You are here

Sustainable cities to fight climate change

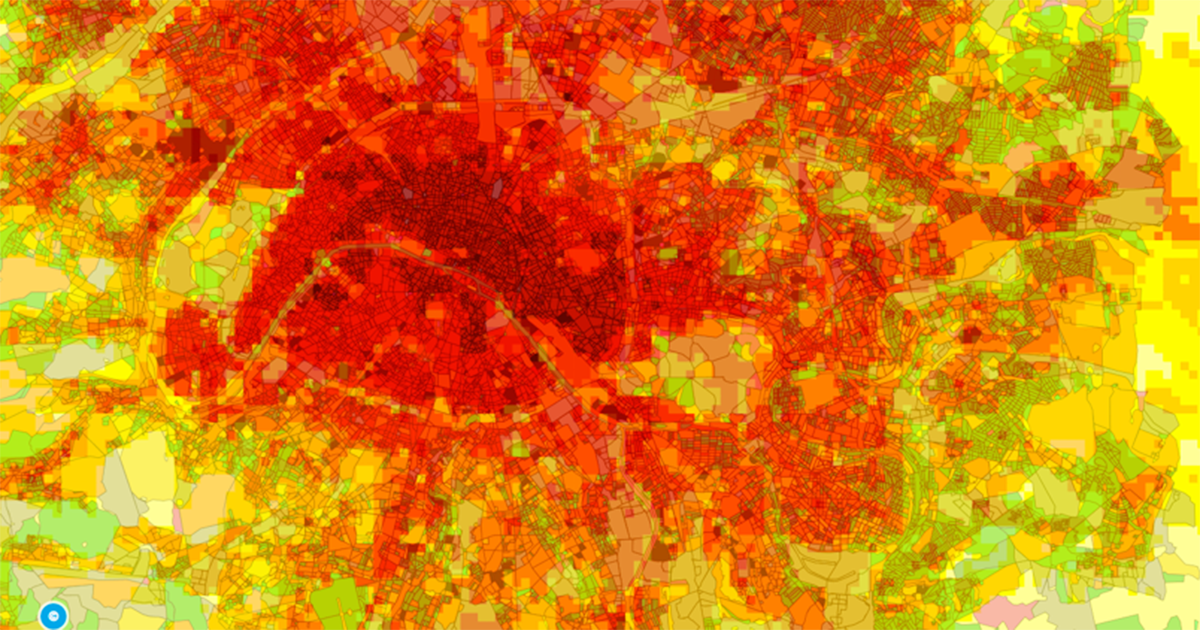

Although cities account for only 4% of the total surface of the European Union, they are home to 75% of its population and produce 70% of CO2 emissions. The Horizon Europe programme is looking to smart cities to curb these emissions. What does this entail?

Christophe Ménézo:1 As head of one of the programmes of Sinergie,2 the French-Singaporean international network on renewable energies with particular focus on smart cities, I know the subject well. These cities, of which Singapore is a prime example, benefit from technological advances in construction, transport, resource management, and recycling. Such a complex system however needs to analyse data provided by a network of sensors constantly measuring different industrial, energy, environmental and social parameters. This analysis involves fields such as material science and energy decarbonisation, economics, law, psychology, philosophy, history, and geography.

Our aim is to achieve Horizon Europe's ambitious goals, and to do so we need to follow a course in line with the targets set. The data is essential for making diagnostics, modelling different scenarios, and adjusting trajectories. We need to acquire and store as much relevant information as possible on cities, neighbourhoods, and buildings, and then analyse it to make projections regarding energy, transport, pollution, and water among others. Shared and open European databases are needed to achieve sufficient resilience in the face of climate and geopolitical disruption. With near-real-time processing, we could almost run our cities like systems using advanced technologies.

And beyond smart cities?

C. M.: Although digital technologies, such as artificial intelligence, present interesting possibilities for cities as technologically developed as Singapore, there is still a need to look at our collective intelligence.

The living world is full of examples of organising which we are studying in collaboration with biologists. Inside anthills for example, blind workers build huge towers from bio-based materials, inside which gases, temperature and humidity are controlled in order to grow mushrooms. It is worth noting that, although cities account for 80% of the world's GDP through their service, trade and finance sectors, they produce almost no resources and live on external support. We are therefore working on bio-inspired urban planning strategies that promote access to resources and enhance local potential. But decisions taken in the short term will only become effective in the medium or long term, which can be seen as a weakness when dealing with the acceleration and magnitude of climate change.

You head the CNRS FédEsol solar energy research federation. What challenges do cities face?

C. M.: I am working on the use of different solar technologies in dwellings and in our cities to provide local solutions where energy needs are concentrated. In urban areas the main challenge with solar energy is the variability caused by the shadows cast by buildings and the areas of fluctuating light throughout the day. The sun's rays are also affected by clouds and haze and the contamination of collectors by pollution, or by temperature levels that exceed those in the countryside due to urban heat islands. There are still many challenges to overcome.

Are other avenues being considered to encourage the move towards climate-neutral cities?

C. M.: Today’s human population growth means that 60% of the buildings we will need by 2050 have yet to be erected, which leaves plenty of room to transform our cities in a positive way. This opportunity, however, will be of little use in achieving targets over the next decade. Indeed, urban development requires to intervene very early on, with most building projects already underway or previously been defined. Action is needed now on urban planning, which is currently based on an aesthetic concept where buildings within a neighbourhood follow regular and orderly layouts and heights. Yet just like in the natural world, diversity plays a key role. It limits the effects of urban heat islands by allowing better ventilation of neighbourhoods and improves access to solar resources.

While cities play a huge role in climate change, they are also particularly exposed to its effects. The increasing use of air conditioning could quickly lead to a vicious cycle where manmade emissions will rise and worsen the effects on the climate. Moreover, both humans and the ecosystem suffer from the combined effects of solar rays, temperature, and pollution, which cause discomfort and health issues, increasing their vulnerability to climate change. Significant challenges lie ahead.

- 1. A university professor, he also runs the Environmental Design and Engineering Optimization Laboratory (LOCIE – CNRS / Université Savoie Mont-Blanc).

- 2. French-Singaporean Network on Renewable Energies, run jointly by the Processes, Materials and Solar Energy Laboratory (PROMES – CNRS) and Nanyang Technological University in Singapore.

Explore more

Author

A graduate from the School of Journalism in Lille, Martin Koppe has worked for a number of publications including Dossiers d’archéologie, Science et Vie Junior and La Recherche, as well the website Maxisciences.com. He also holds degrees in art history, archaeometry, and epistemology.