You are here

Revealing the Amazing Amazon Reef

It turns out that there’s more to French Guiana than its tropical forest, hundreds of species of trees, and abundant fauna. Some hundred kilometres out to sea, there is indeed a region that enjoys astonishing biodiversity: the Amazon reef. “Discovered just a few years ago at the mouth of the River Amazon, the reef extends as far as the coast of French Guiana,” explains Serge Planes, a biologist at the Centre for Island Research and Environmental Observatory (CRIOBE).1 “Lying on the ocean floor, right on the edge of the continental shelf, what must have been a coral reef during the last glacial period is today submerged at a depth exceeding a hundred metres, in total darkness.” Last September, a team of scientists on board the Greenpeace ship Esperanza discovered an amazingly diverse ecosystem, both on the reef itself and at the ocean surface, with large numbers of cetaceans, birds and other animals.

“Although the reef had already been examined by Brazilian researchers off the coast of Brazil, this is the very first time that a team of divers has gone down there to collect biological samples,” the scientist explains. Diving to a depth of 100 metres is already no easy task, but doing so in the waters off French Guiana, renowned for their turbidity caused by sediment from the Amazon and high concentrations of plankton, is an especially tricky operation. “In the top few metres the water is so cloudy that you can’t see anything at all, and below 70 metres hardly any light from the surface gets through,” the biologist adds. Down on the sea floor, marine snow, made up of white flakes produced by decomposing plankton, constantly rains down on the reef.

Islands of biodiversity a hundred metres down

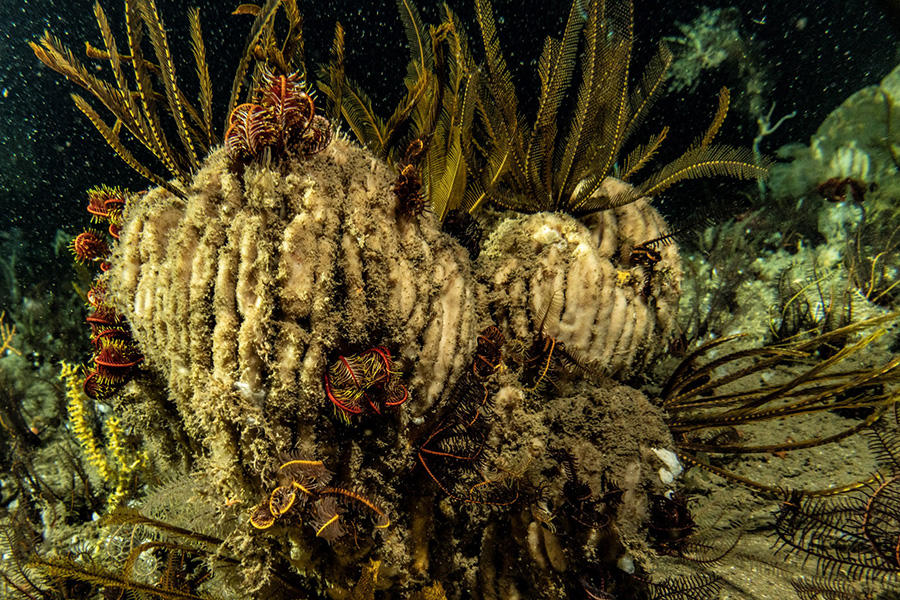

In this strange setting, scientists have discovered a host of invertebrate fauna, dominated by the sea urchin species, including crinoids (primitive shell-less sea urchins), common sea urchins, starfish and brittle stars. In addition, there are populations of more common species, such as gorgonian coral, black coral, fish, molluscs and crustaceans. “The fauna we have observed in the Amazon reef resembles a mix of coastal fauna of the kind found in the coral reefs of the Caribbean, further north, and animals that are more typical of sandy sea beds and abyssal plains,” the researcher adds.

DNA analysis has yet to be carried out on the 2,500 samples collected, with the aim of describing them in detail and identifying the origin and vulnerability of this very special ecosystem. “The Amazon reef isn’t a continuous reef. We’re talking more about islands of biodiversity, which will need to benefit from appropriate conservation measures.” There is no doubt about the need to establish a protection plan for the area, given the economic interests at play in the region: while no projects have yet been launched, the threat of offshore oil rigs being built at the mouth of the Amazon – and with them the risk of oil spills – is very real.

“With ocean currents carrying the Amazon plume northward towards French Guiana and Suriname, any pollution from Brazil would automatically impact the coast of French Guiana and disrupt this highly unusual ecosystem,” explains Olivier Van Canneyt, a biologist at the PELAGIS observatory. This specialist in marine megafauna (cetaceans, sharks, large fish, seabirds, etc), who had already flown over the area in 2008 and 2017, is still amazed by the observations carried out on board the Esperanza.

Fifteen species of cetacean observed

“Contrary to what one might think, warm ocean waters are not particularly favourable to abundant life, with the notable exception of coastal areas such as coral reefs,” the researcher explains. “Which is why we were extremely surprised by the diversity and densities of the animal populations we encountered off French Guiana.” During ten days at sea, the biologists identified around fifteen families of cetaceans, including nine dolphin species: bottlenose, pantropical spotted, and round-headed dolphins as well as Globicephalinae, such as melon-headed whales and pygmy killer whales.

“We were also surprised to see humpback whales with their calves just a few weeks old, and Bryde’s whales in the process of attacking schools of small fish, alongside tuna, sharks and seabirds. We would normally expect to see this kind of abundant life in plankton-rich cold or temperate waters, such as in the Bay of Biscay.” The biologist believes that this exceptional diversity is due to the mixing of sea water with fresh water not only from the Amazon, but also from French Guiana’s ten or so rivers, such as the Oyapock and Maroni, which form its frontiers with, respectively, Brazil and Suriname. “The presence, along the coast of French Guiana, of kilometres of mangrove forest, a habitat that favours the reproduction of many fish species in particular, is bound to foster biodiversity in the open sea.”

One thing is certain: this kind of abundance shows that the ocean off French Guiana, rather than being a mere place of transit for marine animals, fulfils key functions for their survival such as reproduction (humpback whales), and feeding (Bryde’s whales and manta rays, as well as the olive ridley sea turtles that hatch along French Guiana’s coast). Protecting this area should therefore be an utmost priority.

- 1. CNRS / Ecole Pratique des Hautes Études / Université de Perpignan Via Domitia.