You are here

A capsule to explore the intestine

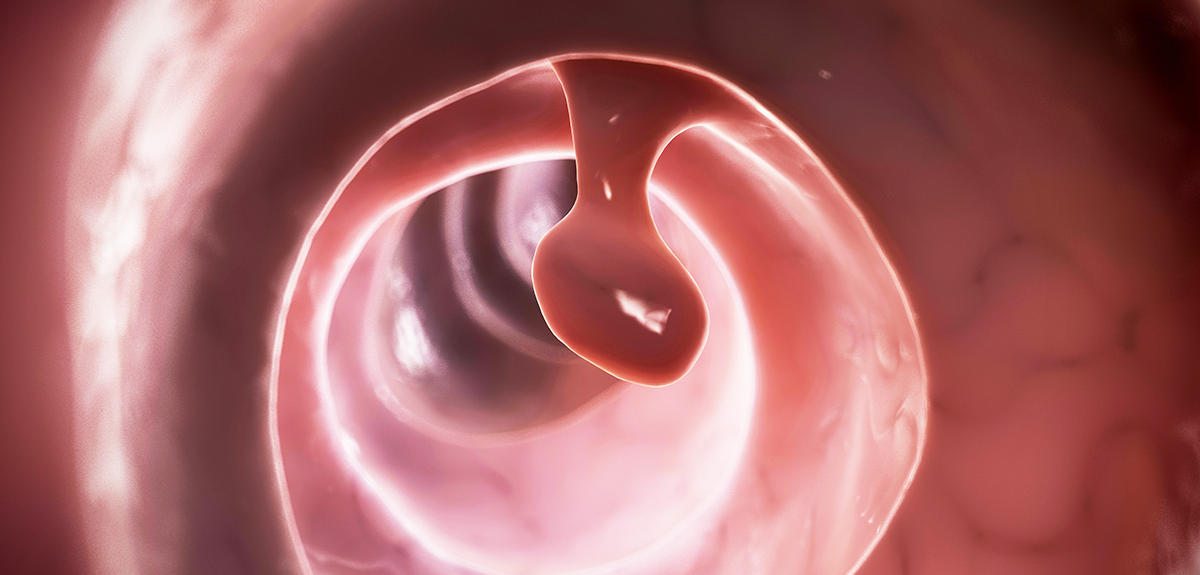

Undergoing a colonoscopy under anaesthetic is certainly not much fun, so to spare their patients the discomfort, physicians will soon be able to give them a small technological miracle to swallow: an endoscopic capsule equipped with a camera and 3D imaging system. The size of a large olive, this autonomous probe called Cyclope will then travel through the digestive tract, where it will produce a detailed map of the colon and intestine. If abnormalities such as polyps are present, the capsule will be able to detect them.

This bears all the more relevance as in France, colorectal cancer is the second deadliest cancer. Screening is recommended once every two years for all individuals aged from 50 to 74 years. More than 40,000 new cases are detected annually, and with the ageing of the population, this number is likely to rise in the near future. Any innovation that can facilitate screening, or even management, will therefore be more than welcome.

The Cyclope capsule is being developed under the supervision of Andrea Pinna, Amine Rhouni, Bertrand Granado and Orlando Chuquimia, from the LiP6 laboratory.1 The project, which has just been included in the CNRS Innovation Pre-Maturation Programme, should be an important step forward in the design of intelligent screening tools. “Endoscopic capsules date back to the 2000s,” explains Bertrand Granado. “They are mainly used to explore the small intestine, which is inaccessible by colonoscopy. The problem is that they produce low- resolution images and the gastroenterologist analysing them is forced to watch the entire film to detect any abnormalities. This is evidently very time-consuming.”

The search for polyps

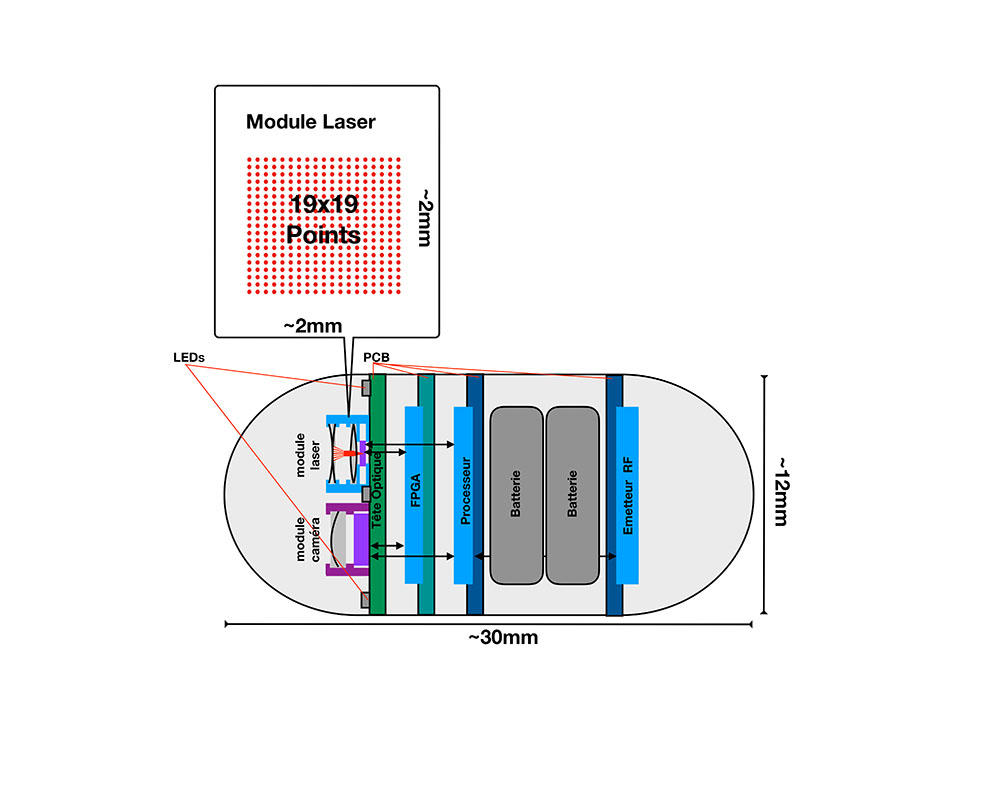

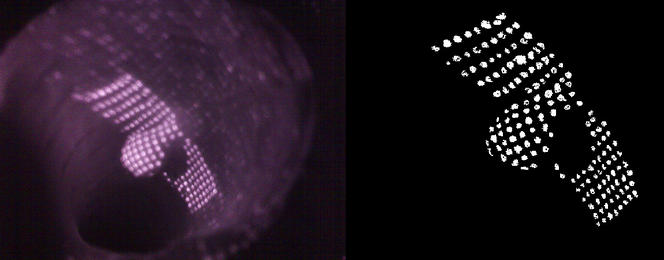

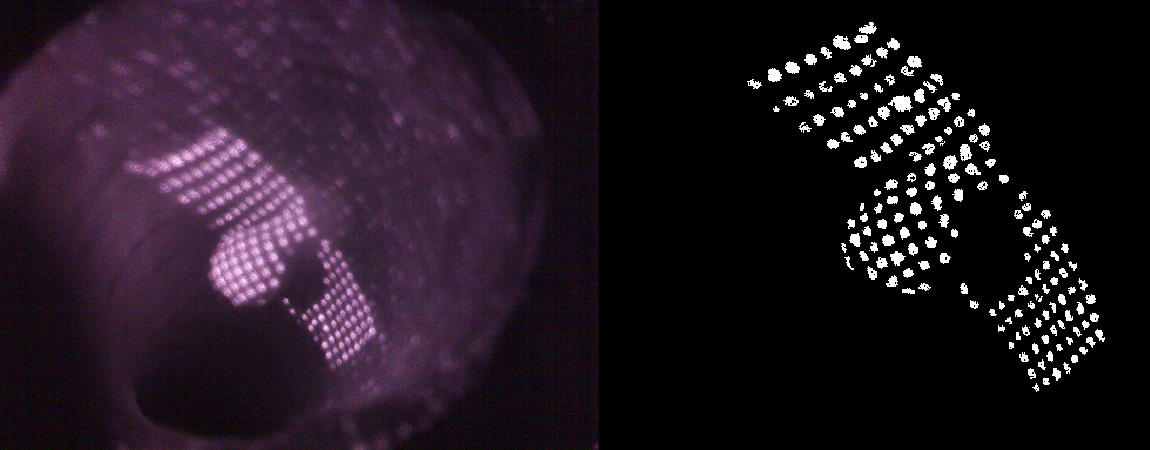

Cyclope promises to remedy those difficulties, as it will be equipped with a megapixel camera and LED lighting that will generate high-definition images. Above all, it will contain an imaging system able to map the interior of the colon with an accuracy close to 90%. To achieve this, the capsule will project a laser pattern on the intestinal wall and based on deformation of this pattern by the volume of the digestive tract, it will be able to reconstitute its relief.

This should prove quite revolutionary in terms of diagnosis. Indeed, the best markers for colorectal cancer are polyps, outgrowths from the colon wall that can evolve into malignant tumours. Yet the cameras used for traditional colonoscopies generate flat images, so the gastroenterologist carrying out the examination sometimes finds it difficult to evaluate the size of polyps and hence the danger they represent. Using the 3D images from Cyclope, the specialist will know immediately which to remove urgently and which can be kept under observation.

And that’s not all. Cyclope’s artificial intelligence systems will enable it to identify images showing polyps and only transmit these. This way, “the specialists will not have to watch hours of film. They will be able to focus on a few important shots,” the scientist explains. This will save considerable time and effort, which is by no means anecdotal from a public health standpoint. In France, 1.3 million colonoscopies are performed each year and 80% of them reveal nothing abnormal. Intelligent capsules such as Cyclope will spare gastroenterologists the trouble of analysing millions of negative screenings each year! This in turn will make it possible to step up testing of the entire at-risk population.

Furthermore, the use of endoscopic capsules will avoid the dangers associated with standard examinations. It requires no anaesthesia and the risks of retention or damage to the intestinal tissue are close to nil, even in elderly and frail patients. Cyclope could be swallowed at home and easily excreted some twelve hours later. During this period, the images emitted by the probe would be recorded by a device worn on the belt. This simplified process could also contribute to increasing the number of colonoscopic examinations.

Fantastic voyage

“I sometimes make an analogy between this project and Fantastic Voyage,” the researcher says, referring to the sci-fi film issued in 1966, which recounts how a submarine and its crew are miniaturised and sent on a mission into the body of a scientist in a coma. “The difference is that in our case, the crew is replaced by artificial intelligence.”

What in 1966 was pure science fiction is now in its research and development phase. The LiP6 scientists are trying to address a double technological challenge. First of all, they need to reduce the imaging system so that all the elements in the capsule – laser source, convergent lens, camera, processing unit, data transmission system and two button cell batteries, can be contained within a cylinder measuring 1.4 cm in diameter by 3 cm in length. In addition, the team needs to optimise energy consumption so that the probe has twelve hours of autonomy, the duration of intestinal transit. The scientists have given themselves eighteen months to achieve these goals, which will constitute proof of concept. “We shall then be able to present the project to industrial firms or postulate for European programmes,” the scientist hopes. In two years, a prototype may be ready for testing in animal models.

This undertaking is only a foretaste of what intelligent medicines could do for us. “A potential scenario could involve a capsule with a reservoir containing a drug that would be delivered directly to affected regions, such as ulcerated tissues. Or a capsule with a robotic arm able to excise polyps and collect tissue samples.” Like a mission to Mars, such developments are obviously some way away. But the number of functions for these medical probes will only continue to expand.

Their field of application could also be extended. “These devices would indeed be invaluable in developing countries that face a shortage of specialists, as they facilitate remote diagnosis. They could also be of use during long-term space missions.” Autonomous capsules such as Cyclope truly herald a new era of medicine with unlimited potential.

- 1. Laboratoire d’Informatique de Paris 6 (CNRS / Sorbonne Université).