You are here

The mysteries of the Cosquer cave

The discovery of the Cosquer cave is a whole story of its own. What were the key events along the way?

Cyril Montoya:1 The discovery was a bit of a bumpy ride for those who took part, largely due to the fact that the site is extremely difficult to access. Although it was found by the diver Henri Cosquer in the mid-1980s, its existence wasn't made public until 1991, following a tragedy in which three divers died in the tunnel leading to the cavern. The Cosquer cave is located beneath the Massif des Calanques and dates back to the Upper Palaeolithic, as shown by the first carbon-14 dating carried out on charcoal samples. However, it was first authenticated by an expert on the Neolithic called Jean Courtin, as it proved impossible to find an archaeologist specialising in the Palaeolithic capable of diving to a depth of 37 metres and swimming along a dark, relatively narrow passageway.

Although France is the country with the largest number of decorated caves in the world, none had ever been discovered east of the Rhône river, in the southeastern region of Provence, which for several months led prehistorians to question its authenticity. However, once these doubts had been dispelled, several excavation and conservation campaigns were carried out in 1992 and 1994, with the participation of Jean Clottes, a prehistorian and cave art specialist. Other experts followed suit.2 The reconstruction of the cave, more than thirty years after its discovery, marks the end of a cycle but not of new discoveries. The site certainly still has surprises in store for us.

During which prehistoric periods was the cave visited?

C. M.: Dating has been performed on some forty samples of charcoal residues collected at the Cosquer site, undoubtedly making it – together with Chauvet – one of the most thoroughly dated decorated caves in the world. It was regularly visited for several thousand years, over a period ranging from 27,000 to 14,000 BC.

This long timespan corresponds to two important Palaeolithic cultures identified by prehistorians, the Gravettian and the Epigravettian. The men, women and children whose handprints have been found in the cave were Homo sapiens sapiens, in other words, they were identical to modern humans in every way. It should be borne in mind that people in the prehistory never lived deep inside caves but rather near the cave mouth, under shelter, or in the open air.

What kind of environment and landscape did they live in?

C. M.: The entrance to the Cosquer cave is today underwater, which wasn't the case 30,000 years ago. At that time, sea level was 120-130 metres lower than today, and the cave was located some six to ten kilometres from the shore. So, strictly speaking, Cosquer is not a coastal cave, even though there are images of marine animals, such as monk seals and great auks. Around the cave there would have been very open, steppe-like countryside, with the rugged Massif des Calanques towering over a wide plain dotted with clumps of shrubs such as juniper, and hills and valleys outlined by Scots pines, a tree species whose charcoal has been identified as having been used both for lighting the cave and as a component of the black paint plastered on the walls. The climate was like that of Iceland today, with short summers and very harsh winters, which explains the presence of some of the animal species depicted.

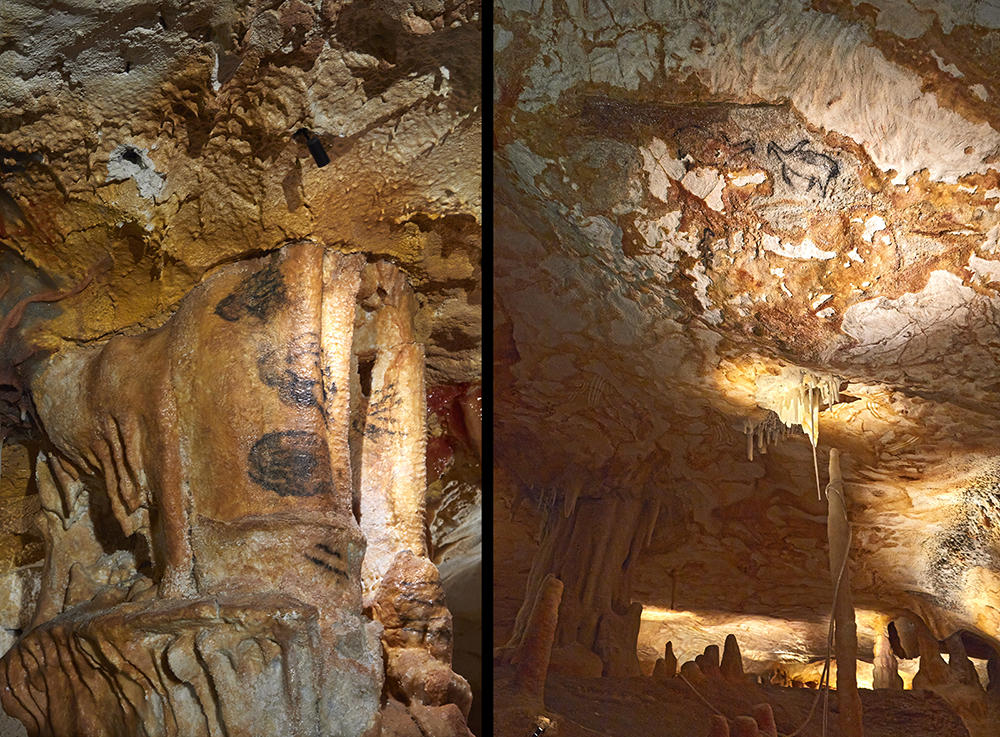

Talking of which, the walls of the cave, featuring twelve different species and over 230 animal figures, display tremendous diversity.

C. M.: Well, a relatively limited diversity in fact, since the main species found there are the same as those in other prehistoric caves, including horses, bovids such as bison, deer, ibex and chamois. Horses are present in large numbers and appear to be Przewalski's horses, which are stocky and short at the withers. However, the Cosquer cave also contains some very unusual features, such as marine animals (auks and seals) and saiga antelopes, a critically endangered species that today lives in the steppes of Central Asia, for example in Kazakhstan. Among the deer depicted is a megaloceros, a very spectacular mammal with antlers spanning as much as three metres. Not to mention animals that haven't yet been identified. Several of the species, such as felines, great auks, saiga antelopes and bison, have today completely disappeared from the Mediterranean region.

Prehistoric artists drew and painted animals but never humans, apart from their hands. From this point of view, the Cosquer cave is no exception.

C. M.: This is indeed one of the many mysteries of cave art, although it isn't entirely accurate. Let's just say that representations of humans are very rare. In the Cosquer cave, there is one possible example, an engraving called ‘The Killed Man’, a human-like figure with a head similar to that of a seal. Besides, archaeologists have found human faces on engraved slabs at the La Marche cave in central western France, which also date from the Upper Palaeolithic. And then you have the Venus figurines of the Gravettian, which are depictions of female humans.

The presence of numerous hand stencils is intriguing. What is their significance?

C. M.: We have indeed identified a considerable number of them. The artist would place their hand on the wall and blow clay all around it, just as you would with a stencil, thus leaving a negative image of it. Hence the term ‘hand stencil’. The hands belonged to men, women and children, showing that entire groups of humans visited the Cosquer cave. This isn't really surprising when you think about the sheer logistics and organisation required to reach the cave and produce the paintings: many people were needed! But that's certainly not the sole reason, as Cosquer isn't the only site that features hand stencils. In fact, this appears to be a pattern that is specific to the Gravettian culture in Europe. The Gargas cave in the Hautes-Pyrénées, for instance, has several hundred of them, as do Pech Merle in the Lot (both in southwestern France) and Chauvet in the Ardèche (central southern France). At Cosquer, some of the fingers on the hands are incomplete, with missing phalanges. The hands may have been mutilated or injured, but the most plausible hypothesis is that they represented a kind of code, a language of communication between hunter-gatherers, like that used not so long ago by the indigenous peoples of North America. But to be honest, the meaning of these signs or codes is no longer accessible to us today.

What did the cave represent? What was it used for?

C. M.: It is highly likely that the cave had several different purposes over the very lengthy period of time during which it was visited. Was it a place of ritual? Or a site where prehistoric men and women recounted and performed myths? What is the significance of the geometric designs that cover certain walls, an oddity that isn't specific to Cosquer? When studying prehistory, you need to be extremely humble, because there are many things that escape us. Which shouldn’t keep us from attempting to unearth the facts.

As an archaeologist, you believe that the Cosquer cave is far from having given up all its secrets.

C. M.: Over the past few years, in order to ensure the virtual conservation of the paintings and engravings in the cave and make them accessible to the public, it was deemed necessary to build a replica of the site by modelling many of its walls in 3D. This makes it possible to showcase the remarkable work that has been completed and ensure that as many people as possible can discover this exceptional heritage. Over the coming years, we will be able to focus on conserving this endangered site through scientific study, since we only have an overview of it. Now we really need to delve into the details. There's a lot more to the cave than the painted walls, which are of course the most spectacular feature. There are also the floors, fireplaces for lighting, and traces of activity of all kinds. For example, we have identified numerous samples of a soft, creamy material produced by the alteration of the limestone walls. What did prehistoric human groups use this calcareous paste for? We are also going to investigate the flint tools discovered in the cave and try to find out what their purpose was.

Has this become a race against time?

C. M.: Yes, the cave is in imminent danger due to sea level rise, and it's only a matter of time before it disappears. 4/5th of it is already under water. We are therefore going to establish a working strategy that will take into account rising sea levels. We now have data going back some fifteen years which shows that this process is speeding up. The damage caused by global warming can easily be seen in the cave. The archaeological excavation campaign we are about to undertake will of necessity be different from the approach used in other decorated caves, where conservation is given priority over all other considerations. Cosquer can only be saved through scientific study, even if this means using invasive procedures that we would no doubt avoid at other sites. In any case, if we don't take action quickly, the sea will soon take care of everything!

What are the key questions the next campaign will attempt to answer?

C. M.: One of the first questions concerns the time period over which the cave was visited. How well-defined is it? I think we can get something more precise. We can't rule out the possibility that there are older remains in the cave. We are going to look more closely at the different periods during which it was used, starting with the hypothesis that the passageway that leads to it today may not have been accessible all the time. Understanding this accessibility is essential, which is why we're going to combine archaeological and geomorphological approaches. The team I have assembled therefore includes karstologists who will enlighten us on how the cave formed in the Massif des Calanques and how it has changed up to the present day, as well as hydrogeologists who can work out the complex functioning of the cave, both now and in the past. Data from the surveys carried out over the past ten years can provide us with a scientific analysis of the ways in which water levels in the cave have risen and fallen.

Our team also includes geomorphologists who will study the sedimentary processes at work inside and outside the cave, and how these two spaces are connected. In addition to this wide range of disciplines, there will of course also be archaeologists who will focus on the floors of the cave, specialists in cave art, and zooarchaeologists who will be able to use the 3D models to study animal behaviour as recorded by prehistoric artists. And this interdisciplinary team is expected to expand, especially concerning palaeo-environmental issues. This genuinely cross-disciplinary investigation will be carried out with the backing of the French Ministry of Culture and the support of local scientific organisations, including the LAMPEA3 and CEREGE4 laboratories.

The reconstruction of the cave is a sort of celebration of digital technologies. Are they transforming your job?

C. M.: Digital technologies enable us to make 3D models with unprecedented detail, on sub-millimetre scales. The models also provide us with information about the order in which the lines were drawn, the stratigraphy, the shape of the tools used, and the precise hand movements of the people who painted or engraved the walls. They also enable us to stay dry and work in comfort, since getting into the cave continues to be an extremely tiring and difficult job. 3D makes it possible to carry out very accurate modelling in the field, and as such provides us with excellent scientific records. However, it remains a tool. Nothing will ever replace the human eye, which can perceive an object in its entirety, and sometimes even spot details that elude technology.

Futher materials:

Discover the Cosquer Cave: Cosquer Méditerranée: the site of the replica of the Cosquer Cave, Villa Méditerranée, Marseille, opened in June 2022.

To find out more: La grotte Cosquer - Un chef-d'oeuvre en péril (The Cosquer Cave - an Endangered Masterpiece), a documentary (in French) directed by Marie Thiry, produced by Gédéon Programmes in co-production with the CNRS. Can be viewed on arte.tv since 4 June.

- 1. Chief curator of Heritage, permanent member of the LAMPEA Mediterranean laboratory for prehistory in Europe and Africa, (CNRS / Aix-Marseille Université / French Ministry of Culture), and scientific director of the Cosquer cave.

- 2. From 1995 to 2000, technical and scientific work was undertaken in the cave under the supervision of the archaeologist Luc Vanrell. In 2002 and 2003, Jean Courtin and Vanrell conducted several campaigns in the cave and completed an initial inventory. Between 200 and 300 graphic features were listed at that time out of the approximately 530 that we know of today. This latest assessment is the result of the work carried out by Vanrell and Michel Olive since 2005.

- 3. Laboratoire Méditerranéen de Préhistoire Europe Afrique (CNRS / Aix-Marseille Université / French Ministry of Culture).

- 4. Centre Européen de Recherche et d’Enseignement de Géosciences de l’Environnement (CNRS / Aix-Marseille Université / IRD / INRAE).

Explore more

Author

Brigitte Perucca is a former director of communications of the CNRS.