You are here

There is indeed a gender bias when evaluating future teachers or professors for certain fields, but it’s not what you think. In a new study,1 based on results from French examinations for teacher accreditation, researchers were able to show that a grading bonus favors women in male-dominated scientific disciplines in France, such as physics and mathematics. The research team’s23analysis of data sets—more than 100,000 exam takers between 2006-2013—also indicates that the evaluation bias increases with the degree of male overrepresentation in a field, and that to a lesser degree, it can even favor men in fields where women are overrepresented, such as literature or foreign languages.

Examining the exams

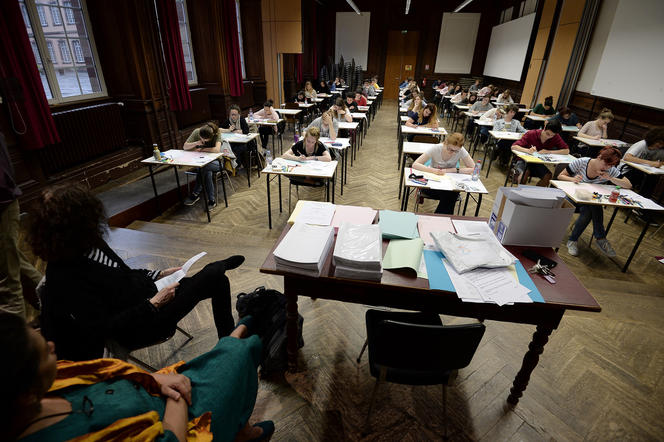

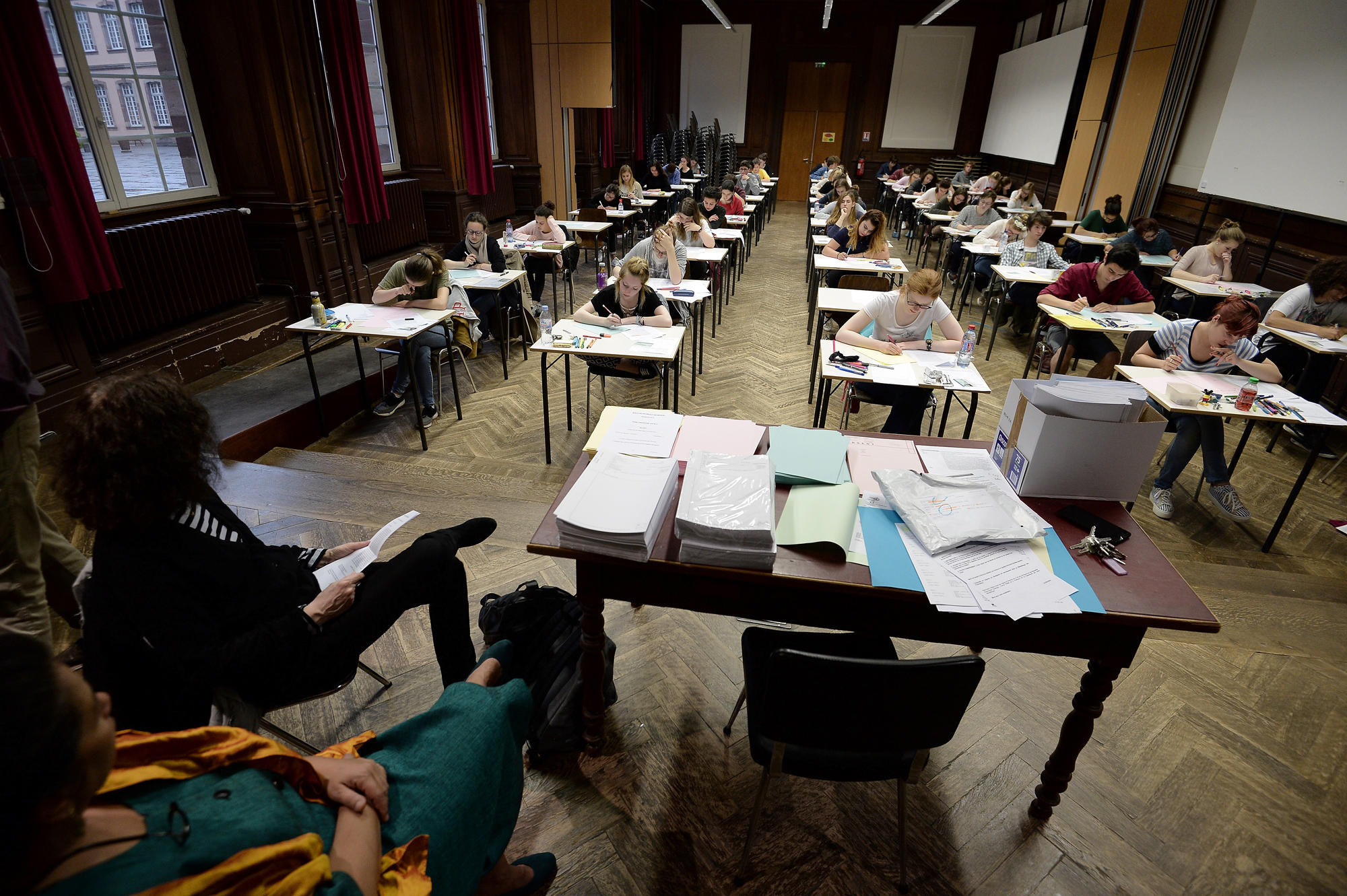

For their study, the researchers included data from France’s three national competitive examinations for teacher accreditation—the CRPE for primary-school teachers, the CAPES for middle school and high-school teachers, and the Agrégation for professors in higher education—which are used to select the vast majority of French teachers and professors.

“We began by conducting statistical comparisons between the first part of the exam, which is written and gender blind, and the second part, which is a non-blind oral examination administered to students scoring above a certain level on the written section,” explains Thomas Breda, who co-authored the study. “Among the 11 academic fields involved, we observed a consistent increase in percentile rank for women between the written and oral sections in most but not all STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), which tend to be male-dominated.”

Gender boost or bust

The largest difference of percentile rank—the rise in ranking women experienced between the written and oral exams—occurred in fields where they were the most underrepresented, with an average jump of 10 percentiles in math, physics, or philosophy, in which women’s share in the field hovers around 20%. This percentile jump has a considerable impact on hiring. For instance in mathematics, where the share of women actually hired was 27.9%, exclusive use of the oral test would have resulted in a somewhat higher fictive hire rate (29.8%), while exclusive use of the written exam would have resulted in a significantly lower fictive hire rate (23.1%). The same dynamic applies to men, who had a jump of about 4 percentile ranks between the written and oral portions of the test in the female-dominated fields of literature and languages, in which men have a share of approximately 40%. In fields with greater gender balance, such as history, geography, and other social sciences, the gender differences in evaluation were minor.

“To ensure that we were interpreting the data correctly, we considered a number of other potential causes,” adds Breda. “For instance, one could argue that women score better because oral exams test more for non-cognitive skills such as elocution, in which women may have a gender advantage over men, or because women drawn to male-dominated fields tend to be more confident in their subject, and thus better-suited to succeed on the oral exams. Yet if this were true, the rise in ranking would appear in all fields, not just male-dominated ones. Moreover, the same ranking differential is seen in the non-subject-specific BERCS4 component of the oral exam, thus excluding confidence in or aptitude for a subject as a causational factor. In short, examiners seem to favor women in male-dominated subjects regardless of what they are tested on.”

Breaking gender stereotypes

This evaluation bias favoring the minority gender increases its chance of being hired, and rebalances gender distribution. Yet if this is true, why does underrepresentation persist? A first answer is that these figures are for secondary education to higher education recruitment, and that unbalancing factors such as subtle pressures or stereotypes may still discourage women from pursuing these fields at earlier stages, before decisions regarding higher education are made.

“These findings could help identify effective policy measures geared toward getting more women into science,” notes Breda. “Non-blind evaluation and hiring processes could help lessen gender imbalance, as could combatting stereotypes and social norms in earlier stages, before educational paths are selected. A recent survey shows that approximately 60% of high school students believe there is a bias against women in male-dominated fields. Informing women that they will not necessarily be subject to discrimination, and on the contrary that they may perhaps even have advantages, is a positive step to dispelling concerns. A way of doing so may be by having female scientists present their career experiences in high schools, thereby serving as role models.”

The study, which was conducted over the past year, is the outgrowth of five years of research on inequalities in the labor market, ranging from subjects such as how employees react to feminization in the workplace to the gender wage gap. In fact, informing female high school students about their opportunities in the field of science can not only reduce gender imbalance, but also help shrink the wage gap by increasing female presence in key economic sectors such as science and industry. These findings are relevant for France but also for other developed countries, which experience the same dynamics of gender imbalance, as shown by preference for women in a recent hiring experiment in the US.5

- 1. T. Breda and M. Hillion, “Teaching accreditation exams reveal grading biases favor women in male-dominated disciplines in France,” Science, 2016. http://doi.org/10.3886/E81536V3

- 2. Paris School of Economics, Paris-Jourdan Sciences Économiques (CNRS / Paris School of Economics).

- 3. Centre de recherche en économie et statistique (CREST).

- 4. The BERCS component (Behave as an ethical and responsible civil servant) was added to the oral exam in 2011 across all fields.

- 5. W.M. Williams, S.J. Ceci, “National hiring experiments reveal 2:1 faculty preference for women on STEM tenure track,” PNAS, 2015. 112:5360-5365.

Keywords

Share this article

Author

Arby Gharibian is a writer, translator, and independent researcher in social sciences, art, and literature .

Comments

Thanks for this article. I

Submitted by biomedstaff on July 30, 2016 at 01:17amLog in, join the CNRS News community