You are here

Los Ñetas, empowerment through crime?

This article was first published in issue 14 of the journal Carnets de Science (link is external).

For more than four years, you have been investigating the Ñetas gang, also known as the Asociación. What makes it different from other criminal organisations?

Martin Lamotte1: Los Ñetas is an organisation with impressive longevity, founded in the 1980s and still in existence today. In addition, the historical framework and transmission play a very important role, given that these types of entities usually have a shorter lifespan, lasting no longer than a generation. But the main distinguishing feature of this gang is its ambiguity. It has a dual criminal and political component: its members can be involved in the drug and firearms trade, but at the same time the group has a very strong political grounding.

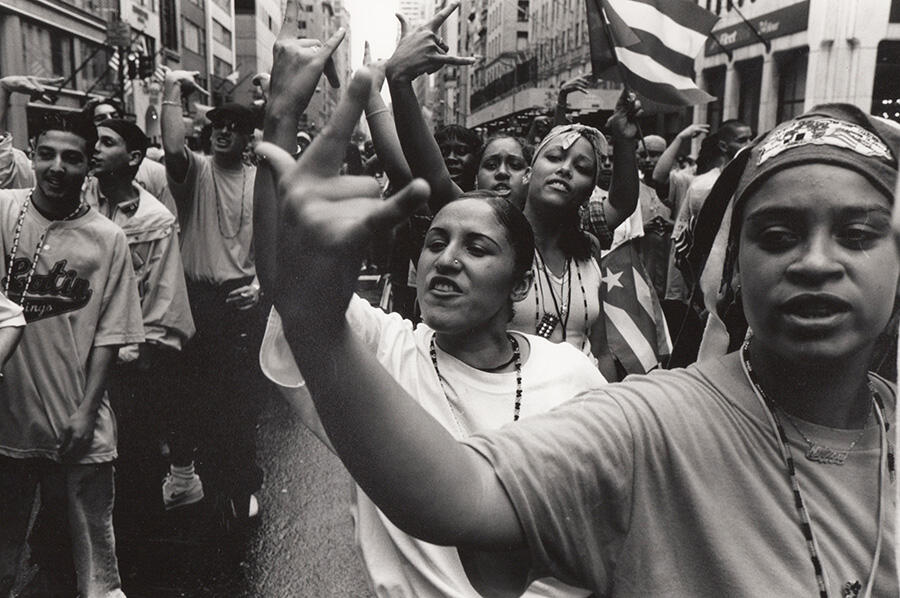

In Puerto Rico, for example, its founding leader Carlos Torres Iriarte became very close to the Socialist Party, after protecting its pro-independence political prisoners. In New York (US) in the 1990s, Los Ñetas provided security for demonstrations against police violence, encouraged young people to register to vote, and supported the political campaigns of certain elected officials in the South Bronx neighbourhood of New York City. Lastly, they have an extensive practice of keeping bureaucratic-style written records. They compile reports on their meetings and their secretaries keep accounts for the gang’s internal banking system, the fondo. Most importantly, Los Ñetas have written a book, the Liderato, recounting in detail the history of Iriarte, the association, its rules, etc. This institutionalisation of written documentation sets them apart.

Could you tell us more about the criminal history of Los Ñetas?

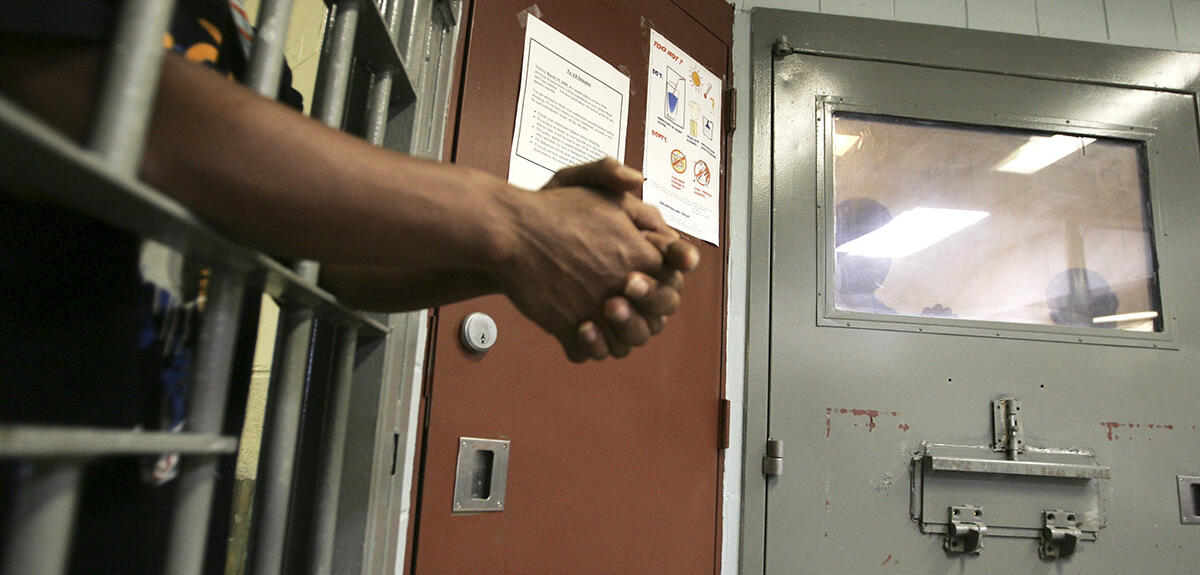

M. L.: Los Ñetas were born in 1981 in the prisons of Puerto Rico when the Asociación’s founding father, Carlos Torres Iriarte (nicknamed Carlos La Sombra – 'Carlos the Shadow'), was murdered by the rival gang Grupo 27. Although Iriarte founded the organisation, it was his friends who certified the birth of Los Ñetas, so to speak, by killing most of the members of Grupo 27 to avenge his death. In Puerto Rico, the gang was active only in the prisons.

Between 1980 and 1990, many Puerto Ricans, being American citizens, moved to New York City in one of the major economic migrations towards the United States. Those who were arrested and held in New York’s Rikers Island prison revived Los Ñetas. Then, in the early 1990s, for the first time in the Asociación’s history, it expanded outside the prison system when former prisoners formed chapters in the streets of Brooklyn and the South Bronx. But in 1994 Rudy Giuliani2, the newly-elected mayor of New York, initiated a zero-tolerance policy and cracked down on Los Ñetas, who were involved in drug trafficking. Meanwhile, the group was spreading throughout the city and beyond: two Ecuadorian prisoners from Rikers Island were deported to their home country, where they launched the Asociación in the city of Guayaquil. By the 2000s, it was established in Spain (in Madrid and Barcelona) and Italy (in Genoa), as well as the Dominican Republic, Canada and Russia.

How did you establish contact with Los Ñetas ?

M. L.: I met Los Ñetas through one of their former presidents, whom I call Bebo in my book. One evening when we were out with some young people from a neighbourhood association Bebo now works for – and I was also involved with – he started telling me about his past. We had many conversations in his office and then at his home, which built up a solid friendship between us. He finally introduced me to gang members who were still operating in New York, and wrote to the leader in Barcelona asking him to ensure my safety. But ultimately, there’s a lot of fantasising about this type of fieldwork, fuelled by the flippant posturing of some researchers. Talking to fellow anthropologists who have investigated the European Parliament, I realised that my field was much more accessible and the work in some ways easier to conduct.

The gang’s leaders told you, ‘We’re not a gang even though sometimes we act like one’. How do the members define their organisation?

M. L.: That depends on Los Ñetas and the person they’re talking to. For example, one of them explained to me, ‘We’re a gang, but not like you think: we’re revolutionaries’. Bebo told me that he had been the leader of a major gang in New York, and later claimed that Los Ñetas was not a gang. So the answer varies depending on who is talking, with whom, and when. I use the term ‘gang’ because it allows me to introduce it in the scientific literature and because the president of the New York group talks about the transition from ‘gangbanging’, meaning criminal activity, to ‘gang organising’, in reference to community organisations dedicated to improving living conditions in their neighbourhood. The term ‘gang’ is still used here, but its meaning evolves.

What kind of social and anthropological dynamics favour the emergence of this type of organisation? Are they present in all capitalist societies?

M. L. : The anthropologist Dennis Rodgers has worked on gangs in Nicaragua and drawn comparisons between them. He explains that they are geographically oriented, meaning that they reflect the local context in which they operate. They are also dynamic structures that undergo transformations over time. For example, Los Ñetas was not the same group in New York in 1990 and in Barcelona in 2011. Also, its relationship with the authorities varies. Nonetheless, it is still made up of individuals excluded from the labour market, from a form of socialisation, and often considered foreign. Los Ñetas are racialised in both Barcelona and New York, where they are among the poorest populations.

It's a rather classic phenomenon in capitalist societies. The social breeding ground plays a part, but it’s important to note that not all impoverished ghettos have gangs and gangsters. Furthermore, in the work of the sociologist Frederic Trasher (1892-1962 - Editor's note), writing in the United States in the 1920s, gangs were not defined only by criminality. It was not until the 1970s, when the Nixon administration declared war on drugs, that they started to be perceived solely from an unlawful perspective.

Indeed, although one of the major figures of Los Ñetas admits that ‘The Asociación is a movement of prisoners, so its members have committed crimes’, they also fight against trafficking and violence, in keeping with the government policy of ‘pacification’. Why do research studies, along with political and media rhetoric, focus exclusively on gang violence?

M. L.: In the United States, punitive criminology emerged in the highly repressive context of the 1970s and 1980-1990. After being perceived as the result of ghetto living conditions during the war against poverty, gangs were presented as the cause, and therefore the enemy. From a political point of view, Giuliani had no reason to admit that gangs are not purely criminal but also contribute to the pacification of underpriviledged neighbourhoods, since he wanted to impose a repressive policy.

On the other hand, the City of Barcelona and the State of Catalonia invited Bebo and members of the Latin Kings and had them sign peace treaties. Recognising them made it possible to halt the gang wars, contain their activities and build trust. It was better to work with them than fight them.

Los Ñetas often talk about justice. One leader told you, ‘Being a Ñeta is above all fighting abuse in all its forms, helping one another and progressing both individually and collectively in order to live in peace’. Is that their ideology?

M. L.: Yes – one of their mottos is ‘Progresar y vivir en paz’ (“Progress and live in peace” – Editor’s note). It appears on the title page of the book Liderato, which shows its importance. Originally it was about fighting the abuses of the prison administration, but the idea has been extended to all types of abuse.

The Asociación eventually gained official status in several countries, leading its members to negotiate with political forces, including the police. Was this institutionalisation necessary for the group’s continued existence?

M. L.: It is indeed important to see what remains of Los Ñetas in light of this pacification and institutionalisation. In Barcelona, they are acknowledged as a social and political force. They have been legalised in Ecuador and the State of New York recognises the Asociación Pro Derechos Del Confinados Ñeta Inc. NYC as a charity. The leaders know how to manage a group, handle young people, so it’s in the public interest. However, in New York their pacification coincided with a phase of internal transformation and decline, which involved other elements: the deterioration of the crack market, heavy sentencing for small-time street vendors, the gentrification of New York, the increasing precariousness of their life paths…

Why do the members of the Asociación abide by quasi-religious rules, with a strict hierarchy and the possibility of severe punishment for violations, reproducing what they fight against outside of their own organisation?

M. L.: They reproduce the kind of organisation that they know, but with the key difference that they are recognised. Within the Asociación they can be Puerto Ricans, Latinos, and proud of it. They proclaim their otherness, turning the stigma around. ♦

For further reading

Au-delà du Crime. Ethnographie d’un Gang Transnational (“Beyond Crime. Ethnography of a Transnational Gang”, in French – link is external), Martin Lamotte, CNRS Éditions, 2022.

- 1. Martin Lamotte works at the CITERES (Cités, Territoires, Environnement et Sociétés) laboratory (CNRS / Université de Tours).

- 2. Mayor of New York from 1994 to 2001 and a lawyer by training. A member of the Republican Party, Rudy Giuliani was one of the leading figures in the American judicial system under the Reagan administration, serving as Associate Attorney General and later Federal Prosecutor of New York.