You are here

Imagining the Animals of the Future

In an interview with the Saturday Evening Post on 27 October 1929, Albert Einstein addressed the controversial writer George Sylvester Viereck about his intuitions and inspirations in science: "Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world." For some scientists, this recognition of a certain kind of creativity as the driver of fundamental research is all the harder to accept, coming as it does from such an erudite mind. And yet many mathematicians and physicists have admitted to feeling inspired when they set out their working hypotheses or conjectures, which they then attempt to confirm (or not) using their favorite hypothetico-deductive method.

Ad hoc testing of hypotheses using a reproducible and therefore verifiable technique is one of the characteristics of science. Trying to formulate a problem or hypothesis, sometimes virtually from scratch, can take some form of intuition, if only to overcome writer's block. In this sense, inspiration brings science and art closer together. Paradoxically, some practitioners of the so-called hard sciences readily compare their mathematical formulas and equations to a musical score. But can imagination also be of use in the life sciences, and if so, to what end?

Using the imagination to understand reality

In 1962, the eminent zoologists Gerolf Steiner, under the pseudonym Harald Stümpke, and Pierre-Paul Grassé, who signed the preface, wrote "The Snouters: Form and Life of the Rhinogrades," a stimulating book providing an extremely rigorous and academic account of a fictitious group of mammals characterized by a prominent nose-like feature, hence their common name, "snouters." As well as being a hoax (as Grassé warns: "biologist, my friend, remember that the best described facts are not always the truest"), this provocative book laid the foundations of what is known today as speculative biology.

Speculative biology is an intellectual exercise that aims to imagine plausible life forms, either elsewhere in the Universe, or on a future Earth (it is then called speculative evolution). Although such speculation needs to be rigorous and take into account genuine data (such as that relating to natural selection), once turned into a fictionalized account, it simply becomes a work of science fiction. Since speculative biology does not claim to be a science, it cannot be considered as a pseudo-science.

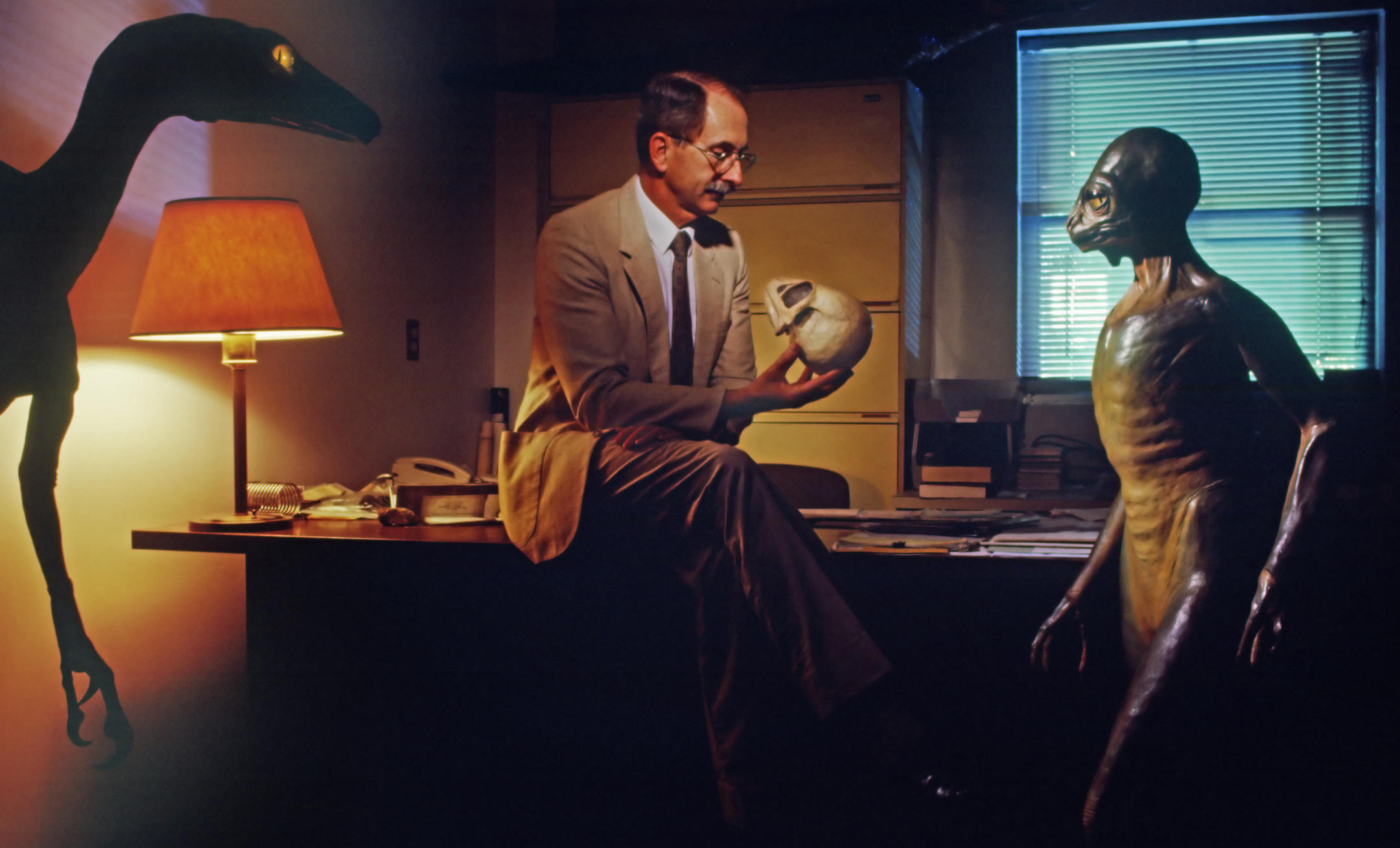

It is worth pointing out that, when fiction consists in rewriting the history of life (in which case it often begins with "What if...?"), speculative biology becomes alternative history, another genre of science fiction that has become fashionable in recent decades: in 1981, the Canadian paleontologist D.A. Russell made a detailed description of a new bipedal dinosaur better known today under the name Troodon. Intrigued by the large size of its braincase, Russell and his taxidermist colleague R. Seguin imagined an intelligent dinosaur in a counterfactual scenario where the species survived the Extinction Event and evolved until the present day.1

From the celebrated fur-bearing trout to the baby dragon skeleton currently on show at the French Natural History Museum's Gallery of Comparative Anatomy, naturalists have frequently resorted to chimeras to comprehend real organisms: classifying species and describing nature to understand it better also means reflecting on the concept of reality. Hoaxes in which the distinction between true and false is blurred are not only fun but can also take on a quasi-philosophical and beneficial role. Speculative biology creates fictitious organisms that shed light on real ones, just as speculative evolution invents chimeras of the future in a bid to explain the present.

Testing models and predicting potential discoveries

Works of speculative biology flourished in the 1980s and 1990s. In his illustrated speculative anthropology,2 the Scottish geologist Dougal Dixon explored the possibilities of the future evolution of humans, some inspired by stereotypes found in the science fiction novels of H.G. Wells, René Barjavel and others.3 Nine years earlier, the same prolific author published "After Man: A Zoology of the Future," where he imagined various forms of life on Earth in 50 million years from now.4 Plate tectonic models as well as considerations about climate change were included in his analysis. Dixon's work was later adapted for a documentary series called "The Future is Wild." While futurology was very popular at the time, a spate of films and series focused on "extraterrestrial" biology: "Alien Planet," another series, made an intelligent attempt to imagine complex and plausible ecosystems on a fictitious Earth-like planet, skilfully guiding the viewer from planetary science to speculative ecology.

The astrophysicist Roland Lehoucq, the protohistorian Jean-Paul Demoule, the writer Pierre Bordage and myself stepped up the exercise when we wrote a speculative story5 in which an extraterrestrial species accidentally becomes intelligent enough to create its own history. This kind of "hard" science fiction, typical of the English-speaking world, which attempts to follow and disseminate current scientific knowledge (in the physical sciences, life sciences, humanities and social sciences, etc), evolves with major advances such as the detection of an ever-increasing number of exoplanets, or, here on Earth, the discovery of live or fossil extremophiles and species with extraordinary, almost "extraterrestrial," morphologies. This evolution also goes hand in hand with the growing awareness that life in the Universe should no longer be considered a miracle but rather as a common phenomenon.

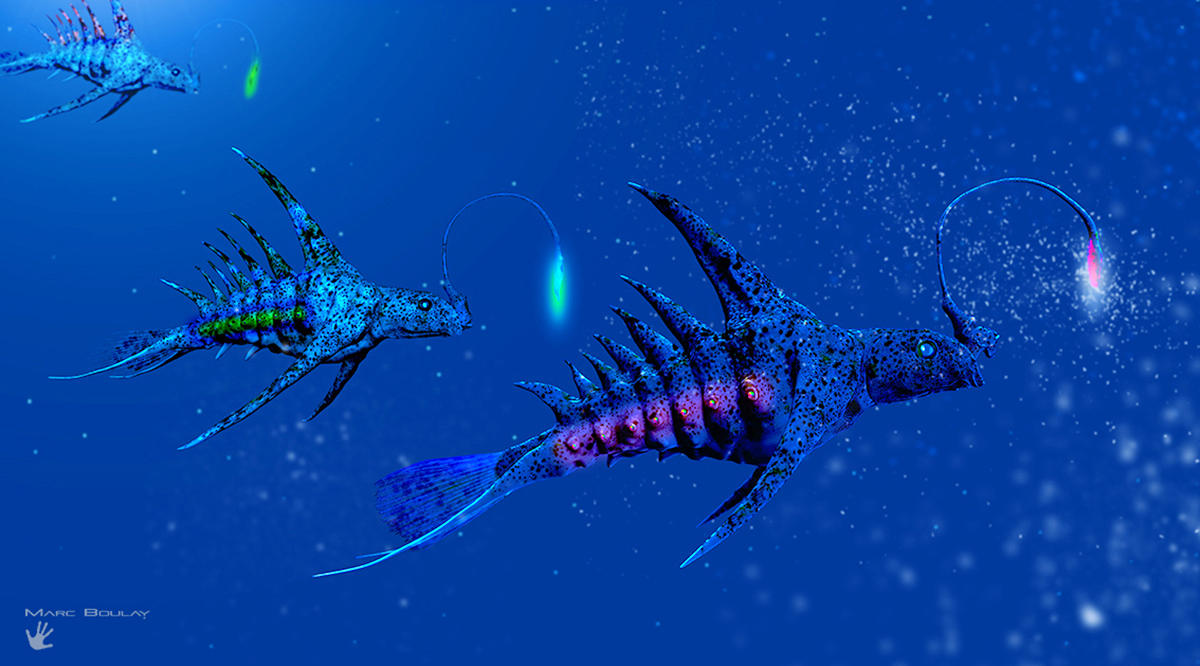

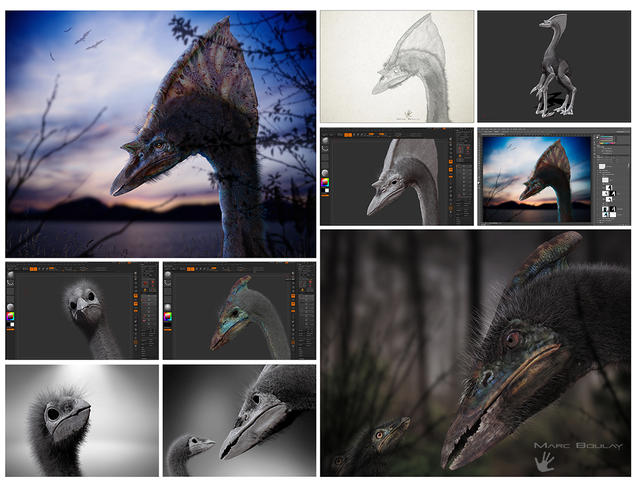

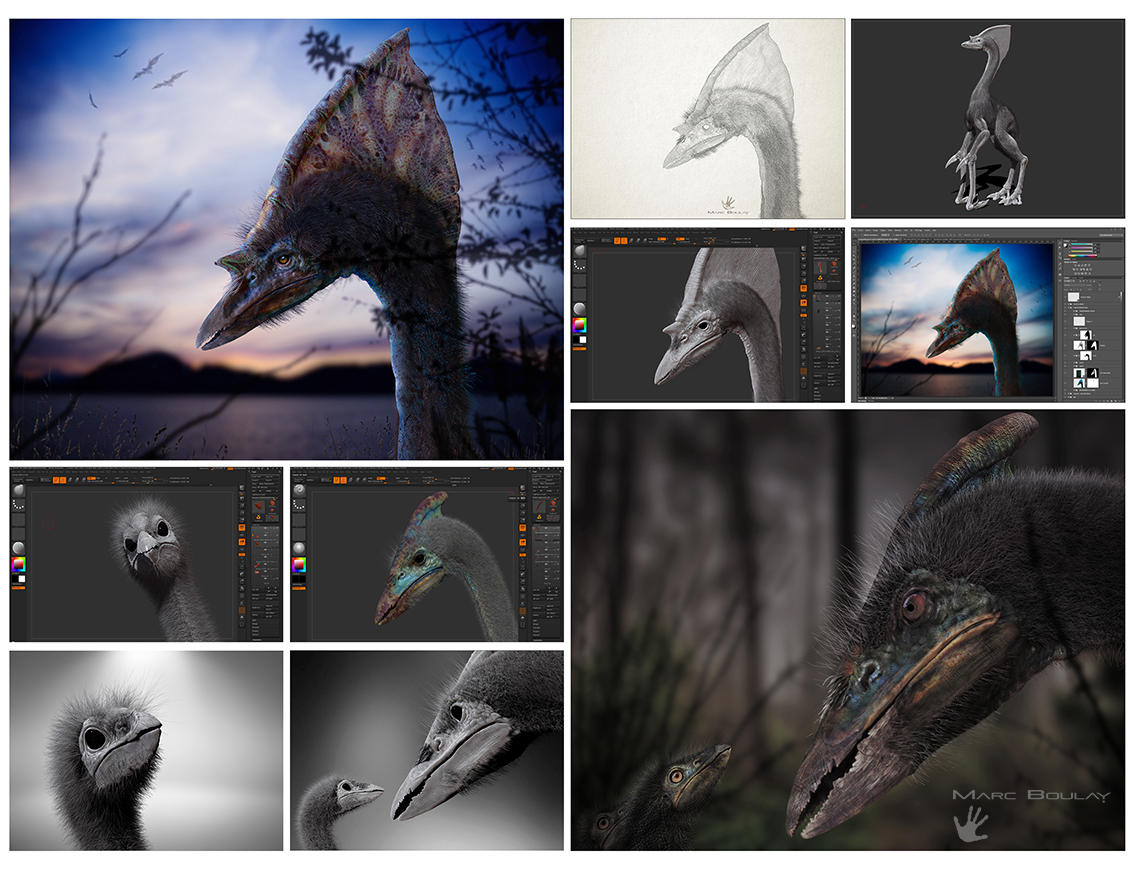

Demain, les Animaux du Futur ('Tomorrow, the Animals of the Future'), published jointly with the sculptor and paleo-artist Marc Boulay, ,is the result of some ten years of collaboration between art and science,6 This book of speculative evolution attempts to imagine life flourishing on Earth in ten million years' time, in the absence of humans. "In addition to the dissemination of knowledge, this exercise enabled us to test biomechanical models and predict potential discoveries: until it was unearthed, who could have imagined the existence of an 'improbable' dinosaur7 exhibiting features both of birds and of bats? As well as being a work of imagination that explores a tiny range among an almost infinite number of fictitious forms, we also wish to invite readers to think about the impact of humans on nature, while reminding them that the evolution of species is not predictable.

Speculative biology can thus play a significant role. But does that make it publishable? In 1982, the description of D.A. Russell and R. Seguin's "reconstruction" of a fictitious dinosaur was published in the same scientific paper as that of the real dinosaur. Would any of today's scientific journals dare take up the challenge?

The analysis, views and opinions expressed in this section are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policies of the CNRS.

- 1. D. A. Russell and R. Seguin, "Reconstruction of the Small Cretaceous Theropod Stenonychosaurus Inequalis and a Hypothetical Dinosauroid," Syllogeus, 1982.

- 2. D. Dixon, "Man after Man: An Anthropology of the Future," St. Martin's Press, 1990.

- 3. L’homme du futur dans la science-fiction, J.-S. Steyer and R. Lehoucq, Pour la science, n° 422, 2012.

- 4. D. Dixon, "After Man: A Zoology of the Future", St Martin's Press, 1981.

- 5. Exquise planète, P. Bordage, J.-P. Demoule, R. Lehoucq and J.-S. Steyer, Odile Jacob, 2014.

- 6. Demain les animaux du futur, M. Boulay and S. Steyer, Belin, 2015.

- 7. Xu et al., "A Bizarre Jurassic Maniraptoran Theropod with Preserved Evidence of Membranous Wings," Nature. 2015(521): 70–73.