You are here

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights Turns 70

“I ask myself often, imagine we, the international community today, would have to establish such a declaration on human rights. Would we manage that? I fear, not.” This remark, referring to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) adopted by the United Nations on December 10, 1948, was made by Angela Merkel at the Paris Peace Forum, held on November 11-13 of this year.1 Even though the German chancellor softened her tone by using the interrogative form, her question draws attention to the extraordinary political regression taking place today on every continent. In Eastern Europe and Latin America, extreme right-wing governments are passing laws that restrict individual liberties, in particular the rights of women, freedom of the press and academic freedom. In the United States, the current presidency occasioned a resurgence of "feelings" of racism, homophobia and misogyny. In Myanmar, Aung San Suu Kyi's human rights award, presented to her by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum for “resisting tyranny and advancing freedom,” was revoked due to her failure to intervene in the Rohingya crisis. And the list goes on…

Demeaning human rights has become the predominant line of political discourse. The breakdown of the family? The blame is on human rights, said to have transformed what used to be a collective entity into a simple association of individuals with equal rights (women, children, etc.). Elected officials are having trouble governing? It’s down to human rights, which, by allowing everyone to demand the right to healthcare or housing, has made the construction of a general will impossible. The market economy has been legitimised? Human rights are to blame. Populism is on the rise? It’s because of human rights.

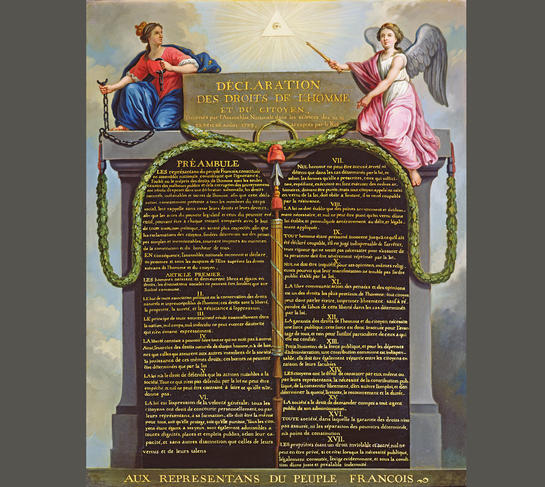

In France as well, this point of view is upheld by intellectuals—obsessed with the past—who have forgotten that the preamble to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, adopted by the new French government in 1789, states that “the ignorance, neglect or contempt of the rights of man are the sole cause of public calamities and of the corruption of governments.”

Seventy years after the adoption of the UDHR, we must emphasize, and re-emphasize, that human rights are the key to democracy. First of all because they establish the notion of citizen, the referent of democracy. When people band together, their union creates the need for rules that frame their community life and interrelations—which, to borrow a phrase from Article 2 of the Declaration of 1789, recognises them as a “political association.”

There can be no society without rules. And, when societies dissociate themselves from religion, and more generally from any form of transcendence in which to anchor the rules of political integration, the only secular medium remaining for “forming a society,” perpetuating it, regulating it and determining the collective (i.e. political and historical) destiny is legal rights.

Citizen of rights

In post-metaphysical societies, without rights there can be no politics and no history—only a social void and anomieFermerA concept originated by Durkheim, anomie characterises the situation in which individuals find themselves when the social rules that frame their behaviour and aspirations lose their power, are incompatible among themselves, or when, undermined by social change, they must give way to other rules.. Thus, by specifying a list of human rights, the UDHR offers people of all countries the possibility of “escaping” their predetermined social roles, of no longer perceiving themselves in terms of social differences but rather as beings with the same rights, as citizens of the world. The intrinsic power of a legal right, according to the writings of Pierre Bourdieu, is to establish, in other words bring into existence or give life to, what it defines. This holds true for human rights, which define citizens, and by doing so establish them as legal persons. Indeed, the citizen is neither an immediate entity of the conscience nor a natural entity. The notion of citizen is not an objective reality but rather an artificial creation—actually resulting from the laws specifying the rights that establish it.

Rights, an open question

Secondly, human rights are the key to democracy in that they bring people together (through freedom of movement, of expression, etc.) to set the rules of society, and in that they open the way to history, being always in front of us, to be discovered and implemented. The right to equality (declared in 1789), to housing (1946), to a healthy environment (2004): these remain rights to be achieved, and should not be considered acquired on the pretext that they date back to 1789, 1946 or 2004.

Human rights are not “closed” freedoms but rather, as Claude Lefort put it, “freedoms of interaction”.2 When Article 6 of the Declaration of 1789 recognises the citizens’ right to participate in the making of the law, it incites them to interact with each other to define the general will. When Article 4 defines freedom as the ability to do anything that does not harm others, it prompts individuals to consider the existence and rights of other people.

When Article 11 declares the free communication of ideas and opinions, it encourages people, rather than turning in on themselves, to remain open and join forces with others.

In other words, the Declaration of 1789 eradicates the closed system of the Ancien Régime, replacing it with an open system. What human rights introduce is not the delimitation of a private space in which each one is enclosed, sealing themselves off, but on the contrary the creation of a public space where each person and their ideas can circulate freely, by necessity interacting with other individuals and their ideas.

The democratic distinction is precisely rooted in this ongoing examination of the question of human rights. Totalitarian regimes, like democratic regimes, no doubt “operate” via legal rights. But while the former reject, in principle, any discussion of rights, of which they claim to be the only legitimate holders, the latter accept, in principle, the legitimacy of debate on the issue. What distinguishes a democracy is that it always leaves that question open, in keeping with the logic of not recognising any power or authority whose legitimacy cannot be discussed. And at the centre of this discussion, the reflection on those demands that can be qualified or not as human rights remains as a constant.

Albert Camus wrote: “In our daily trials, rebellion plays the same role as the cogito in the realm of thought: it is what’s most obvious. But this obviousness draws the individual out of their solitude. It is a common bond that instills in all men a primal value. I rebel, therefore we are.”3 All human rights are the product of rebellion, and, in this sense, they embody the concerns of all people, forming the common bond among them and forging the solidarity of them all. They are the one thing without which the democratic individual, and thus democracy, could not exist.

The analysis, views and opinions expressed in this section are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policies of the CNRS.

- 1. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-11-15/the-scary-history-of-...

- 2. Claude Lefort, Droits de L’homme et Politique, in Libre 7, Payot, 1980.

- 3. Albert Camus, The Rebel, French edition by La Pléiade, 2008, p. 79.