You are here

Inhibition Enhances Reading Skills

Reading dates back to less than 10,000 years, making it a recent adaptation when compared to the millions of years it took the human brain to evolve.

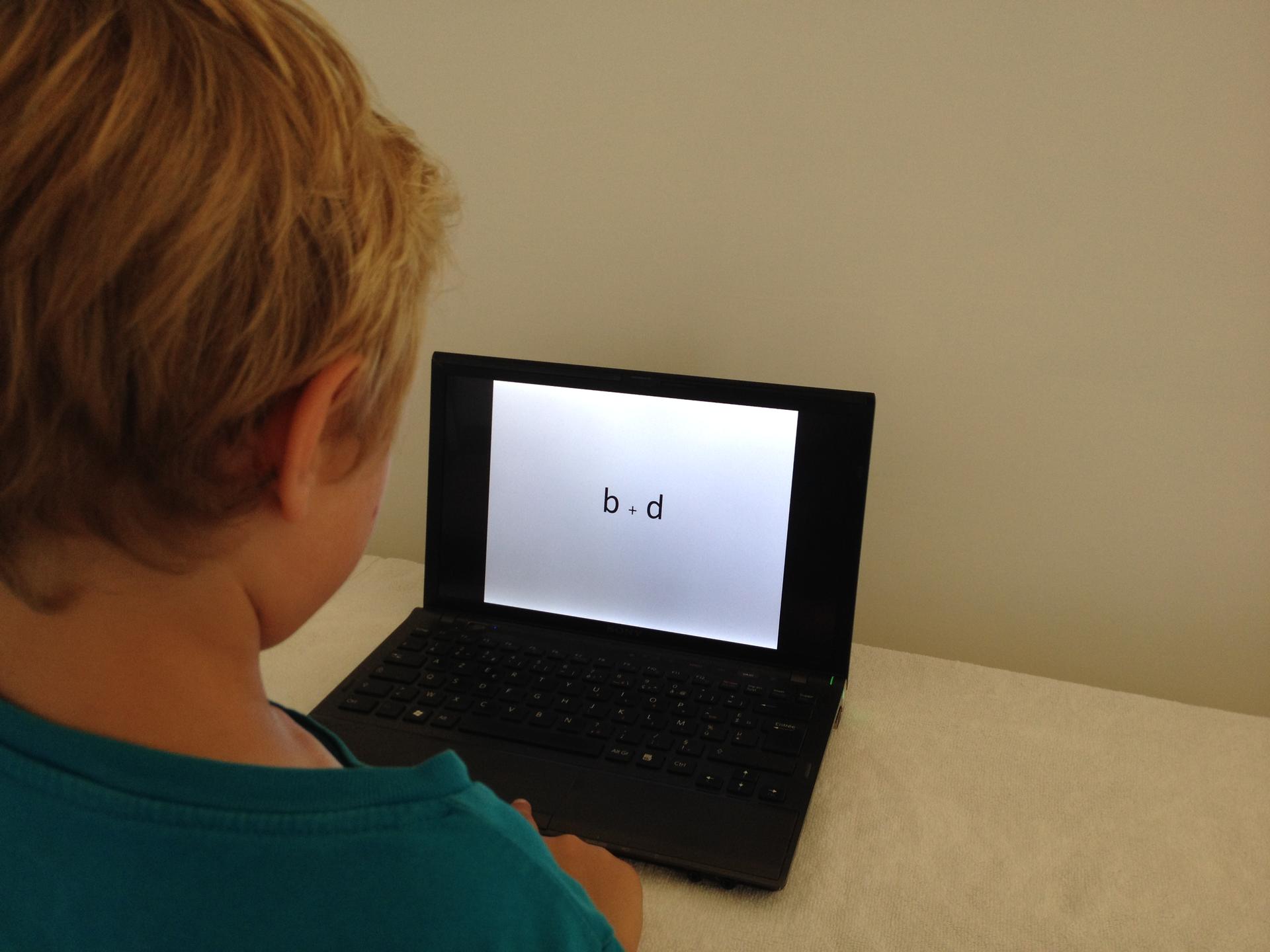

Cerebral imagery has shown that the recognition of letters and animals activates the same parts of the cortex. Based on this observation, neurobiologists like Stanislas Dehaene1 have hypothesized that the ability to read stems from a kind of "biological trick:” the recycling of an ancient cognitive mechanism dedicated to the rapid identification of objects in the environment. “We know that children learning to read confuse mirror-image letters, like b/d and p/q,” notes Grégoire Borst, a researcher at the LaPsyDÉ.2 This is due to the fact that the letter recognition process “repurposes” the neural circuitry that our distant ancestors used to rapidly detect the presence of threatening animals. While this strategy, called mirror generalization, was useful for spotting danger coming from any direction, e.g., a prowling tiger, it induces errors in differentiating words like “big” and “dig.”

Inhibiting the mirror-generalization process

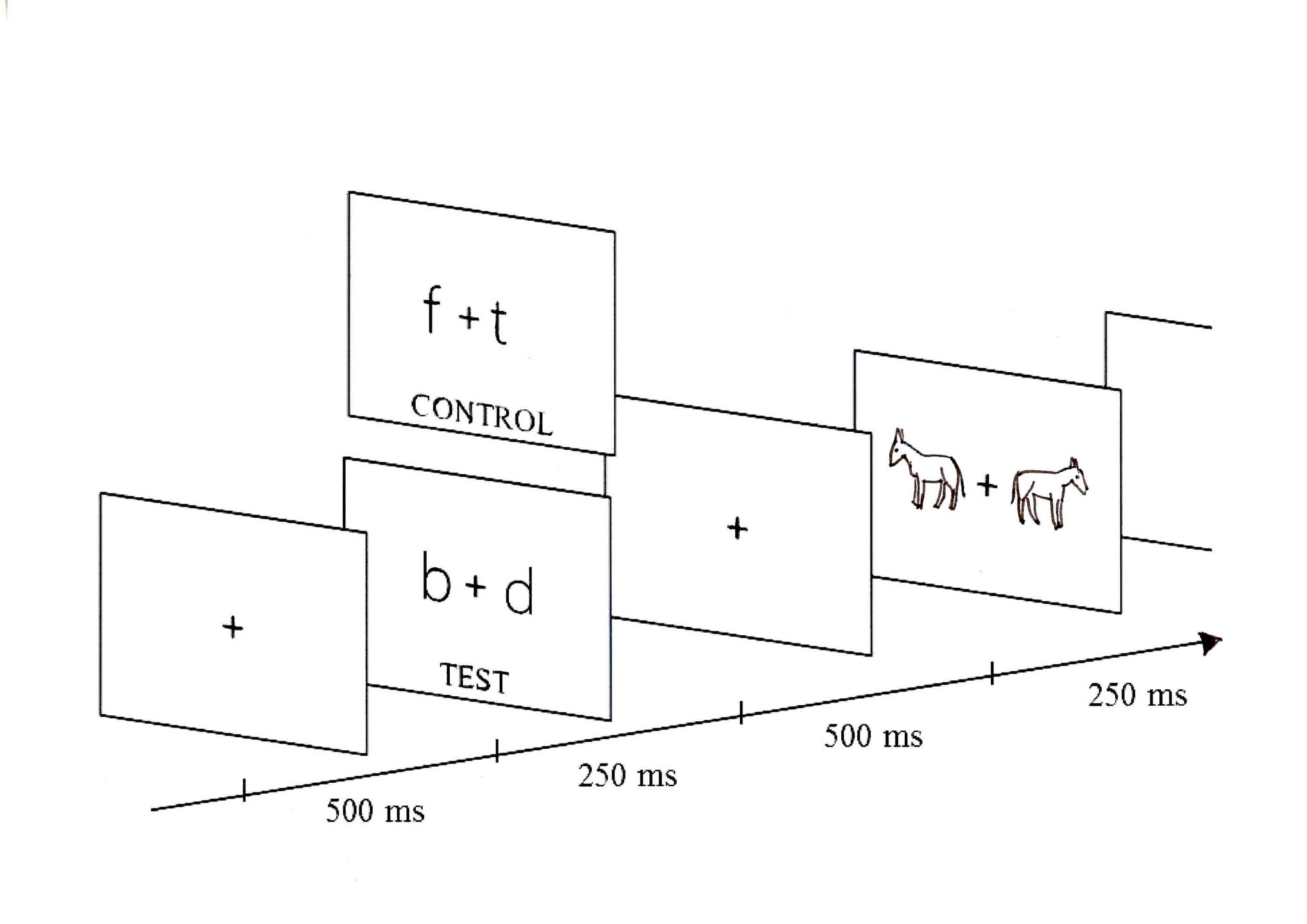

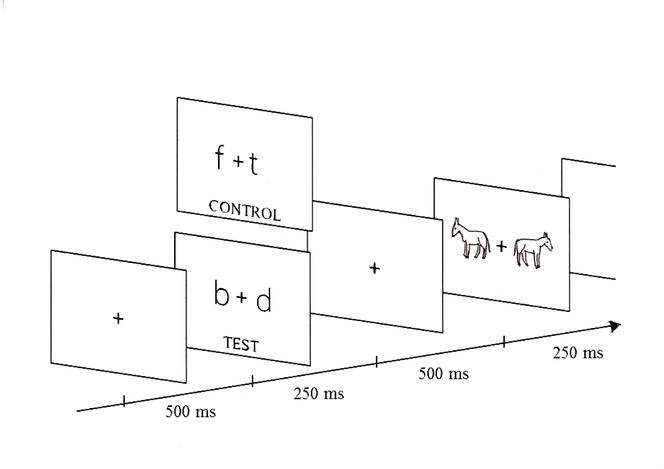

To study the phenomenon, LaPsyDÉ researchers asked 79 students to differentiate pairs of letters and then pairs of images on a computer screen. The results3 confirmed that these experienced adult readers needed more time to distinguish mirror-image than non-symmetrical letters. More importantly, participants took longer to determine that two animal images were indeed identical when preceded by mirror-image letters.

This increase in response time is called the negative priming effect. To distinguish symmetrical letters, the readers must inhibit the mirror generalization process. Yet when this process becomes useful again to identify images of animals, it takes more time to reactivate it.

A weapon against dyslexia

A theory developed by LaPsyDé director Olivier Houdé, who co-authored the study with Borst, postulates that our brains rely on three systems for analyzing our environment. “One is fast, automatic, and intuitive,” Houdé explains in his book on the subject.4 “The second is slow, logical, and thoughtful, while the third is used to decide, on a case by case basis, which of the first two should take precedence. In children, the first two systems develop in parallel, but the third and its inhibitive capacity come later.” Processes like learning to read thus rely in part on the acquisition of an essential cerebral function: the ability to resist psychological automatisms when reasoning becomes necessary.

The researchers believe that children learning to read must be able to inhibit the mirror generalization process, and that some forms of dyslexia could thus result from a deficiency in cognitive inhibition. Should this hypothesis be confirmed, new pedagogical methods could be implemented for helping dyslexic children. Borst suggests two possible approaches: “The first is to correct each and every mistake, teaching the pupil how not to fall into the trap. The second is more innovative and consists in triggering the process that inhibits the mechanisms inherited from neural recycling.” This second approach is entirely novel as the training exercises do not necessarily involve reading and will benefit other skill sets, since this type of inhibition is a general cognitive capacity used in a wide variety of intellectual tasks.

- 1. Neuroimagerie cognitive (INSERM / CEA).

- 2. Laboratoire de psychologie du développement et de l’éducation de l’enfant (CNRS / Université Paris-V/ Université de Caen Basse-Normandie).

- 3. G. Borst et al., “The cost of blocking the mirror generalization process in reading: evidence for the role of inhibitory control in discriminating letters with lateral mirror-image counterparts,” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 2014. doi: 10.3758/s13423-014-0663-9.

- 4. Olivier Houdé, Apprendre à Résister (Paris: Le Pommier, 2014).