question “What is the Mafia?” from the Mafia’s own point of view.

Through his use of writing, Provenzano became the central figure of Cosa Nostra. He spent his days in his ‘office’, writing on his Olivetti typewriter, and kept all the letters he received as well as copies of all those he sent out, thus compiling a comprehensive living memory of the organisation’s operations. This knowledge gave him a unique power because he was the only one who had information on everyone else. It established him as the leader. Provenzano even created a language, neither Italian nor Sicilian, that his correspondents were forced to adopt in order to write to him. Other bosses tried to imitate him in a bid to seize control but none succeeded. He also devised a numerical secret code, assigning a number to each member of Cosa Nostra. Of course, he referred to himself as ‘1’.

Has Cosa Nostra’s ‘digital revolution’ actually brought it out of silence?

DP-D: The introduction of the written word in a world of silence was a policy revolution, but when we shift our attention from the functioning of this epistolary network to analysing the content of the letters, we realise that these writings function as silence: things are still left unsaid. Mafia writing is thus another manifestation of silence. ♦

For further reading

Mafiacraft: An Ethnography on Deadly Silence, Deborah Puccio-Den, The University of Chicago Press, 2021.

La Nuit de la Parole. Écouter le Silence (in French), Deborah Puccio-Den, Société d’Ethnologie de Nanterre, 2023.

For further reading on our website

Los Ñetas, empowerment through crime?

There are many similarities between the Italian Mafia and the Asociación, a “transnational gang” that originated in a Puerto Rican prison and spread as far as Italy. But the two organisations “have no contacts or links”, the researcher Martin Lamotte reports. The work of Deborah Puccio-Den inspired him to study the place and role of the written word within the Asociación, as recounted in his book Au-delà du Crime. Ethnographie d’un Gang Transnational (in French) (“Beyond Crime. Ethnography of a Transnational Gang”, CNRS Éditions, 2022).

- 1. CNRS research professor at the Laboratoire d’Anthropologie Politique (LAP – CNRS / EHESS).

- 2. “Masques et Dévoilements. Jeux du féminin dans les rituels carnavalesques et nuptiaux” (“Masks and Unveilings. Feminine games in carnivalesque and nuptial rituals”), Deborah Puccio, CNRS Éditions, 2002.

- 3. “La Nuit de la Parole. Écouter le Silence”, Deborah Puccio-Den, Société d’Ethnologie de Nanterre, 2023.

- 4. Deborah Puccio-Den, “May God bless you and protect you!” Sicilian Mafia Boss Bernardo Provenzano’s Secret Correspondence (1993-2006)”, “Revue de l’Histoire des Religions”, 2 | 2011. https://journals.openedition.org/rhr/7778?lang=en