You are here

Allergies: towards New Therapeutic Options

Your team at the IPBS1 in Toulouse is well known for its research on the mechanisms of allergy. Can you remind us what an allergy is?

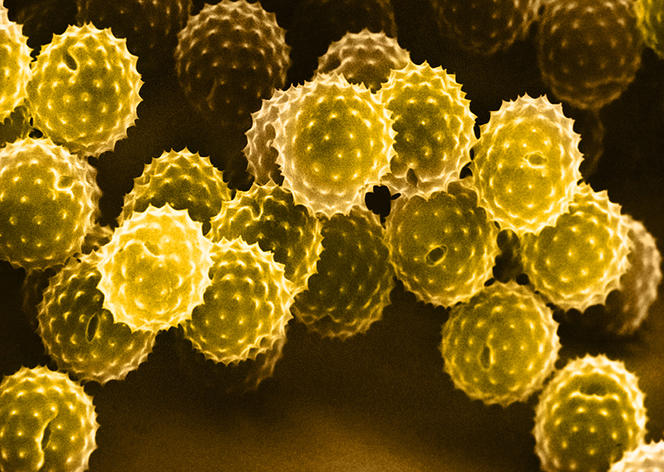

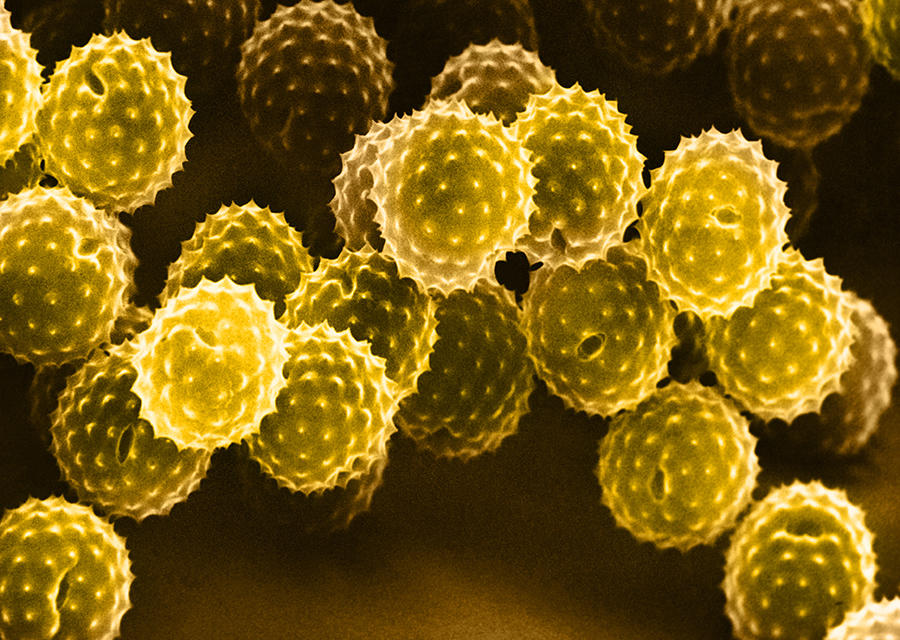

Jean-Philippe Girard: It is an abnormal, excessive and inappropriate reaction by the immune system to harmless substances called allergens: pollens, dust mites, molds, animal hairs, wasp venom and some foods such as peanuts, etc. It can occur at any age, and is caused by two factors: genetic predisposition and exposure to an allergen.

Corinne Cayrol: the symptoms of allergies are sneezing, a runny and blocked nose in the case of rhinitis (hay fever), difficulty in breathing and wheezing in that of asthma, itchy red plaques on the skin in eczema sufferers, while itching, swelling of the eyelids and red eyes are symptomatic of allergic conjunctivitis and swelling of the mouth, nausea or abdominal pain are characteristic of food allergies. Too often considered to be trivial, these symptoms impair quality of life and productivity at work or school. They cause sleep disorders, fatigue and irritability. In some cases, such as peanut allergy, they may even trigger a violent and potentially fatal reaction, called anaphylactic shock.

Today, nearly 30% of French people suffer from an allergy, compared with only 3% in 1970. By 2050, this percentage will have risen to 50%. What is the reason for this dramatic rise in allergies?

J.-P. G.: There are several factors: global warming, pollution, changes in our lifestyle and our environment, and exposure to new foods due to globalization.

C. C.: Global warming, for example, increases pollen concentrations in the air, the duration of peak pollination, as well as pollen varieties. A rise in temperatures thus enables plants that are normally found at other latitudes to flourish in France. This is notably the case for ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia L.), a plant originating from North America that has a highly allergenic pollen and in recent decades has colonized the Burgundy, Auvergne and Rhône-Alpes regions of France.

J.-P. G.: In terms of changes to our lifestyle, one hypothesis is that the trend towards improved hygiene in developed countries has resulted in less exposure to infections during childhood. Our immune systems have therefore become more sensitive to foreign substances, whether they are dangerous or not.

C. C.: Another point regarding lifestyle is that we are using more and more chemical substances that alter our epithelial barriers (skin, nasal or gastric mucosa, etc.), such as cosmetics, detergents or food additives, which cause 4% of food allergies. Furthermore, pollution—and particularly fine diesel particulates—worsens the symptoms of respiratory allergy or asthma.

What are the mechanisms underlying allergies?

C. C.: The allergic reaction occurs in two stages. The first so-called sensitization phase corresponds to the initial contact with the allergen. At that point, when there are no clinical signs, the immune system produces type E immunoglobulins (or IgE) which are antibodies specific to this allergen. The second stage starts as from the second exposure to the allergen and consists in the allergic reaction itself. At this point, the allergenic substance is recognized by the IgE fixed on immune cells called mastocytes. As a result, these cells release a whole series of molecules (such as histamine), which induce the inflammation that gives rise to allergic symptoms.

What are the best treatments against these disorders?

J.-P. G.: There are several, in the knowledge that our therapeutic arsenal has expanded in recent years. But before looking at medication, it is important to remember that the best strategy is to avoid exposure to allergens as much as possible; for example, by driving with the windows closed and avoiding to walk in the countryside during the pollination period for hay fever sufferers.

C. C.: For simple allergies such as allergic rhinitis or conjunctivitis, or even mild to moderate asthma, the first-line treatment consists in antihistamines, combined or not with corticosteroids. These are non-specific treatments designed to alleviate the symptoms. If they prove ineffective or insufficient, another solution may be desensitization.

What does desensitization involve?

C. C.: This is also referred to as allergen immunotherapy. Designed to act on the actual cause of the condition, it is administered as a priority to individuals suffering from allergies that are resistant to standard treatments, and whose allergen has been identified. In practice, the objective is to render the patient tolerant to the irritant by exposing them to increasing doses of it in subcutaneous injections or via the sublingual route. Desensitization can improve symptoms in 70% of cases of allergies to dust mites and grass or birch pollens, and in 95% of hypersensitivity to wasp stings. However, it is not effective against skin and food allergies.

What are the latest treatments that have now become available?

J.-P. G.: The past ten years have seen the introduction of two types of treatment for severe asthma, which affects 300 million people throughout the world. These are antibody-based therapies that aim to block either IgE (Xolair®, authorized in France since 2009) or interleukin-5 (IL-5), a cytokine involved in the activation of eosinophils, which are key cells in allergy. In 2016 and 2017, two IL-5 blocking products were approved in France: Nucala® (mepolizumab) produced by the UK giant GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), and Cinqaero® (reslizumab) from the Israeli company Teva. That said, these drugs are reserved for severe asthma sufferers who are also producing large quantities of eosinophils. It is therefore urgent to develop other courses of medication that can target all types of severe asthma. One therapeutic target raises much hope in this case: interleukin-33, or IL-33.

What is it?

J.-P. G.: It is a human protein that was discovered fortuitously by our team in 2003 while we were working on a completely different project: the characterization of specific blood vessels called HEV.2 Over the past 15 years, our work and that of other teams has demonstrated the crucial role of IL-33 in allergic inflammation and predisposition to asthma in humans.3

How is it involved in asthma?

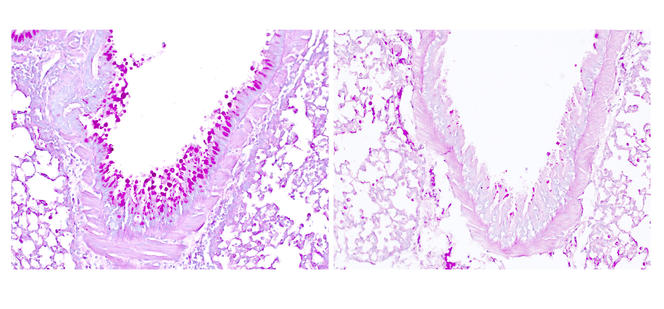

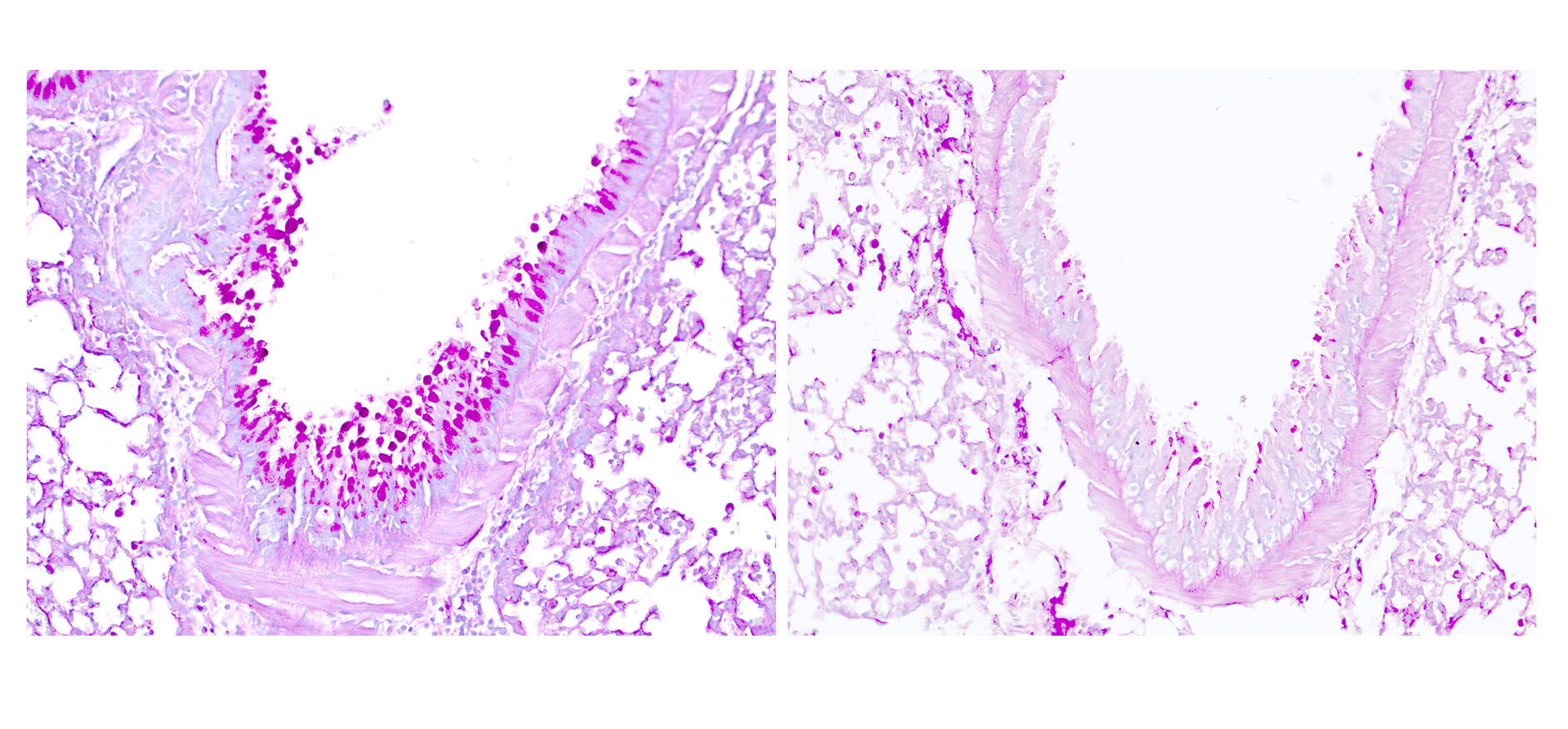

C. C.: Our studies published in April 20184 show that the respiratory allergens that are responsible for asthma, such as pollens, molds, dust mites or irritants related to working conditions (such as the subtilisin enzyme used in the detergent industry, etc.), contain enzymes called proteases that can generate hyperactive forms of IL-33. These ultra-powerful signals activate immune cells that resemble lymphocytes: type-2 innate lymphoid cells, or ILC2, whose role is to produce large quantities of two major cytokines in allergy: IL-5 (which we have just mentioned) and IL-13. Hence the exacerbated allergic symptoms observed in asthma, such as an excessive production of mucus, which makes breathing difficult.

How can the effects of IL-33 be blocked?

C. C.: The idea is to develop antibodies that block this protein or its receptor, ST2, to halt not only the production of IL-5 (which is how the recent treatments described earlier operate) but also that of IL-13. And this regardless of the form of severe asthma—with or without excessive eosinophils—unlike the latest treatments that target IL-5.

How advanced is pharmaceutical research in this area?

J.-P. G.: Several clinical trials are already underway in severe asthmatics. No fewer than four pharmaceutical multinationals have entered the race: Roche-Genentech in the US, GSK and AstraZeneca in the UK, and Sanofi in France. The latter two are conducting phase I trials aimed at evaluating the efficacy of a candidate therapy in a few tens of patients. GSK and Roche-Genentech have already initiated phase II trials, which seek to assess the effectiveness of a treatment in several hundred patients.

Could treatments targeting IL-33 be used in allergies other than severe asthma?

J.-P. G.: Yes. The American firm AnaptysBio is testing antibodies which block IL-33 in patients with atopic dermatitis—a skin allergy—and peanut hypersensitivity. In the former case, the initial results seem to be encouraging. That said, the only solid data obtained to date mainly concern asthma.

When might these treatments become available?

J.-P. G.: In two to three years’ time, if all goes well.

- 1. Institut de Pharmacologie et de Biologie Structurale (CNRS/Université de Toulouse III - Paul-Sabatier).

- 2. Particular blood vessels which constitute portals of entry for lymphocytes into the tissues and notably into cancerous tumors, thus favoring their eradication.

- 3. C. Cayrol and J.-P. Girard, "Interleukin-33 (IL-33): A nuclear cytokine from the IL-1 family,"" Immunological Reviews, 2018. 281 (1): 154-168. DOI:10.1111/imr.12619

- 4. C. Cayrol et al., "Environmental allergens induce allergic inflammation through proteolytic maturation of IL-33, ,"" Nature Immunology, 2018. 19: 375-385. Doi.org/10.1038/s41590-018-0067-5

Explore more

Author

A freelance science journalist for ten years, Kheira Bettayeb specializes in the fields of medicine, biology, neuroscience, zoology, astronomy, physics and technology. She writes primarily for prominent national (France) magazines.