You are here

Flowers Are not Window-Dressing

"How do you want me to talk about flowers," wrote Louis Aragon in his resistance poem written in the middle of 1943. "I am writing in a country devastated by the plague." A supreme luxury in moments of occupation, times of peace are better suited to the superficial activity of discussing flowers or trying to understand them, as many researchers do, including those in my team.1

For your average person, flowers signal the coming of spring, with its procession of bright trees and colourful prairies. They are also bouquets of roses that come from Ecuador, after a long journey with a high carbon footprint. Or flowers produced in the Netherlands in greenhouses that twinkle, on frigid mornings, like an illuminated checkerboard fuelled by heating and lights. So flowers are a luxury even in times of peace, and a war on climate change at all times?

This would entail forgetting that flowers are not limited to their ornamental function. They are also directly connected to the formation of the fruits and grains that feed us. Some are dazzling, such as the cherry tree or rapeseed, others are more discreet, such as wheat and corn. Yet more generally, the leaves, stems, tubers, and roots that humans and livestock consume almost all come from "flowering" plants.

Today this group actually contains the majority of species (over 90% of the 400,000 identified species of plants). They are much more numerous than mosses, ferns, or gymnospermsFermerPlants whose ovules are "naked" (in other words not enclosed within an ovary), and fertilized directly by pollen. This is notably the case for conifers and Ginkgo., plants from older families that had not yet acquired flowers–that devilishly effective innovation for reproduction.

Studying flowering plants and how they reproduce, as well as understanding their past and anticipating their future, is a highly relevant research subject. We seek to understand what the first flower looked like, the one that gave rise to all the others, from the giant flower of the titan arum to the small flower of the forget-me-not. An international team led by Hervé Sauquet from the laboratoire Écologie, systématique et évolution2 recently created a profile for it, with petals arranged in a crown around a bisexual flower, even though it was often imagined as a male or female with petals in a spiral. In 2017, the team of Jérôme Salse from the laboratoire Génétique, diversité, écophysiologie des céréales in Clermont-Ferrand provided its molecular portrait by predicting the content of its chromosomes and the date of its appearance, a debated question that remains unresolved in the community.

A 174 million-year-old ancestor?

Until now, it was thought that flowering plants appeared approximately 130 million years ago, or the age of the oldest fossils, which left Charles Darwin, the father of the theory of evolution, stunned. A birth around this date would actually entail a highly rapid diversification, with the appearance of large classes of flowering plants in just a few dozen million years. Jérôme Salse's study, along with others published in 2018 and 2019 (in New Phytologist and Nature Plants), predict a much older origin, possibly 200 million years ago, although nothing confirms this.

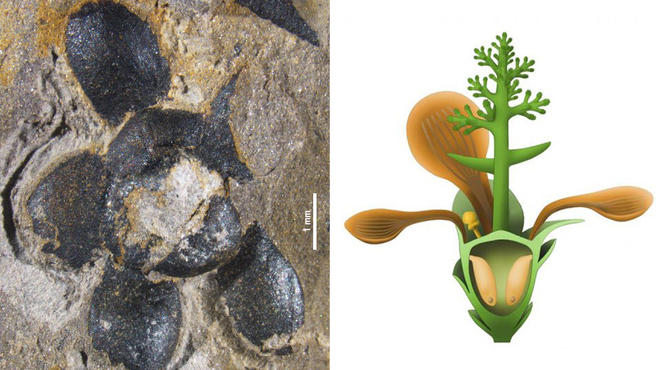

Then in the fall of 2018 came a spectacular turn of events as Chinese and Spanish scientists discovered Nanjinganthus, a relatively well-preserved plant fossil that possesses original structures, some of which are characteristic of flowers, except that they date back 174 million years! If these fossils are indeed flowering plants, the birth of flowers just jumped 50 million years backward. They apparently had much more time to diversify, a discovery that would have spared Darwin many headaches.

The past is becoming clearer, but research is also revealing the secrets of today's flowering plants. We have understood how roses synthesize their fragrance, how pollinating insects learn to recognize heat patterns on flowers (not just colours and fragrances), and how the small grooves on petals form a blue halo without using coloured pigment. An article being reviewed by the scientific community even suggests that the wing vibrations of insects make flower nectar sweeter! Baudelaire's language of flowers and silent things has gradually been deciphered by fundamental research that, after examining a few model species such as the small weed Arabidopsis, is now expanding to numerous species with original properties.

Forced adaptation

Yet studying flowers also involves anticipating the challenges that will emerge if we are unable to contain climate change, or with the disappearance of insects. Plants are extremely sensitive to temperature, whether it is exposure to cold during winter (which influences the flowering of numerous plants during the spring), or the effects of the surrounding temperature, as gardeners well know. It is plausible that our agriculture will need plants adapted to new climate conditions. As this was originally done by our ancestors through trial and error, we will have to redomesticate cultivated plants, but this time by using the mass of accumulated knowledge in this field.

Combined with new technologies, this knowledge will help us adapt the moment of flowering so that harvests remain possible. We already know how to modify the architecture of plants or the size of fruit, as was done over the course of the century with the tomato, although this time starting out from varieties that are naturally resistant to disease. We also recently learned how to propagate, without cross-fertilization, seeds that possess hybrid vigourFermerQuality of plants normally obtained through the crossing of two very different parents, very widely used in agriculture to produce seed.. In the future we will undoubtedly be able to produce plants that will have less need of insects for their pollination.

Far be it from me to replace the struggle against climate change and the decrease of insects by new plants, although I am convinced that we will have to use all possibilities to continue living from our agriculture within a changing context, with greater respect toward both nature and consumers.

Far from being a luxury, the science of flowers and flowering plants promises, in the near future, fruit that is both pleasant and precious.

The points of view, opinions, and analyses published in this column are solely those of the author. They do not represent any position whatsoever taken by the CNRS.