You are here

Urbex, the thrill of urban exploration

You recently published a book on the phenomenon known as urbex. What exactly is it?

Nicolas Offenstadt1: Urbex, or urban exploration, is the in-depth investigation of marginal and abandoned sites, which are generally entered without permission, including closed factories, disused army barracks, former sanatoriums, etc. Its development coincides with a massive abandonment of public and private buildings in connection with two major events in our Western societies: deindustrialisation and the demise of the Eastern bloc. Today urbex is practiced by thousands of people, and fascinates hundreds of thousands more. The large number of Internet sites devoted to this practice speaks for itself. Social media, where the term ‘urbex’ spread starting in the early 2000s, has played a key role in the phenomenon, which entails exchange and sharing. People see it as a genuine movement rather than isolated individual practices.

Why such enthusiasm for urban ruins?

N. O.: There are a number of reasons. The first, which is fairly classic, is a taste for adventure. Entering these abandoned sites is often physically challenging, and even acrobatic. You climb over roofs, go through holes in fences, not to mention ‘The Famous Five’ side of it, as it can be a little frightening. The second reason is photography. Snaps of ruins and forgotten places are very popular, to the point that it has become a genre in itself. The passion for heritage is another explanation. We are experiencing a ‘heritage boom’, which is naturally embodied in this exploration of ruins and disused sites. I see a final motivation, and that is a need for liberty. We live in cities that are increasingly organised and policed, in which such locations are becoming rare, and freedom of movement is extremely constricted. In this highly limiting context, urbex offers a new space of freedom.

Are there hotspots for urbex, locations that absolutely must be visited?

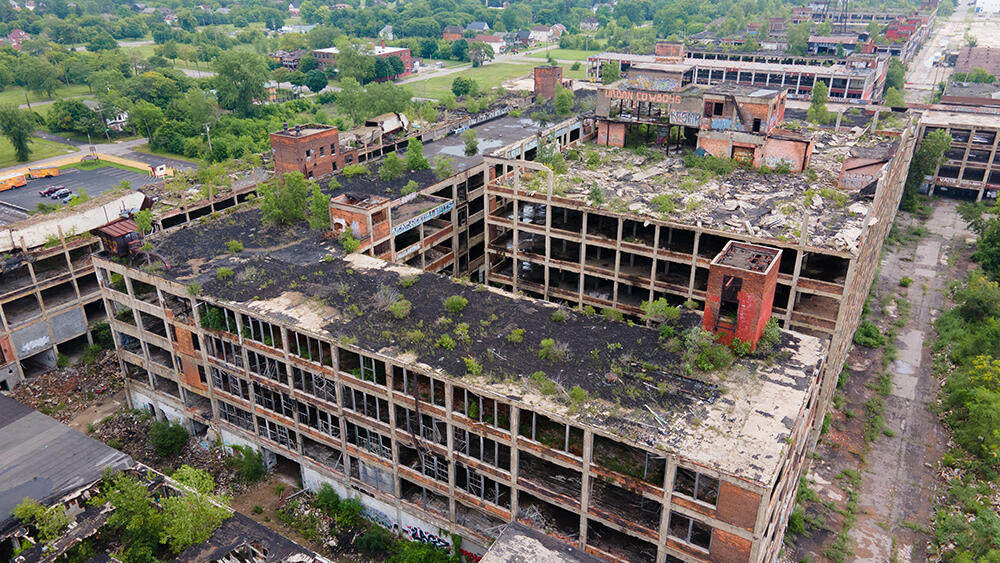

N. O.: Yes, there is a hierarchy, and sites that are particularly emblematic. Until the war in Ukraine, the abandoned Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant was a must. There is also the former headquarters of the Bulgarian Communist Party in Buzludzha, a UFO nestled atop a rocky summit, or the former Beelitz sanatorium (and hospital) in Germany. In the United States, the abandoned factories of Detroit – the erstwhile jewel of the automobile industry – have become icons, such as the Packard Automotive Plant. All of these places have been captured in thousands of videos and photos, and shared on hundreds of dedicated sites.

In France as well, there are ‘spots’ that are easier or better known than others, such as certain châteaux, or shuttered factories. They are often – but not always – located in demographically stagnant areas, where lack of real estate pressure explains why they have not been torn down or rehabilitated.

Who are urbexers?

N. O.: It all depends on their motivation. There are young people looking for adventure, professional photographers specialising in urban ruins, and local heritage enthusiasts, whose approach can be more or less activist. In Amiens (northern France), I met a history teacher, Louis Teyssedou, who turned into a rescuer of his city’s industrial heritage. With his high school students he led an effort in connection with one of the former landmarks of the city, the derelict Cosserat velvet factory, which closed in 2012. This exploration gave rise to a book and exhibitions.

While some men emphasise a virile side of urbex, due to its sportive and risky nature, many women also practice it, sometimes in a slightly different way: they do not go exploring alone as they are more concerned about their safety and potential bad encounters, but they have also developed a whole series of strategies for dealing with them.

Urbex is by definition an unauthorised and often illegal practice. Do rules nevertheless exist?

N. O.: Yes, there is an unofficial urbex code. You do not break and enter, you do not touch or degrade anything, you do not give the address of the site, and you do not take anything. Urbex websites on the Internet do not provide the exact location of the ruins pictured. However, relations of trust can be established, with experienced urbexers sharing tips. Structured global networks have emerged, and meet regularly, which has enabled me to have discussions with multiple members.

My own urbex practice is a little different, in that the heritage and historical aspect is central to me. I combine urbex and more traditional research, with an effort towards documentation. I allow myself to take things.

This is a distinctive characteristic of your research on urbex: you yourself are a historian and an urbexer. How did you come to this practice?

N. O.: I began visiting industrial ruins before urbex existed, especially in the mining areas of northern France in the 1990s, alongside my dissertation on the Hundred Years’ War. I have done a great deal of work on heritage and memory throughout my career, as I am interested in the history of sites. But it was a little over ten years ago that I truly systematised my urbex practice. During a tourist trip to the ex-GDR, I was struck by the number of abandoned facilities. I entered a shuttered brewery in Schwerin out of curiosity, and was surprised by the number of documents that had been left there. I wondered whether it was an exception, or if all these abandoned places were brimming with objects. I ultimately built an entire research project around these sites in the former East Germany.

How many sites have you ‘urbexed’ in the former GDR?

N. O.: I have explored 350 sites: factories, cultural centres, barracks, abandoned workshops – a whole swathe of neglected socialist civilisation. The ethical rule is not to take anything, to be happy with photographing what you find. But these sites are completely derelict, and I admit I have proceeded with unauthorised sampling from the many archives I found during these visits. I take responsibility for my actions: some of these factories and files were destroyed shortly after I was there, with nothing being saved.

For instance, in a factory in Saxony, I found a thick file on the Cuban workers who had worked there, showing the ambiguous ties between East Germany and the Republic of Cuba. I have used some of these documents in my books on the history of the GDR. This has never caused problems, since the locals don’t seem to be interested. All of these buildings and archives are often seen as the material traces of a political and economic failure, as a symptom of an undesired past.

What kind of an urbexer are you?

N. O.: I’m a fairly dynamic urbexer who does not set limits in advance. I climb, I crawl, I enter via air ducts. I believe it’s the only way to discover these sites, within reasonable limits of course, because I’m now over fifty. I often go alone, but over time young historians and work colleagues have also become exploration partners. However, solitary practice is not recommended by certain urbexers, in the event something happens – there are deaths every year. Once, a staircase collapsed, and the person I was with fell five metres.

To avoid problems, I evaluate the risks at each stage of the expedition. And of course I wear protective equipment, including safety shoes – which sometimes do not prevent nails measuring a good centimetre and a half from piercing through the soles – in addition to jeans, a hat, protective gloves, and I make sure to take a large quantity of water in case of a problem or an extended visit, along with a small first-aid kit. One thing is clear, urbex is an activity that should always be well-thought-out. These explorations are dangerous, risky, and quite peculiar. They require self-control, resilience, and a sense of one’s limits.

Why are such places so fascinating, despite the risks?

N. O.: This issue needs further investigating, but we can already say that they are seen as new territories offering new freedoms within a fairly constrained world. This attraction is also in keeping with a powerful return to the past, in the face of a future often seen as more opaque.

These sites finally appear as metaphors for disappearance, and illustrate how nature is seemingly taking revenge against the Anthropocene: revegetation is everywhere, with plants growing on desks, between books. The environmental crisis and soil artificialisation have also led to rethinking abandoned sites and their use, and might eventually give them a new lease of life.

Further reading:

Urbex : le phénomène de l'exploration urbaine décrypté, Nicolas Offenstadt, Albin Michel, March 2022, 192 pages, 14.90 euros.

Urbex RDA : l'Allemagne de l'Est racontée par ses lieux abandonnés, Nicolas Offenstadt, éditions Albin Michel, Sept. 2019, 258 pages, 34.90 euros (digital version 9.99 euros).

- 1. Historian and senior lecturer at Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne.